“Not another condo,” exclaim countless Toronto residents daily, as they throw up their arms and shake their heads in disbelief at news of yet another towering new development.

But they shouldn’t be so surprised.

Density is the name of the game when it comes to the Greater Toronto Area’s (GTA) urban planning agenda – especially in areas surrounding current and upcoming public transit hubs. With new provincially-passed legislation as a driving force behind it, these neighbourhoods are in store for a drastic transformation in the not-too-distant future.

Yet, most Toronto residents are in the dark on the density front, says city councillor Mike Colle (Ward 8: Eglinton-Lawrence), who is deputy mayor for the north part of the city. He says his ward – a midtown area heavily serviced by the TTC – has more development applications than most provinces. Colle points to a stretch of Marlee Avenue, from Lawrence down to Eglinton Avenues, as an area that’s currently overwhelmed with development applications for high-rise residential buildings. Tellingly, this stretch is serviced by three TTC stations; Lawrence West, Eglinton West, and Glencairn.

“This isn’t just density; this is hyper-density,” says Colle. “And it’s happening anywhere there is a subway station.”

Colle says that – thanks to quick (see: hasty) decision and policy-making on the part of the Ontario government – most Toronto residents aren’t aware of the fate of many neighbourhoods, which will see their populations grow exponentially in the coming years. Towering new residential buildings are set to reshape skylines (yes, that’s plural) throughout the GTA, as single-family homes and low-rise buildings along transit lines become realties of the past.

“People are in shock when they see all these developments occur in their neighbourhoods,” says Colle. “They don’t know about the dramatic changes in planning rules that permit hyper-density around transit stations. So, in City planning meetings, they’re shocked to learn about 30- and 40-storey buildings, because they’ve never been informed in a systematic way about the changes to the legislation.”

The GTA’s Density Agenda

For those in need of a refresher, provincially-passed legislation requires minimum density requirements set near major transit stations – neighbourhoods defined as Major Transit Station Areas (MTSA) or Protected Transit Station Areas (PTSA). Both are defined as the 500- to 800-metre radius surrounding a transit station. PMTSAs are eligible for inclusionary zoning (an affordable housing component), while MTSAs are not. Either way, we can expect these areas to undergo a massive transformation in the coming decade, with new condo buildings and purpose-built rental developments quickly redefining the landscape.

Driving this forward is the Ontario government’s controversial More Homes Built Faster Act (Bill 23), which was passed in November 2022. With an aim to rapidly spur development, the bill has contributed to the influx of building permits for these towering developments along transit lines by enticing developers with lower fees and speedy approval times.

Located within a short walk to transit stations, these new residential buildings will share two common characteristics: they’ll be sky-high, and they’ll house a limited number of vehicular parking spots.

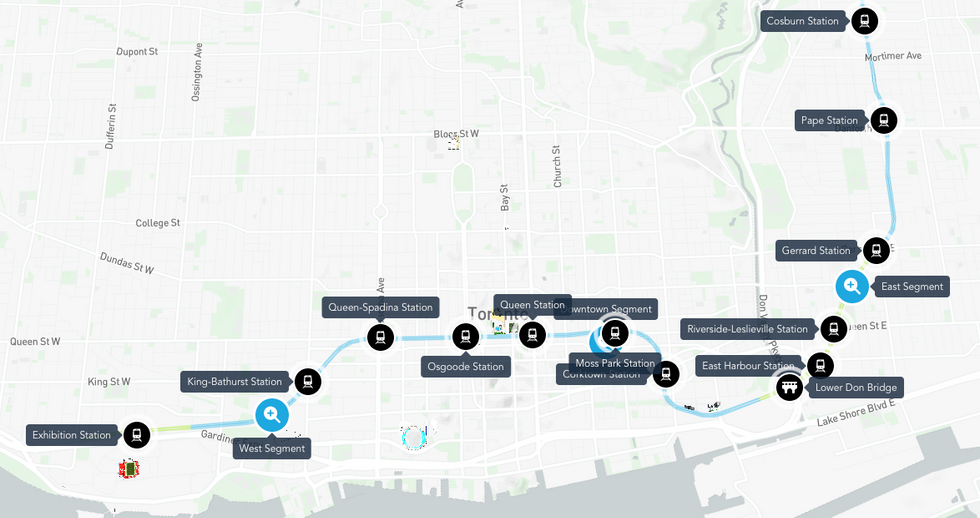

In short, we’re moving fully forward in the direction of Manhattan when it comes to density and our relationship with the car (or, more appropriately, lack thereof). The GTA’s ambitious plans for widespread transit expansion – whether this means the upcoming 15.6-km Ontario Line (which will run from Exhibition Place up to the Ontario Science Centre), the Yonge North subway extension, the Scarborough Subway Extension, or new GO stations – is front and centre to this.

