The country needs major reforms to address what has become an epic affordability crisis.

The news that the housing market is undergoing a major slowdown, and is even seeing falling prices in many places, is music to the ears of Canada’s stressed-out, priced-out younger generation.

In comments on social media, would-be homebuyers are rooting for a house price crash, in the hopes that it will finally mean a return to affordable housing.

But the cost of housing in Canada has ballooned to the point where even a major correction in prices wouldn’t return the market to its historic affordability norms -- at least not at today’s interest rates.

READ: Make Less Than $225K? You Can't Afford to Buy a Home in Toronto

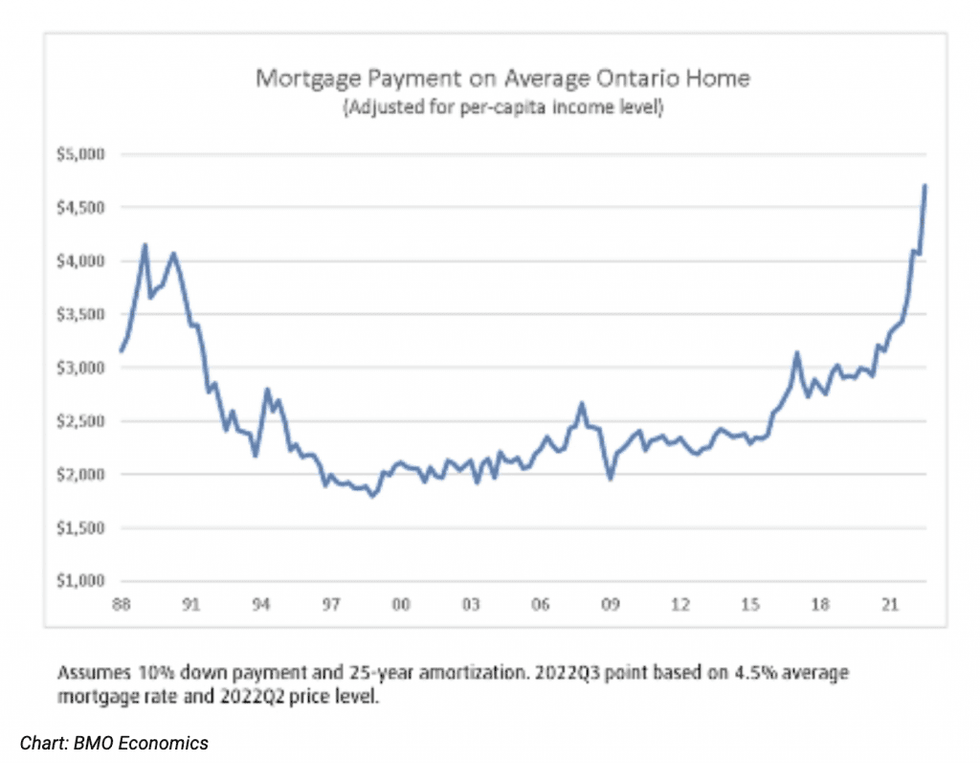

Recent reports from Royal Bank of Canada and National Bank of Canada show housing is the least affordable it has been in 30 years, since the peak of the 1980s/1990s housing bubble.

The average selling price of a house in Canada jumped some 40% in the two years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and now “the Bank of Canada’s ‘forceful’ interest rate hiking campaign will further inflate ownership costs in the near term,” RBC economists wrote in June.

“Higher rates will affect virtually every buyer across the country,” but the priciest markets will be hit hardest, they said, concluding that RBC’s measure of housing affordability is “on a path to worst-ever levels.”

With would-be buyers seeing their purchasing power shrinking, many are staying put in rental housing, and that’s putting upward pressure on rents.

Advertised rents jumped between 18 and 26% in Toronto and Vancouver over the past year, depending on the apartment type, Rentals.ca reports.

At first blush, the house price decline looks like good news for buyers (and bad news for owners). The average selling price of a house in Canada has fallen nearly 20% since its peak in February, to around $665,000 in June. That’s 1.8% lower than a year earlier.

But from the point of view of affordability, rising mortgage rates mean things are considerably worse than a year ago.

In a recent client note, Bank of Montreal economist Robert Kavcic estimated that, with the Bank of Canada’s July rate hike, the mortgage payment on an average-priced home in Ontario will have ballooned by more than 50% since early 2021, from around $3,000 to $4,700.

Nationwide, the jump in mortgage costs is nearly as bad.

Over the past year, as discount rates for five-year fixed-rate mortgages jumped from around 1.7% to 4.3%, the monthly payment on an average-priced house jumped from around $2,200 to $2,900, a 32% increase. That’s even with the slight drop in the average house price over that time.

At these rates, to get back to last year’s $2,200 monthly payment, the average selling price would have to fall all the way to $510,000, a drop of another 23%.

And that doesn’t get us to affordable homes -- only to last year’s already high housing costs.

Sorry, homebuyers. A house price crash won’t help much, because what falling home prices giveth, rising mortgage rates taketh away.

Canada Needs More Housing

It’s becoming increasingly apparent -- to renters, homebuyers, real estate insiders and policymakers alike -- that the country needs more housing.

