This is how a “city of neighbourhoods” becomes a city of mini-cities.

A strong economy, growth-oriented immigration, new transit, a backlog of housing supply and massive tracts of land up for grabs as factories and industrial uses fade into history – and at the intersection of these, a big opportunity.

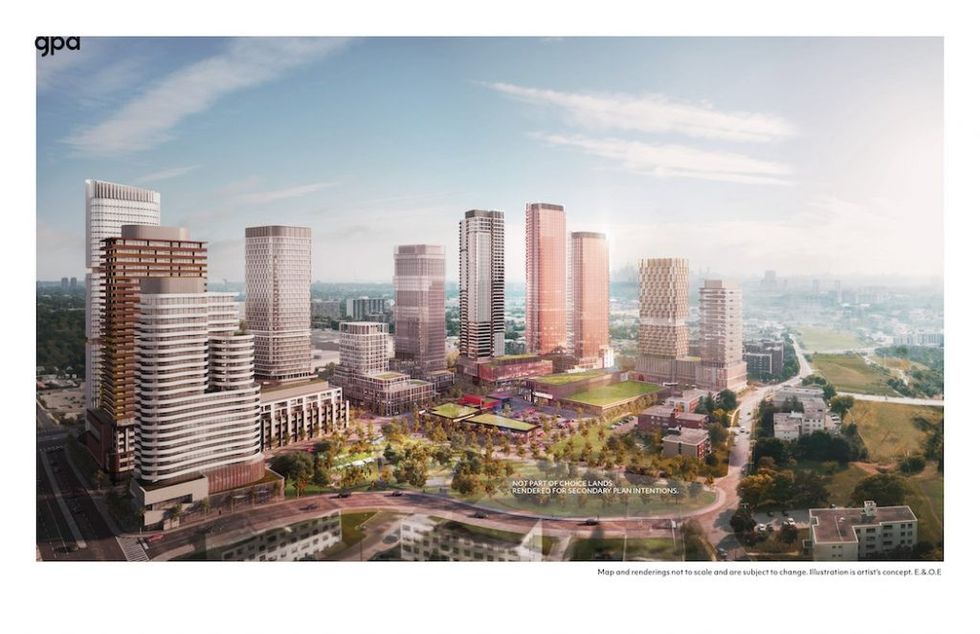

Large-scale mixed-use projects are springing up across the GTA and making enormous contributions to new urban centres in a single footprint. In some cases, they are the centre themselves, aiming to compete with some of Toronto’s oldest neighbourhoods for vibrant communities, cultural draws, and urban lifestyles.

“I think what’s happening is that a whole bunch of big sites are coming onto the table,” says Joe Berridge, city builder, partner at Urban Strategies and author of Perfect City. “It seems to be more of them than I can remember for a while.”

Berridge ticks off a couple of big recent ones: a string of sites in Scarborough’s Golden Mile, the Mr. Christie’s site in Mimico, the “enormous” Downsview. The size of this land allows developers to tap into a variety of revenue streams, from townhomes up to towers, both rental and ownership, as well as retail and office space.

“When you’ve got 100 acres – as opposed to one acre, or even 10 acres – your ability to deploy a much more sophisticated development program is hugely enhanced,” he says. “And you can have a mix of uses, and you want a mix of uses.”

One threat to these complicated and expensive builds is what Berridge calls a “bias to the boring” when it comes to filling retail space. Banks, groceries, Shoppers Drug Marts and chain restaurants are considered the safest retail – convenient but commonplace tenants with good credit ratings.

But residents want exciting experiences, hot new restaurants, mom’n’pop shops, a distinctive sense of community, Berridge says, and a thoughtfully built environment that goes beyond a lineup of towers with basic retail and services at grade.

“They want a sense of place, focal points, they want meeting places,” Berridge says. “They want to go out and sit on the street and have a coffee, meet the neighbours. I think that’s what’s exciting and frankly very pleasant about this whole trend [of large-scale mixed-use]. You’re making much more than just units of housing; you’re actually making a place.”

‘That Sense of Vibrancy’

Placemaking is where Rob Spanier, president of advisory firm Spanier Group, makes his mark.

Born and raised in Montreal, he travelled the globe to work on mixed-use projects and resorts before advising large-scale projects in the GTA. He says it was inevitable that Toronto’s job economy and growth-oriented immigration would create a series of urban centres throughout the region.

“When I got to Toronto, I couldn’t understand how everybody was going to use downtown Toronto from Thornhill, Richmond Hill, Vaughan, Markham, Brampton,” Spanier says. “And about 15 years ago a lightbulb went off in my head saying, ‘Oh, it’s not that everybody’s going to use Toronto – it’s that they’re all going to have their own downtown.’”

