When most people watch the Tokyo Olympics, they are filled with a sense of awe and inspiration as athletes from around the world push their bodies and minds to do incredible things. But when I watch the Olympics, my mind goes to Tokyo’s urban planning policy and what it has to offer Toronto.

Back in 2012, I travelled to Tokyo right after graduating from architecture school. I was a new architect and excited to explore a new place, new styles of architecture, and new urban design strategies. While I was there, I learned about Tokyo’s urban planning policies, which are quite different from the norms here in North America.

After living in Toronto for 8 years now, I’ve had a chance to reflect on how parts of Tokyo’s urban planning policy could be used to improve urban planning in Toronto. With the whole world now looking at Tokyo as it hosts the Olympics, it felt like the right time to share the top three things I wish Toronto would adopt from Tokyo’s urban planning policy.

Flexible Zoning

Tokyo-Yokohama is the largest urban area in the world with a population of over 38 million and a density of approximately 2,642 people per square kilometre. To get a sense of that level of density, you can compare that to the Greater Toronto Area that has a population of 6.5 million and a density of 849 people per square kilometre. There are many reasons why Tokyo is denser than Toronto, but perhaps one of the contributing factors is Tokyo’s much more flexible zoning that allows for density to take place without as much bureaucracy and as many approvals as are needed in Toronto.

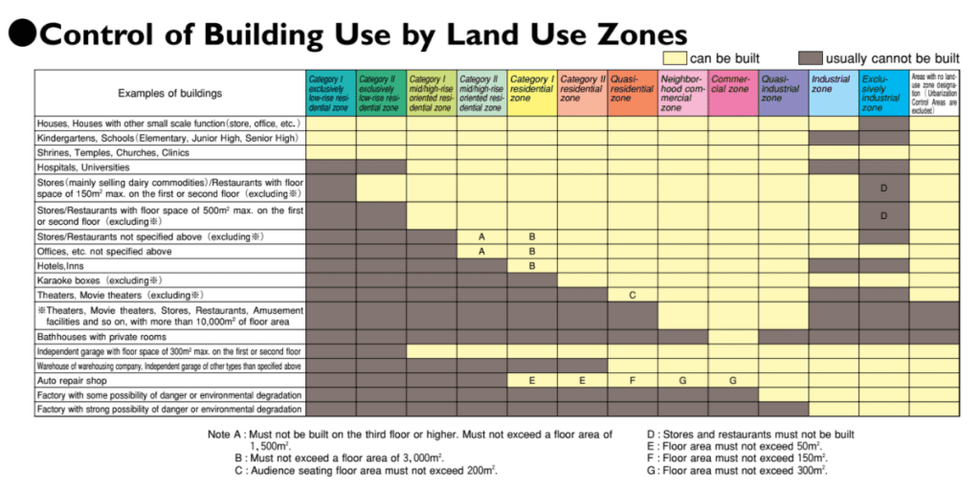

One of the most unique things about Tokyo’s zoning compared to Toronto (and most of North America) is that basic zoning guidelines are set by the national government and then implemented by cities. The national government outlines 12 zones, ranging from low-rise residential to industrial. These zones are transparent and flexible with even the strictest low-rise residential zones allowing home-based businesses and small local retailers. Floor Area Ratios (FAR) -- the maximum ratio of building area to lot size -- are still used to control for building size, but no restrictions are made on the type of built form allowed. Even in low-rise residential areas, anything from duplexes to triplexes to apartments and beyond are allowed, as long as they conform to the FAR parameters.

The other interesting aspect to this zoning is that the less sensitive a zone is, the wider range of uses it allows. For instance, the most restrictive residential zone only allows houses, schools, shrines, and houses with small functions (i.e. offices, stores). The next less restrictive zone allows for all of those plus small stores and restaurants. The next less restrictive zone allows for all of those plus hospitals, universities, and larger stores and restaurants. There are some exceptions for heavy industrial areas, but for the most part this pattern continues so that less sensitive zones allow nearly any kind of use.

Toronto’s zoning policy could not be more different. Toronto has more than 25 core zone types, with many exceptions and site-specific provisions within those 25 types. The number of rules and fine-tuned details make it hard to innovate and respond rapidly to changing community needs. More flexibility could be a step towards more (affordable) housing and more complete communities.

Utilization of Small Space

Tokyo’s zoning is a big lesson for Toronto, but we should also take note of Tokyo’s creative approach for utilizing small parcels of land and building tall. Too often in Toronto, small and awkward plots of land are left empty because conventional designs don’t fit the small space. Height restrictions in many North American cities also make it impossible to build tall on some sites. In Tokyo, however, innovative design has led to a number of thin, yet tall buildings in many areas. These designs are also made possible by the fact that Tokyo has exemptions that allow for more height the further back a building is from the street.

Tokyo’s utilization of small spaces was part of the inspiration behind a recent design we at Smart Density did called the “mini-mid-rise.” The mini-mid-rise is a slim building designed for small lots that conforms to Toronto’s zoning policies and urban design guidelines. It may seem a little unusual for Toronto’s streets today, but the concept has been incredibly successful in places like Tokyo.

Transit Stations and Mixed-Use Hubs

Japanese cities like Tokyo do a great job of incorporating mixed-use facilities into their rail hub operations. Known as Rail Integrated Communities (RIC), this type of development has become one of the major forms of urban regeneration in major Japanese cities. RIC is similar to the North American concept of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) but is exclusive to rail-based networks and tends to exist on a grander scale.

RIC helps ensure long-term financial resilience for Japanese railways, which are privately owned and don’t receive much financial assistance from the government. The lack of government funding combined with the high costs of rail network construction necessitates this type of mixed-use development. The integration of office, shopping, dining, entertainment venues, and community leisure spaces in the railway hubs helps the railway companies achieve a higher level of profitability.

READ: Ontario Proposes Building ‘Vibrant’ Transit-Oriented Communities Along Ontario Line

Luckily, Toronto is already starting to implement some of these concepts through a push for more transit-oriented development. Examples include plans for East Harbour and throughout places in the GTA like Cooksville, Newmarket, and Oakville. The visions for these transit-oriented communities are still being developed and have yet to be fully executed, but it is a hopeful sign that Toronto may be on the right track in following Tokyo’s lead in this area.

With that said, it’s important to remember that part of Tokyo’s success with RIC is that less than 30% of the city’s population commute by automobile. Compare this to the 70% of Torontonians that commute by car and it’s clear that we still have some work to do if we want to get the most out of true transit-oriented communities like what has been done in Tokyo.

Tokyo has a lot of urban planning lessons to offer Toronto, as do many cities around the world, and the Olympics are a good reminder of this. The Olympics are an international coming together and celebration of people, ideas, and culture. So, over the next couple of weeks, let’s enjoy the thrill of the 100-metre dash and the suspense of gymnasts flying through the air... but let’s also consider what we can learn from other cities around the world so we can make our own the best it can be.