According to a 2021 report from Scotiabank, Canada has the lowest number of housing units per capita of any G7 country.

A report earlier this year from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. found the country needs to build 3.5M more homes than planned by 2030 to get back to the affordability levels of 2003 and 2004 -- the last time CMHC says housing was affordable.

Of those new homes, 1.85M additional units need to be built in Ontario alone, the report said.

Most agree that there are no quick solutions to the problem, and building more housing faster will require political action.

“Step one has to be ending exclusionary zoning,” says Jacob Dawang, an advocate with More Neighbours Toronto (MNTO).

The group is among a growing number of “YIMBY” (“yes in my back yard”) organizations that are taking on “NIMBY” (“not in my back yard”) activists who oppose new development in existing neighbourhoods.

The situation for renters in Toronto has turned dire, Dawang says. Tenants have no leverage in today’s market.

“If you don’t take the price your landlord gives you, there are 10 people behind you willing to pay that price,” he says.

The space to build new housing is there, groups like MNTO argue, if only cities changed their approach to development and allowed more densification of low-rise areas.

Dawang notes that on two-thirds of land in the City of Toronto, it’s illegal to build anything other than single-family homes.

He notes that Ontario’s housing affordability task force suggested in a report this spring that owners be allowed to build up to four residential units, and up to four storeys, on any plot of residential land.

The idea, which is currently being studied by Toronto, was inspired by a law passed last year in California, which is also dealing with high house prices and a shortage of affordable housing.

The law passed despite opposition from hundreds of California municipalities that argued it would undermine local control of development. It’s now the subject of a court challenge by four California cities. But even so, its passage was a turning point in the fight between NIMBY and YIMBY, a sign that, as housing costs continue to rise, politicians are coming under greater pressure to do something about affordability.

More Land, Please

Frank Clayton, Senior Research Fellow at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development, has his doubts about the potential to densify Toronto’s detached-home neighbourhoods.

“It’s just not going to happen,” he says.

In his view, it’s a virtual political impossibility to get municipal leaders and single-family home owners to agree to serious densification.

While Clayton doesn’t oppose it, he is among many experts who say densification alone won’t address Canada’s housing needs as the population grows.

“We’ve got to open up a lot more land, both in developed areas and in undeveloped areas,” he says.

And “it can’t just be 60- or 80-storey apartment buildings, a lot of people don’t want that.”

Home buyers still want detached homes, surveys show; about half of new buyers want a single-family home, while only about a quarter of new housing in Greater Toronto is detached houses, Clayton says.

He argues for a balanced approach that densifies neighbourhoods but also allows for the development of low-density housing on the fringes of urban areas.

If that doesn’t happen, people will simply move further away from the city to find the housing they want, Clayton argues, which increases commuting, and “you defeat your purpose of reducing greenhouse gasses.”

He notes that people have been leaving the Greater Toronto Area for cities outside of its sprawl-limiting Green Belt.

“There is a dispersion of the population taking place,” especially since the pandemic, and people are now able to live further away from places of work than before, Clayton says. To keep the trend from intensifying, you have to provide more affordable housing in cities.

“You have to flood the market with supply to get prices coming down, that’s the only way.”

Self-Financing Public Housing?

Some experts have been arguing that governments should get back into the business of building public housing – something that was common in North American cities during the 20th century, when urban housing was much more affordable despite rapid population growth.

“Massively expanding public investment in non-market housing” would be “transformative” for cities, says Alex Hemingway, a senior economist and public finance policy analyst at the B.C. office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

By “non-market housing,” he means government-built, or at least government-subsidized apartments. Hemingway has been advocating for governments to start building what he calls “self-financing housing.”

Cities or provinces would borrow to buy land and build apartments on it just like any developer, but they wouldn’t add to the public debt – they would pay off the cost from the revenue generated by renting out the housing units.

By not adding a profit margin on top, Hemingway estimates these units would rent out for 15 to 20% below what private developers could rent them for. And on top of that, an ambitious government could subsidize the rent for low-income families as well, Hemingway says.

A Political Problem

But Hemingway recognizes a major problem: Canada’s real estate industry is very consciously benefitting from the housing shortage. In a recent Twitter thread, he illustrated how many developers and real estate income trusts (REITs) are counting on the housing shortage to drive up their profit margins.

Any attempt to get cities and provinces back into the business of building affordable homes would be resisted by businesses and industry groups with deep pockets. And such a plan could also meet with resistance from homeowners who worry public housing could reduce their value of their own homes.

All the same, Hemingway points to cities around the world as proof that things can be done differently. One example is Tokyo, which has very flexible zoning rules and no such thing as areas just for detached homes.

Another is Vienna, where the city directly owns a quarter of the housing stock, helping to make it one of the more affordable European capitals.

Dawang argues public pressure from those who can’t afford housing can make a difference, and in Ontario the “YIMBY” push for densification has already had an effect.

In the most recent provincial election cycle, “every major political party had supply (of housing) as part of their platform,” Dawang noted. “We need to see more of that.”

For him, it’s a question of whether or not he will be able to live the life he wants in the city of his choosing.

“If I ever want to have a family here (Toronto)... it’s just not possible now. There are no attainable options.”