Spanier says a true “mixed-use” project requires careful calibration of residential, retail, office, civic, cultural, entertainment and public spaces; he adds that some large projects call themselves mixed-use but don’t quite fulfil the placemaking potential.

“A big part of this thing is that you don’t have to live in the 416, in the central core, to have that amenity and experience,” he says. “You have the sense of community, you have that sense of vibrancy, you have that mix of uses.

“My belief on mixed-use development and true placemaking is that people are going to vote with their feet … And that could be, for some people, third generation children wanting to live next to their parents or grandparents. So, in Vaughan, there’s all this opportunity, the same in Mississauga.”

Urban Life on the Lake

Lakeview Village is poised to redefine what it means to live in southeast Mississauga: 8,000 homes, 1.8 million sq. ft of employment space with up to 9,000 jobs, 200,000 sq. ft of retail, plus waterfront parks, a kilometre-long pier out onto the lake, an innovation district, a cultural hub, and a hotel.

Population: 20,000.

“It’s not every day that you come across 177 acres of blank slate, vacant land on the waterfront in the heart of the GTA,” says Brian Sutherland, Vice President of Development for Argo Development Corp., the lead developer for Lakeview Village. “It just doesn’t really exist. So, you know, we really look at this as an opportunity – working with all of our various partners, the city and other stakeholders – in transforming the waterfront in southeast Mississauga.”

If you put 20,000 people in single-family homes on spacious plots, you’ve made a sprawling suburb. But if you densify the housing, cluster people closer together, and use the remaining space for gatherings and events and destinations that draw visitors from surrounding regions – you’ve created urban life, a mini-city. From scratch.

Sutherland says the measure of Lakeview Village’s success will be lively streets filled with locals and visitors, employees and tourists, students and artists – a community fully self-sufficient and yet welcoming to guests day and night.

“When we look back on this 20 years from now, [we hope] there’s vibrancy, a very urban component,” he says. “Everything we’re doing is trying to not create a sleepy suburban kind of place. Here it’s intended to be active, vibrant, a place that people want to come – not only just to live, but to come visit from across the GTA as a destination spot. To come and walk out almost a kilometre into Lake Ontario on this fully publicly accessible pier. A place where people are going to want to work and live.”

‘A Whole New City Centre, Frankly’

Menkes Developments has been building large-scale mixed-use since the 1990s, says Jared Menkes, executive vice president of high rise residential.

“We rebuilt Empress Walk in North York, which was really the true predecessor to all these ‘live work play’ developments that we’re seeing happening over the last 10 to 15 years,” he says. “The conveniences and the community that’s created [by large-scale mixed-use projects are] really paramount to what people are looking for. It’s really building this mini-city.”

Most recently, Sugar Wharf brings an all-new 11-acre community to Toronto’s waterfront; just ahead, Mobilio and Festival projects contribute to a 75-acre master-planned project at the Vaughan Metropolitan Centre (VMC).

“The subway was recently delivered in the last few years, so that’s really kicked off this new development that you’re seeing, especially at the VMC,” Menkes says. “It’s a whole new city centre, frankly, and it’s going to be home to thousands of people – jobs, shopping and living.”

Menkes predicts a strong future for large-scale mixed-use: larger and more elaborate projects to respond to a new generation of buyers, streaming out further and further into the GTA – especially the 905 – and linked by transit.

The pandemic put city life on pause, but it will come roaring back, he says: “Cities are going to thrive again.”

‘Human Shelving’

Spanier, who advised on the Lakeview Village project, believes the GTA has the potential to be a global leader in large-scale mixed-use in the coming decades. Another prediction: “Downsview is arguably one of the greatest opportunities that the GTA has for large-scale mixed-use.”

It’s the future, not a trend. Even though buyers are paying for the square footage in the sky, Spanier says their concept of “lifestyle” is cultivated on the ground.

A close friend, a successful real estate agent in Florida, told Spanier something interesting five years ago as they stood on a balcony overlooking Sunny Isles Beach, outside Miami.

“He goes, ‘Look at this. See all that? That’s human shelving.’ If you think about that statement of the human shelf – where do people live?” Spanier says.

“They live on the ground floor, but 50 feet up. That is the experience. And I think that projects – and developers and cities – need to put so much more focus on that ground floor, 50 feet up, because that is truly where people are going to live and love the places they choose to be.”

The future of GTA living, you might say, will be an elevated experience.