Edmonton's housing crisis is not as well-publicized as those in Vancouver and Toronto, but it exists nonetheless.

Shortly after Prime Minster Justin Trudeau reshuffled his cabinet in late July and named Sean Fraser as the new Minister of Housing, Edmonton Mayor Amarjeet Sohi — along with Calgary Mayor Jyoti Gondek and Alberta Minister of Seniors, Community, and Social Services Jason Nixon — wrote an open letter to Fraser highlighting the housing crisis in Alberta and making their case for more federal funding.

"We were deeply disappointed to learn that CMHC only selected six applications out of 39 from Alberta [for the Phase Three Rapid Housing Initiative funding announced in July]," the trio wrote. "The funding to these Alberta projects for $38.3M is only 2.5% of the $1.5B RHI fund allocated in Phase Three, and the 200 units funded for Alberta represents only 3.8% of 5,200 units funded through this initiative. Given that Alberta is Canada's fourth-largest province representing approximately 12% of Canada's total population, we find these disproportionate results very troubling."

The trio also said that they are concerned that the federal government does not fully comprehend the challenges Alberta and its large municipalities are facing, including "unprecedented in-migration, which often includes newcomers who are escaping violence in home nations and require access to affordable family units," such as those fleeing from Ukraine.

Meanwhile, according to commercial real estate brokerage Avison Young, the average office vacancy rate in downtown Edmonton was at 17.1% in Q2 2022, and has steadily increased since then to 18.2% in Q3 2022, then 18.3%, then 19.2%, and — most recently — 20.5% in Q2 2023.

In terms of the amount of physical space, downtown Edmonton carries a total office inventory of 18,116,089 sq. ft across 131 buildings, according to Avison Young. About 3.7 million sq. ft of that is now vacant, which is more than the total office inventory in Surrey (3,166,534 sq. ft), the second-largest municipality in British Columbia.

Downtown Edmonton now has too many office buildings that can't compete in the market anymore, says Cory Wosnack, the Managing Director of Avison Young's Edmonton team.

"They're becoming functionally obsolete," Wosnack says. "A number of these buildings have a large amount of vacancy, in non-vibrant locations, and are often older office product, which just doesn't lend itself to compete well for today's office occupier."

He adds that whereas other Canadian office markets have seen a so-called "flight to quality" — tenants moving towards the high-end properties — Edmonton has seen a flight to vibrancy, where an average quality office building in a vibrant location can beat out a higher quality building in a less vibrant location. Nonetheless, Edmonton's office vacancy is too high, and there are no strong indicators that it's about to get better.

As has been the case in many major metropolitan cities across North America, when office vacancies start becoming a problem in a place where there is a clear need for housing, the local government and real estate industry start taking a look at converting that office space for residential uses — often also referred to as "adaptive reuse."

The Conversion Conversation

At the tail end of a Council meeting on March 14, Edmonton City Councillor Andrew Knack notified Council that he would be moving a motion requesting that the City work with industry stakeholders and the provincial government to find a way towards "increasing the number of new residential and office conversions to residential in Edmonton's downtown."

He then did so at the next regular Council meeting, held on April 4, and the motion was seconded by Councillor Anne Stevenson, officially launching the City's efforts towards developing an incentive program to facilitate office conversions.

The City is currently working with industry groups — such as the local chapters of the Urban Development Institute (UDI), Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA), National Association for Industrial and Office Parks (NAIOP), Canadian Home Builder's Association (CHBA), and the Edmonton Downtown Recovery Coalition — to develop the incentive program, with a general structure expected to be presented to the Executive Committee on October 13.

And anticipation is building in the local real estate industry.

"The conversation now, from the developer and investor side, is becoming much more frequent, because they see Edmonton as being very opportune to look at a conversion strategy that introduces a different kind of residential product," says Wosnack. "We have a number of successful new developments that are offering new residential, but there's actually a gap where the residential market can actually capitalize really well on conversion of office buildings that address a mid-market calibre of residential product."

According to the provincial government, Alberta has seen about 40,000 to 60,000 new immigrants every quarter in the last year, which is second only to Ontario. As Alberta's capital city, it's safe to say that a significant portion of those new immigrants will be settling down in Edmonton, which means the need for housing will continue to increase.

"That's where the conversion strategy really presents itself in an interesting way, because the product that you usually get from a conversion of an office building is typically the mid-market quality and pricing that aligns well with what the new Albertans and the young adults seek," says Wosnack.

