“The local residents have given it a nickname -- The Wafer -- because it’s so narrow, tall, and thin,” says Toronto City Councillor Mike Colle of what he calls a “precedent-setting” building application.

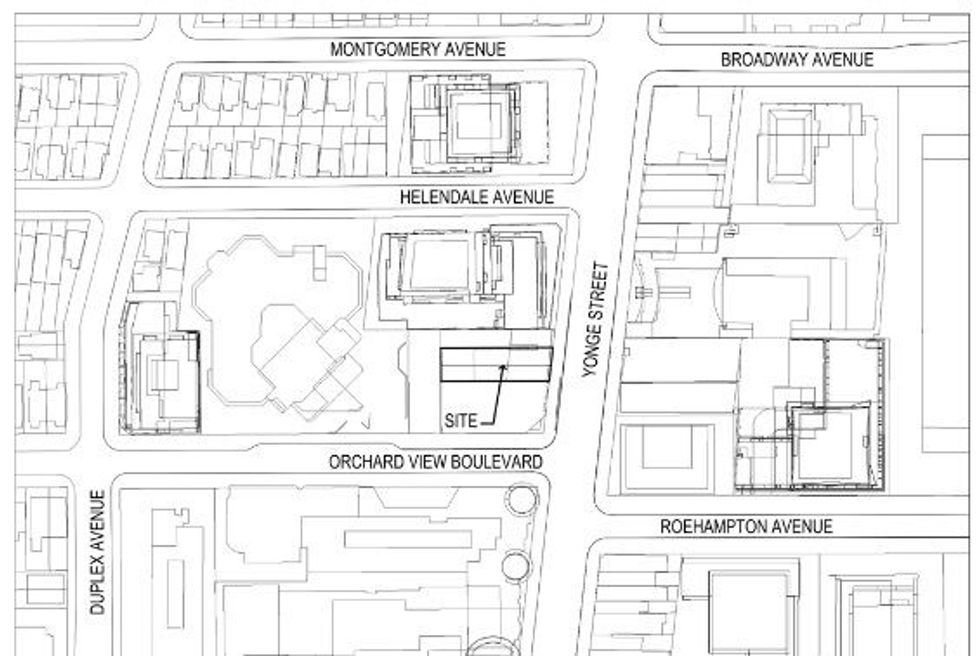

In short, he isn’t a fan of the proposed 50-storey condo development at 2350 and 2352 Yonge Street in his midtown ward. “It’s such a narrow lot; it’s only two retail storefronts and comes to 40 feet of frontage,” says Colle. “You’re trying to build 323 units for people to live in on an extremely narrow space in a vertically-focused building. This isn’t the right space to build so many units because it’s such a small lot.”

The extremely narrow bit of real estate is sandwiched between two smaller buildings, highlights Colle. “To the south, there’s an RBC bank, and to the north, there’s another retail outlet,” he says. “They’re in a really tight spot. It’s also the first application I’ve had where the applicant has said that they’re planning zero on-site parking, which is precedent-setting.”

Colle acknowledges both a decreasing reliance of Toronto residents on the car and the December 2021 move by the City of Toronto that removed its parking minimums for new residences. In fact, the zoning bylaw amendments remove most requirements for new developments to provide a minimum number of parking spaces and adds limits to the number of spaces that will be built. In theory, this permits developers to build spaces based on market demand.

Inevitably, Toronto is moving into an era where the car is taking a back seat to other modes of transportation, like cycling or, most notably, public transit. But Colle thinks that zero parking spots and zero vehicular access to the building -- as is seen in the proposed Yonge Street development -- could pose problems in our Amazon and Uber-saturated culture, and he questions how the design will be mechanically practical.

“You can’t even enter the building by car at all; there’s no drop-off area because it’s Yonge Street, so you have to walk right into your building from Yonge,” says Colle. “Most buildings have some sort of entrance around the back, but this has one in the back through an easement, but their property isn’t connected to the easement. So, there’s no clear pathway to the back for things like garbage trucks, maintenance vehicles, Wheel-Trans drop-offs, and deliveries.”

The proposed tower's developer, Bazis Inc., did not respond to multiple requests for comment by the time of publication.

With a lack of underground parking, Colle questions what happened to usual parking requirements to accommodate people with disabilities and visitors. His greatest concern comes down to basic accessibility.

“In these buildings, there are always service and maintenance staff coming in to service the building, fix elevators, or fix plumbing,” says Colle. “These service people need access to these places. Not to mention garbage pickup. It won’t be easy to get a truck in and out of there.”

The parking situation is a different issue. “Residents aren’t as dependent on the car as they were in the past,” says Colle. “The reality is that people can’t afford to pay $100K for a parking space underground. People realize that living at Yonge and Eglinton and parking and driving your car isn’t an easy thing to do. So, more and more people are using transit and Uber. So, there is less need for parking than there used to be.”

But “less need” doesn’t mean zero need, says Colle.

With that said, Toronto urban planner Naama Blonder says that those who are dependent on their cars simply won’t live in the building, calling it a lifestyle choice. “I don’t think it’s extreme,” says Blonder of the zero allocated parking spaces. “The entire question comes down to the distance from the proposed development with zero parking to public transit. When we invest more in more public transit, the way we use cars is going to change in the coming years.” The proposed Yonge Street development is just a few blocks from the Eglinton TTC station and within walking distance of countless shops, restaurants, and services.

Blonder also highlights the cost factors associated with underground parking. “Underground parking is not only less sustainable, but there’s the affordability factor,” she says. “It costs so much to excavate and is expensive to build. The numbers could be 16% to one-third of the overall cost, depending on the height of the building. It’s also less affordable for residents to have parking as part of the equation. Looking into the future, twenty years from now, what are we going to do with underground parking levels? We can’t convert them to anything; they’re going to be unusable.”

Then, there’s the density issue that’s ruffling Colle’s feathers. In addition to a move away from the car, another impossible-to-ignore Toronto trend is an agenda to increase density, one shiny new condo at a time. But is jamming a 50-storey building with 324 units into a 40-foot lot between two buildings a stretch? He thinks so.

“They’re really challenging the rules on this one,” says Colle. “The basic norms are challenged. It’s also kind of extreme to go 50 storeys. Maybe 30 or 40 -- but not 50." But he’ll have to work with it.

“It’s too bad that this isn’t a project that takes the full corner into account,” says Colle. “A year and a half ago, there was a group who was discussing that whole block with City planning staff -- from the RBC building, those two storefronts and the third one. They had asked our planning staff for a proposal; all of a sudden, they come back and they only have the two storefronts -- not the bank on the corner or the storefront at the end.”

This, of course, changes everything.

“It seems unfortunate that that would have been a reasonable project with the whole block, but this middle business is a missed opportunity to plan the corner properly so that you can get in and out of the building,” continues Colle. “You’d have width and access from Orchardview and from Helendale. Then, it would have been a workable building. Now, the fact that the RBC on the corner isn’t part of it really makes it an awkward application. But, we’re going to keep working on it. Maybe they can convince the bank and the other store to join in the application, but right now it’s a tight fit. We’ll see what they have to say, but hopefully they can strike a deal with their neighbours.”

At the end of the day, the reality remains that Toronto is characterized by a relentless lack of housing supply. Some may argue that the only way to grow is up -- even if it’s tall, skinny, and car-free.