Chattel

Learn what chattels are in Canadian real estate, how they differ from fixtures, and why clearly identifying included items is essential in a sale.

Shutterstock

May 22, 2025

What is a Chattel?

In real estate, a chattel refers to any movable personal property that is not permanently attached to the home or land and is not included in the title of the property.

Why Chattels Matter in Real Estate

In Canadian real estate transactions, it's important to distinguish between chattels and fixtures. Chattels are typically excluded from the sale unless explicitly listed in the Agreement of Purchase and Sale.

Examples of chattels include:

- Freestanding appliances (e.g., washers, dryers)

- Furniture

- Portable sheds or storage units

Disputes can arise when buyers assume certain items are included. Clearly identifying chattels in the offer helps avoid confusion or legal conflict after closing.

Understanding chattels ensures buyers and sellers are on the same page regarding what's included with the home.

Example

The buyer expected the stainless steel fridge to stay, but it was a chattel and not listed in the agreement, so the seller took it when moving out.

Key Takeaways

- Movable items not affixed to property.

- Not automatically included in sale.

- Must be listed in purchase agreement.

- Different from fixtures.

- Source of common closing disputes.

Related Terms

- Fixtures

- Agreement of Purchase and Sale

- Inclusions

- Exclusions

- Closing Process

Renderings of the 65-storey tower previously proposed for 145 Wellington Street West. (Turner Fleischer / SKYGRiD)

Renderings of the 65-storey tower previously proposed for 145 Wellington Street West. (Turner Fleischer / SKYGRiD)

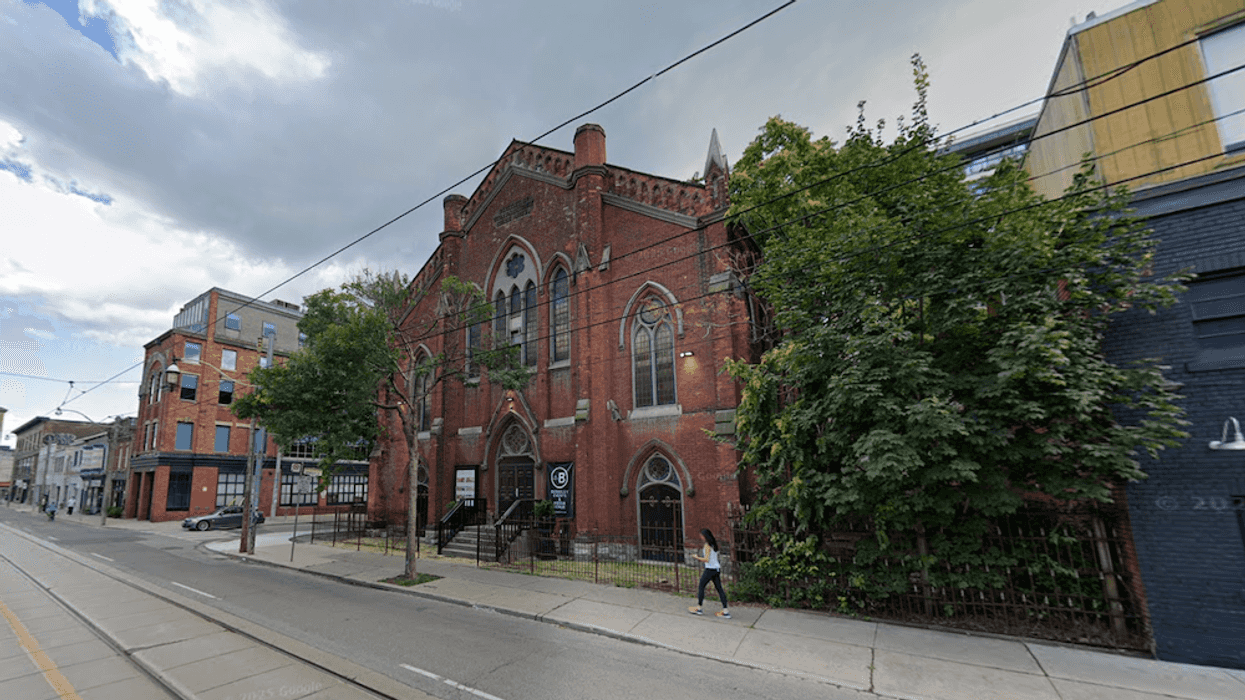

205 Queen Street, Brampton/Hazelview

205 Queen Street, Brampton/Hazelview

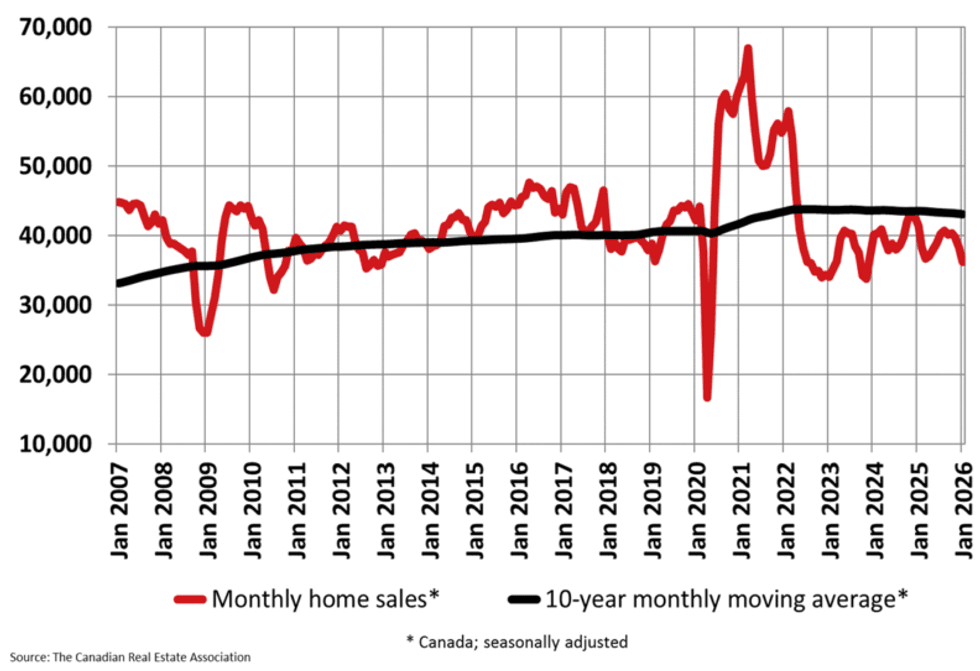

CREA

CREA

Liam Gill is a lawyer and tech entrepreneur who consults with Torontonians looking to convert under-densified properties. (More Neighbours Toronto)

Liam Gill is a lawyer and tech entrepreneur who consults with Torontonians looking to convert under-densified properties. (More Neighbours Toronto)