Aside from providing housing, another aspect of the conversation is as it relates to property taxes.

The land size of Downtown Edmonton makes up only about 1% of the entire city, Wosnack points out, but it provides about 10% of all its tax revenue. Over the past few years, as the value of the office buildings in Downtown Edmonton has declined, the revenue the City can collect has also declined, creating a shortfall that the City will have to make up for somewhere — and that somewhere could very likely be residential property owners, if no action is taken. Converting those declining office buildings into residential uses would restore their values and address the tax revenue shortfall.

Asked what he saw that inspired him to introduce his motion, Councillor Knack points to what happened in Calgary.

"Calgary had a bigger issue with vacancies starting even before the pandemic, and what I was watching is the loss of valuation from those properties in their core ended up having a massive impact on small businesses outside of the core," Knack told STOREYS. "There were businesses that were seeing — over the course of just a couple of years — 50% to 70% property tax increases."

Knack says he was worried that what occurred in Calgary could also happen in Edmonton and that he wanted the City to be proactive rather than reactive, and to have something in place before it becomes a bigger problem.

"There's also a livability and safety component," says Knack. "Unlike a lot of other major North American and Canadian cities, our population living in the downtown core is much smaller than most major cities, and this will help with that. We're dealing with, like many major cities, challenges around homelessness and safety and security, and one of the best ways to help with that is to help more people living in the core. The more people that are on the street walking to restaurants, walking to recreational opportunities, and being out there, the more eyes on the street, the greater the perception of safety and the greater the actual safety."

Second Time Is The Charm?

Although the City of Edmonton is looking to establish a new incentive program, it's not exactly a new endeavour altogether.

