It will soon be pricier than ever to create new housing in the City of Toronto, thanks to a proposal to hike development charges that has builders up in arms.

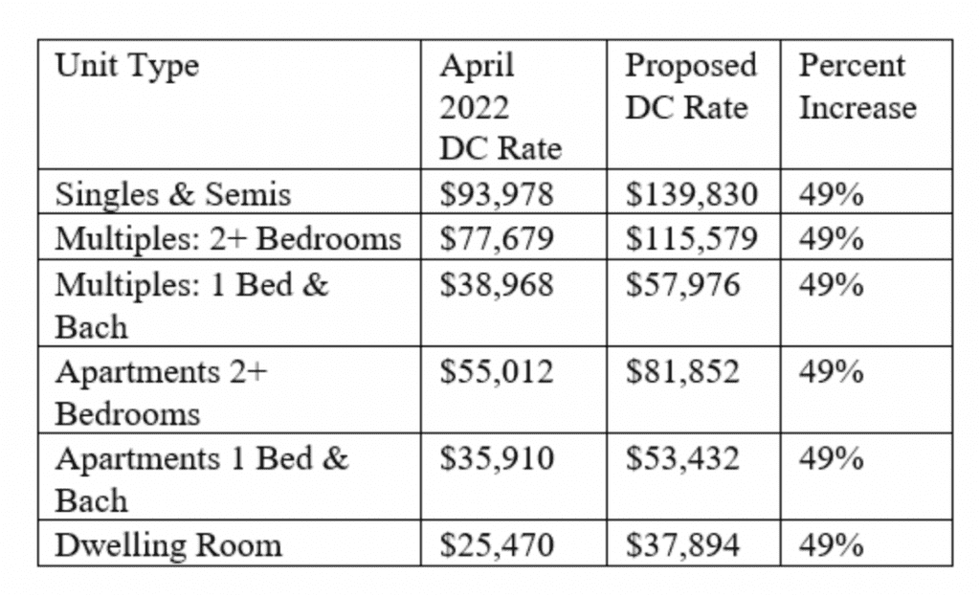

As part of a need to update its key growth funding tools and reassess associated bylaws, the City has unveiled a new scheme for a 49% increase for development charge rates, applicable to every residential housing type. The hike would take effect when the existing development charge bylaw expires next April, though it remains to be seen at this time if the charges will be a one-time implementation, or phased in over a number of years.

Development charges are a cost-recovery mechanism for the city, based on the premise that “growth pays for growth”; they’re a one-time fee collected when building permits are issued, and help pay for the associated capital investments required to support new development such as roads, transit services, and sewer infrastructure, just to name a few. It’s important to note they can only be used for these growth-related capital costs, and cannot be siphoned off for operating costs or other city expenditures.

Under legislation, these charges must be assessed every five years by a third-party consultancy that looks at required capital projects over a 10 to 20-year horizon and divides their associated growth costs by the number of planned units to determine the rate. The last development charge increase, which was a similar size, was introduced in May 2018.

Anyone constructing a new building, making an alteration or addition to an existing building that increases its number of residential units, or changing the purpose of a building, are generally subject to these charges.

Smaller Projects ‘To Go Cold”

While higher development charges will make it more costly for developers of all sizes to build, the ones to be hardest hit are smaller builders looking to create gentle-density mid-rise or infield housing, says Greg Gilbert, Director of Planning and Design at Trolleybus Development.

“Adding these fees on -- sure, downtown condos in Yorkville can stomach these, and still meet their profit margins, but these additional $30,000-per-bedroom rates that the City is proposing are going to hurt projects on Kingston Road in Scarborough, in Etobicoke and downtown, that don’t have the same upside on pricing,” he tells STOREYS. “They’re just developers that maybe aren’t the Menkes and the Tridels of the world, and they probably already have difficulty getting financing, and with high interest rates, these additional fees are just going to make these projects not profitable. And lenders aren’t going to lend on them.”

READ: "Solid Case" For for Bank of Canada to Make 1% Rate Hike as Inflation Soars

“These are fees that are going to make these projects on the peripheries that are finally viable, non viable again. I think you’re going to see a tougher time in making projects in these kind of gentrifying or forgotten areas; you’re finally seeing development there, which is great, but you’ll see that go cold because of this.”