Take the Yonge and Steeles intersection, for example. This is the site of the future Steeles Station, part of the Yonge North Subway Extension, which will extend the TTC’s Line 1 service north from Finch station to Vaughan, Markham, and Richmond Hill. Recently, the area surrounding the intersection has been the subject of many applications for towering residential developments. Earlier this month, Arkfield Developments submitted a development proposal for 7-17 Nipigon Avenue, located east of Yonge Street, south of Steeles Avenue East. Currently, this plot of land houses five single-family detached residential dwellings. If all goes according to plan, these homes will be demolished to make way for the development, which will stand 50 storeys tall, with a five-storey podium, and contain 620 units.

Similarly, a stretch of Sheppard Ave. East in North York – along the historically underused Line 4 Sheppard – has seen an influx of development proposals since the implementation of MTSAs. With it has come the disappearance of single-family homes and businesses in the neighbourhood. Most recently, an application was submitted to the City to rezone a gas station at 461 Sheppard Avenue East – across from Bayview subway station – to make way for a 43-storey mixed-use tower. If the Sheppard subway line is extended, an option that’s currently under consideration, we can only expect this trajectory to continue, like it currently is in the areas surrounding Eglinton Ave. on the (still pending) Eglinton Crosstown LRT line.

The GTA’s transit-centric development is set to bring much-needed housing supply at a time when Canada continues to welcome immigrants at record rates. The Provincial government recently outlined plans for six transit-oriented communities for the Ontario Line and the Scarborough extension that will create approximately 5,900 new homes in a supply-strapped climate.

The (Public) Pushback

With new transit comes housing – that’s long been the case. But new condos (and purpose-built rentals, for that matter) get a bad rap in a city already plagued by perpetual construction and maddening congestion. Not to mention, NIMBYism. Plus, some people simply don’t want to part with their car, thank you very much.

“I don’t understand this mentality that development is a punishment, but that’s the way it’s treated in Toronto,” says urban planner and architect Naama Blonder of Toronto’s Smart Density. “On the contrary, I live on a street that has so much construction, and I really look forward to seeing what type of retail at grade is coming. Development improves neighbourhoods with new retail, restaurants, public spaces, and parks.”

Blonder says that the future of Toronto is indeed one where the car takes a backseat to transit, walking, and cycling; where residential towers punctuate the skyline surrounding transit stops; and where kids will (happily) grow up in condos – whether we’re ready to embrace that reality it or not.

“I have to give credit to the public; I do think many understand the logic and rationale about having new housing – and that we absolutely need more transit,” says Blonder. “But developers, planners, and politicians need to do a better job to educate and explain this concept. Where are people going to live in 10 to 25 years, if not in mid-rise and high-rise buildings? If we think Toronto is unaffordable now, can we imagine what this place is going to be like for the next generation if we’re not making changes on how we design, approve, and build?”

While there’s no denying this reality, it’s a tough pill to swallow for some to see beloved Toronto spots – whether beloved watering holes (RIP Betty’s and the original Banknote Bar) or long-time family-run flower shops – disappear to make way for yet another condo. You can’t put a price tag on a neighbourhood’s character or history and its accompanying nostalgia.

But even putting nostalgia aside, some worry whether or not Toronto’s infrastructure is suitable to meet the needs of rapid densification. Overwhelmed with development applications, Colle says that many neighbourhoods in his ward – including along Marlee – are currently ill equipped on the infrastructure front to serve such a rapidly growing population. “There’s no libraries, community centres, or anything there to support the influx of people,” says Colle. “But in the areas surrounding Lawrence West, Glencairn, and Eglinton West TTC stations, they are free to build developments of unlimited height and density. Everything gets approved these days.”

A report from Toronto Metropolitan University’s urban planning department called “Density Done Right” – which argues the case for distributed urban density – highlights how “building tall” in the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) region has historically led to challenges with overburdened infrastructure systems. The result is “a mismatch between population density and the provision of services, such as transit, schools, health and community services, and parks and recreation,” according to the report.

To illustrate this point, it highlights how residents in Toronto’s downtown core currently share an average of 4.2 square metres of parkland per person, much less than the city-wide average of 28 square metres. Density in the downtown core is expected to nearly double by 2041.