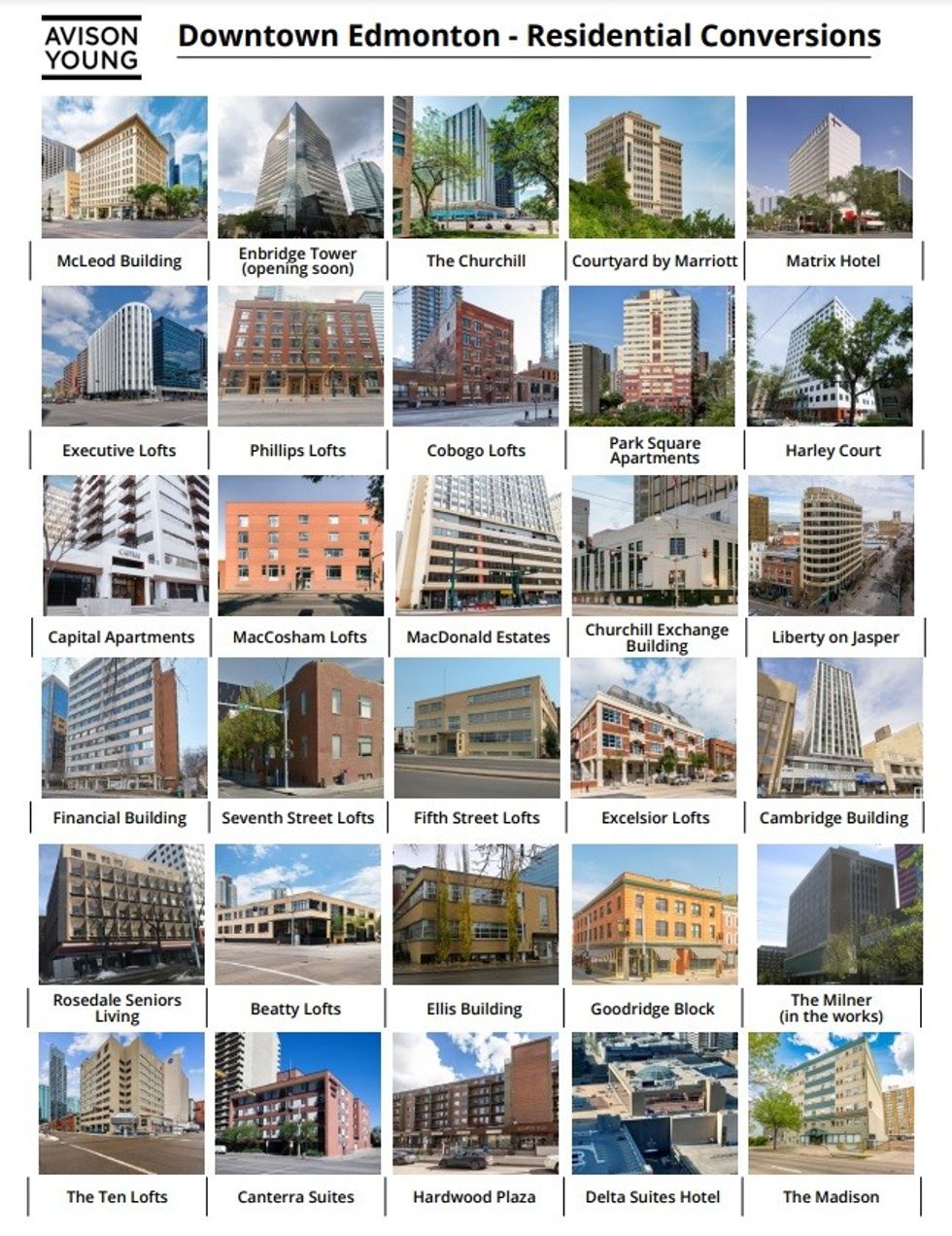

In 1997, the City created the Capital City Downtown Plan, which provided financial incentives of $4,500 per unit created via conversion, which ultimately led to the successful conversion of about 16 office buildings in the early 2000s.

Wosnack — who has been at Avison Young since 1995 — recalls the circumstances then, and they aren't much different from what is happening today. Office vacancy rates were over 15%, many of the vacant spaces were aging and could no longer compete in the market, and the City was concerned about the resulting lack of vibrancy.

The program was very successful and the population of downtown residents grew by about 10,000 between 2000 and 2007, which brought more street-level retail, cafes, grocery stores, and other amenities that make an area vibrant. Simultaneously, the office market also improved. The office vacancy rate fell from about 19% to 6%, rental rates doubled because there was no longer an oversupply, and the value of the office assets also improved significantly.

"We actually were able to help serve two markets," says Wosnack.

This time around, it's easy to look to Calgary and its successful office conversion program, which has garnered attention from across North America as proof of concept that office conversions can be done en masse and not just as one-offs.

"When I started at BOMA three years ago," says BOMA Edmonton President and CEO Lisa Baroldi, "I raised the topic and it was a lukewarm response. Some people said 'The numbers don't work, so why do we even talk about it?' Then I sat at a panel over a year ago with Rob Blackwell [COO of Aspen Properties] around the inception stage of Calgary's program, and he pulled me aside and said 'I know people say the numbers don't work, but they could, and they have in the past, if the City and the Province and others get involved and provide some incentives.'"

Baroldi says that Blackwell told her about the program Calgary was working on, and that hearing somebody from the industry say that office conversions could be done en masse was something that really opened up the discussion.

Calgary's incentive program, officially called the Downtown Calgary Development Incentive Program, ultimately ended up providing $75 per sq. ft of existing office space converted, up to a maximum of $15M per property. Five projects were granted funding in years past, with five more announced earlier this year. The City has also expanded the program to provide $50 per sq. ft of existing office space that's converted into a post-secondary institution, as well as 50% of the total costs towards demolition of an office building.

Since Councillor Knack introduced his motion and work on developing the program began, Baroldi says that she believes there is room for improvement in terms of collaboration, particularly in contrast to Calgary.

"Calgary's program came together because they have a real estate advisory committee, a group of people who meet regularly with the City on various topics, and they actually co-created the program," says Baroldi. "And I don't feel like that's happening in the same way here in Edmonton, because our real estate advisory council was disbanded. One of the things I'd like to see happen is that council reinstated, so when there are topics like this, there's a group like this that's co-creating and sharing information, a team effort, as opposed to a 'we'll pick up the phone and we'll talk to you a few times and we'll create a report.'"

Baroldi says that, as of early August, there isn't a working group or task force doing the heavy lifting that she is aware of, and that she believes that strong collaboration between the City of Calgary and the industry is a big reason why Calgary's program was successful and not just a program that exists but nobody subscribes to.

"At this stage, at least, it's more of an exploration by the City of what some of the options are. Now, sometimes in the past, we've been burned in that, in their mind, that's a deep consultation or even co-creation, and we're thinking 'thanks for the half-hour conversation, but when we mean co-creation, we mean the weekly calls and the working group with the City, industry, and community working to understand the ins and outs.'"