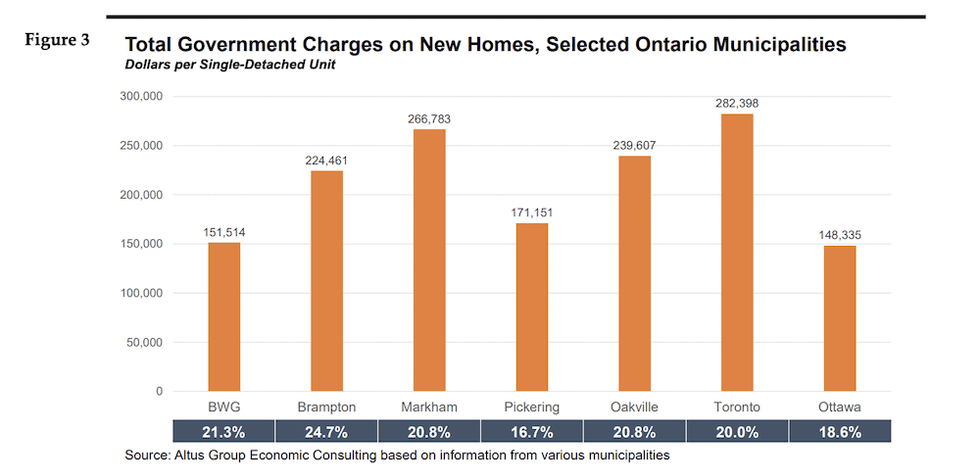

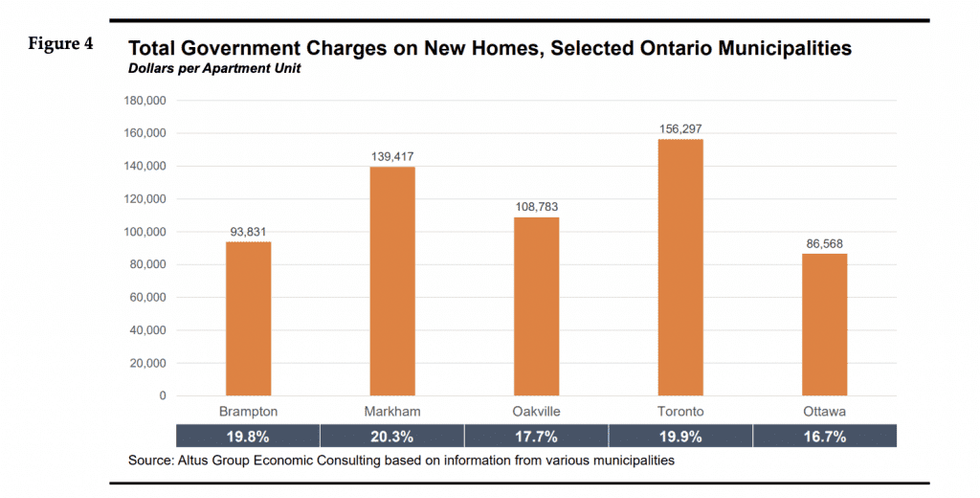

In addition to pricier outlays for builders, development charges are passed down to homebuyers. A previous study conducted by the Building Industry and Land Development Association (BILD) found that in the Greater Toronto Area -- which has some of the largest developer-incurred government charges in North America -- they contribute to a 27% markup on the average new home cost. The study also found the average government-imposed charges on a new home in the GTA was $222,652 for low-rise residential, and $124,582 for high-rise.

“It reverberates across the industry for all new developments, and it’s going to create upward pressure on prices,” says Brandon Donnelly, Managing Director, Development, Slate Asset Management LP. “That is, the first thing that developers will do in response to this is look to increase prices in order to absorb these additional costs. The costs have to go somewhere and I think there’s often discussion or at least the city will look at this and say land prices will come down when there’s a new increase in charges or a new policy like inclusionary zoning.”

Donnelly adds that there’s a held belief that when new policies are put forth, land prices will come down to help partially offset their impact -- but as anyone who’s witnessed the steep appreciation of Toronto land prices over the last decade can attest, that’s hardly been the case. According to the the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board, the average price of a resale home in the city was $1,299,894 in February, while the average newly-built home benchmark price clocked in at $1.86M.

Rising Cost Fears Exaggerated Says City Controller

Andrew Flynn, Controller at the City of Toronto, says builders’ fears of skyrocketing costs are being taken to the extreme, and that the resulting increase is smaller than perceived.