What Density Means for Real Estate

Increasing density impacts everything from the number of people in local green spaces and grocery stores, to construction woes and the disappearance of views from existing units. Toronto-based realtor James Milonas says both politicians and GTA realtors (himself included, he admits) need to be more proactive at educating their clients about the region’s density agendas.

“I think some buyers have a good sense of what’s going on in certain segments when it comes to transit and density, but some don’t,” says Milonas. “The average first-time home buyer, for example, is pretty tapped into what’s going on in current affairs regarding upcoming transit. When a buyer who relies on transit is looking for their new condo, they’re factoring in their potential transit use, so they’ve done their research.”

Milonas says the lack of parking spots in today’s new builds – especially those surrounding transit stations – is typically not an issue for his downtown clients. “If a buyer is from the city, they most likely don’t have a car, so parking generally isn’t an issue,” he says. “The buyers who are relocating from the ‘905’ region are the ones that want parking. In new builds, one-bedrooms don’t come with the ability to purchase parking anymore. It’s seldom that two-bedrooms will also have that option unless they are of a certain price or square footage.”

With hyper-density comes the disappearance of single-family homes in the immediate vicinity of transit hubs – and huge payouts for their owners once developers come knocking at their doors. “If you live in a house close to a transit station, don’t be surprised if a developer wants to tear it down to build a condo or purpose-built rental,” says Colle. “And if you don’t sell your property, you’re going to be living next to a high-rise.”

Even homes near transit stations that developers don’t have their sights set on (i.e. they aren’t suited for redevelopment) could increase in value with new transit lines. “The advice I would give someone in a single-family home surrounding new transit lines is to sit still on their properties and watch their equity grow,” says Milonas. “We saw it in E04 (Scarborough), where homes from Victoria Park to Kennedy, and Eglinton to Lawrence grew in value and demand [with the Scarborough Subway Extension].”

There is, however, a common worry that hyper-density could actually decrease the value of a home. But this hasn’t been the case in Toronto. The single-family homes surrounding Yonge and Eglinton, for instance – a rapidly densifying neighbourhood that’s seen the influx of sleek residential skyscrapers in recent years – have only shot up in value in the past decade.

Then there’s the commercial real estate element. These new builds inevitably bring fresh new retail and restaurant options to the neighbourhood. Existing small businesses, however, are faced with a double-edged sword. On one hand, increasing density with each shiny new condo brings more prospective new customers. On the other hand, the changing neighbourhood brings increased operating costs. Furthermore, let’s not forget about the fact that perpetual construction negatively impacts foot traffic to storefronts – just ask the business owners along the infamously delayed Eglinton Crosstown LRT line.

While he believes that transit-centric development is key to Toronto’s future, Toronto realtor Nathan Dautovich (PropertyGuys.com) acknowledges that it’s not without its costs. “Some people are getting hurt by these initiatives, particularly small businesses in low-rise buildings near transit hubs,” says Dautovich. “Some are seeing their rents increase exponentially based on the ‘highest and best use’ of the land. So, a typical two-storey building with apartments on the upper level and a storefront on the main level is being charged the same taxes as a high-rise condo. While this makes sense in theory, some small businesses have been ruined financially by these policies.”

Building The Way Forward

The bottom line is that, with Canada’s ambitious immigration targets, there will be no shortage of demand for condo new units.

“Growth is inevitable, as StatsCan just released that Q4 had the highest increase in Canada's population since 1957, and we more than doubled the previous record,” says Dautovich. “We don't have enough homes for all of these people to live in, and high-density neighbourhoods near transit are absolutely part of the solution. The more planning and foresight involved in creating these condo buildings and transit networks, the better.”

The good news on Toronto’s urban planning front is that the development and construction of transit and new homes in its vicinity is happening simultaneously – which wasn’t always the case. “It's good to see more long-term planning in having both transit and new development be built at the same time,” says Dautovich. “There are many examples where either the residential side was built too early (East Waterfront), or the transit side was built too early (Sheppard Subway).”

Of course, Toronto’s density agenda isn’t limited to towering high-rises surrounding transit hubs. With a mission to fill in the “missing middle” with gentle density, Toronto City Council also passed regulations earlier this year that allows for the creation of duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes in neighbourhoods traditionally reserved for single-family homes. But that’s a story for another day.

In the meantime, the Province continues to plough ahead with its initiatives to build 1.5 million homes by 2031 – most of which will have to call transit stations neighbourhood staples if they have any chance of meeting their housing goals.