The Magic Number(s)

In terms of what those options may be, all parties interviewed for this article agreed that there are multiple potential incentives that would make a difference, whether it be dollars per sq. ft or door, permitting prioritization, or property tax assistance.

Adopting Calgary's $75 per sq. ft of office space converted would be somewhat disappointing, some said, as Calgary's number was set years ago and market factors have changed since then — and not for the better. In a statement to STOREYS, Executive Director of UDI Edmonton Metro Kalen Anderson said her group believes the incentive should be closer to $100 per sq. ft with a total pool of $100M to support the conversion of 1 million sq. ft, and that any property tax exemption would have to last around 10 to 15 years to be meaningful.

"While a laudable goal, office-to-residential conversions present many challenges and will not be a silver bullet on its own," Anderson added. "For example, whereas purpose-built rental may have 90-93% efficiency, an office building may have 75%. For 100,000 sq. ft of space, that means a developer can only use 75,000 sq. ft of space to use and build revenue from. Coupled with increasing costs, office-to-residential conversions present more risk for the developer. They require more capital, more debt costs, and more construction costs."

Even before getting to those stages, it can be costly just to assess whether a building is suitable for conversion. Oftentimes this involves extensive physical inspections of the buildings that can take weeks or months, with no guarantee that the findings will make the option to convert a no-brainer. Some have turned to artificial intelligence to assess their buildings. Others, such as the City of Calgary when it was developing its incentive program, turned to an algorithm created by Gensler's Steven Paynter.

Earlier this year, Avison Young published a report concluding that approximately 34% of office buildings in 14 major markets in North America fit the base criteria for conversion: having been constructed before 1990 and with a floorplate below 15,000 sq. ft. Edmonton was not included in that estimate, but Sheila Botting, Avison Young's President of Professional Services, Americas, says that broad-stroke estimate generally holds true for Edmonton as well.

However, zooming in and narrowing that criteria, Wosnack estimates that there are about 10 office buildings in Downtown Edmonton that he believes are excellent conversion candidates, which are primarily smaller Class B or C office buildings located closer to or within the Government District around the Alberta Legislature Building. That area is also currently home to two office-to-residential conversions that are already underway: The Milner by Westcorp and the conversion of the Enbridge Office Tower into The Peak.

Anand Pye, Executive Director of NAIOP Edmonton, estimates that there may be even as few as six or seven. He also says the NAIOP would be happy to see an incentive program centered on creating new residential rather than specifically converting office buildings, because he believes Downtown Edmonton has too much parking and that removing some would also be a positive.

A group of about 50 people, consisting of various stakeholders and members of Council, took part in a walking tour of Downtown Edmonton in mid-August to get a deeper understanding of the office buildings that could be converted and what they could look like, says Councillor Knack, who also estimates the number of potential buildings to be at least seven.

The product of Knack's motion will be presented to the Executive Committee on October 13 and is expected to include the recommended incentive program, which Council will likely consider for approval later in the month.

Knack says the program will likely be about $100 per sq. ft and $100M in total to be dispersed. He adds that much of the funding will be provided closer to project completion, which will give the City a year or two to figure out where the funding will come from.

"Even on the eve of an incentive program being announced, just the very possibility of it has brought interest into the city," says Wosnack. "It has the potential of bringing new capital into Edmonton, it's addressing an opportunity to bring more residential, and an opportunity to course-correct the office market. Even without the results of the discussion with the industry stakeholders and without knowing the details of what this incentive program will look like, there is a lot of excitement."

- How Peoplefirst Developments Decided to Convert Calgary's Petro Fina Building ›

- Adapt or Die: Why Converting Offices Into Homes Hasn't Taken Off in Canada ›

- Edmonton Ends Exclusionary Zoning With Bylaw Overhaul ›

- Calgary And Edmonton Office Markets Both See Strong Q3's ›

- How Peoplefirst Developments Converted The Cornerstone ›

- Edmonton Approves Sale Of First Parcels Of 200-Acre Exhibition Lands ›

- Edmonton Mill Woods Town Centre's First Phase Plans Revealed ›

- Edmonton UDI And CHBA Merge To Form BILD Edmonton Metro ›

- A Changing Of The Guard Has Occurred In Edmonton's Office Market ›

- Guardian Office Building In Edmonton Under Receivership Listed For Sale ›

- Edmonton Proposing $553M Action Plan To Revitalize Downtown Core ›