“If we’re just talking about development charges, the point I would make about affordability is 49% sounds like a big number, but the average change for apartment units is $22,000,” he told STOREYS. “I compare that to the average price of condos just in 2021, they went up by 20% to $800,000. Folks are saying, ‘Forty-nine percent, oh my god, they’re making things unaffordable,’ and I’m going, ‘It’s $22,000 per unit.’

“It’s just another input, like the cost of drywall, the cost of windows that the development community has to consider as part of their pro formas. But the revenue they’re generating is not a one-to-one relationship. A 20% increase on $800,000 is a much bigger dollar number than $22,000 in DC charges.”

The City has indicated that in addition to the five-year requirement to reassess development charges, it must also do so due to “some of the provincial legislative changes that take effect on September 2022” -- referring to the province of Ontario’s More Homes More Choice Act – as well as Bill 197, the Covid-19 Economic Recovery Act 2020.

It points out that as due to Bill 197, development charge rates for new applications were frozen, and instead calculated based on the date of certain planning applications, leading to delayed funding over last two years.

“DC payments for non-profit housing, rental housing, and institutional developments are now collected in installments beginning at occupancy over five and 20 years, with interest. Installment payments and deferrals have resulted in $100M of delayed funding since 2020 which will need to be covered through interim financing,” the City states.

According to the latest development charges study conducted by consulting firm Hemson, the City must prepare for an increase of 430,000 people and 185,000 employees in Toronto by 2041. The proposed capital program is “rooted in an estimated $22.5B growth related capital forecast over 10 and 20-year planning periods”, leading to “fully calculated rates in the DC study amount to a rate increase up to 49% for residential development and 40% for non-residential development.”

“I think the point that needs to be raised here is that growth is supposed to be paying for growth, so the increase in infrastructure is a direct requirement or cause of the rate change,” says Flynn. “But if you actually look at how the city is able to recover, it is a significantly lower percentage than is required. So if you look at the property tax base, if you think of the other main revenue tool that the city has from a point of view of infrastructure, that the property tax base is, in fact, subsidizing growth. So I appreciate and understand that any good businessman doesn’t want to see his or her costs go up but in the broader context, somebody has to pay for the infrastructure, and if it’s not the growth, then it’s the existing.”

That a hefty development charge increase is prompted by the fact that the City has kept its residential property taxes at artificial lows over the last number of years is rubbing the building industry the wrong way; the city has the lowest tax rate in Ontario, at 0.611013. That’s led to a capital projects backlog that requires catching up in today’s inflationary environment, says Gilbert, who points out that the City already has considerable development charge funds in its coffers.

“I think a lot of it is we didn’t upgrade things when we had the chance. There’s a lot of money -- $5B I think -- sitting in the City’s bank account from already-collected development charges. That money should have been put out years ago to build new sewers, to rebuild roads, to build transit, and now, the cost to build those things has probably doubled, just like everything else in our lives, in the past 10 years. So there’s just a backlog of capital works projects that are in this DC study that developers are paying for, which would have been half the price to build if we did it 10 years ago,” he says.

An "Exercise in Cognitive Dissonance" on Housing Supply

The building industry points out that, given all the current narrative surrounding Canada’s housing supply crisis, implementing more overhead costs will only make the issue more acute. According to the Canadian Real Estate Association, national inventory currently sits at 1.8 months, the second-lowest level in history, and well below the 5.5 months that is typical. The federal government has also pledged in the most recent budget to spend $10B on new housing supply creation.

“One of the things we’re imminently aware of is, the people that suffer the most as a result of this are the ones who can least afford it, and there’s just no way around a lack of supply,” says Richard Lyall, President of Residential Construction Council of Ontario (RESCON). “You can have all kinds of demand-side measures, enabling people to be able to save more, with the federal government’s recent budget proposals -- and that’s all good.

“The industry produces all housing; doesn’t matter if it’s social housing or whatever it is, it’s the private market that actually builds the stuff -- and [the private market is] the last part to really engage in this is at the municipal level. And then this thing pops up, and it’s like an exercise in cognitive dissonance. You’ve got this crisis, and these various challenges and problems, and out they pop with [this]."

Adds Donnelly, “This is why the industry is reacting in the way that it is, because this runs counter to our efforts to increase housing supply and efforts to increase affordability. It’s frustrating, I think, for the industry because it’s really speaking out of both sides of one’s mouth, right? What do you want? What is it? Is it more housing and more affordable housing, or is it to increase prices?”