We are living in an era when historic wrongs are being righted – and in the minds of many who are involved in Vancouver’s real estate sector, a major wrong was the way the City of Vancouver treated Millennium Development.

Until Millennium built the Athlete’s Village for the city’s 2010 Winter Olympic Games, they were riding high on several successful developments and a solid Lower Mainland track record that went back to the early '80s. Originally from Iran, and educated in the UK, Peter and Shahram Malek had been embraced by the City of Vancouver for the delivery of city infrastructure projects that they delivered on time and on budget, even writing them letters of reference. City staff had encouraged them to bid on the Olympic Village, along with four other established developers – and having missed out on opportunities like the Woodward’s Building, they embraced the idea.

In the end, the Malek brothers built an entirely new community comprised of eight city blocks, nine acres of park, 21 multi-storey buildings, and 70,000 square feet of retail – all within the ridiculous time frame of just 30 months. But before it was even complete, the project had been tarnished by city hall’s relentlessly negative and often incorrect messaging that the developers were in over their heads and had blown the budget by coming in at $1 billion instead of the forecasted $750 million, according to a new book about the Malek family and the project.

The media played its part as well, portraying the project as a problem that Mayor Gregor Robertson and the Vision council had inherited, and the Village as a “ghost town.”

In fact, says journalist Richard Littlemore, the project came in at $630 million and the City recovered the debt as well as an additional $70 million, while the Malek brothers endured huge financial losses and suffered a reputational hit. Far from a ghost town, Olympic Village is today one of the city’s most vibrant and popular neighbourhoods.

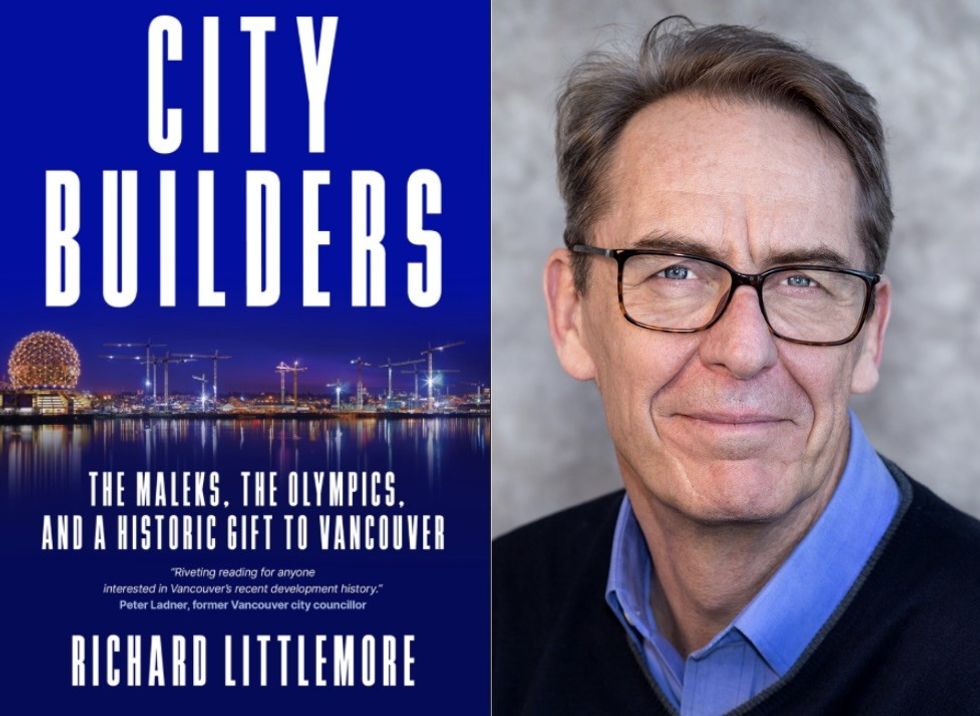

Instead of celebrating the Maleks for achieving the impossible — building an entire community in two and a half years, and amid the global economic downturn of 2008 and 2009 — the City pushed them into receivership and eventually seized most of their assets, even attempting to take their homes, according to Littlemore’s book, City Builders: The Maleks, The Olympics, And a Historic Gift to Vancouver.

When the City ultimately boasted of paying down the Olympic Village debt they’d assumed, they left out some important details, Littlemore says. The City had sold off market rental and commercial space, but they had also charged Millennium a super high interest rate for the loan (while paying a much lower rate to their new lender); they seized and liquidated the Maleks’ assets that took decades to amass, and which had been given as security; and they bulk-sold the last 67 units to the Vancouver based Aquilini Group for $91 million. That option to sell in bulk, writes Littlemore, was denied to Millennium.

Like all developers, the brothers had created a shell company, called SEFC, to oversee the project, which is the company that was pushed into bankruptcy.

The Maleks always intended to push through with the project, with an eye to recovering costs once it had been completed. But instead of allowing the Maleks the opportunity to recover from the economic crisis, argues Littlemore, in 2010 the City pushed their SEFC company into receivership and handed it over to accounting firm Ernst and Young, who then pushed SEFC into bankruptcy.

“The Maleks, despite having been assailed from every direction and having lost almost all of their equity, were still formally and legally in the black in all of their dealings. They were never in receivership personally or in bankruptcy in any way,” says Littlemore.

But when they came up $8 million short on their first high-interest rate loan repayment of $200 million, the City took over whatever Millennium owned of the project, as well as all assets they had put up as security.

“A big bank or lender would never have called a loan when the project was already complete,” Peter Malek says in the book. “On the contrary, a bank would have been happy to extend more time on an investment that was clearly secure in the long term, and at a rate well above market.”

He adds: “They were just totally and utterly ruthless.”

Littlemore said his book came about because of former co-director of planning Larry Beasley, who encouraged the Maleks to give their long-overdue version of events. The Maleks were initially reluctant, but fortunately for Littlemore, they had maintained thorough records from that time. And they allowed him to take a journalistic approach. To protect himself, Littlemore fact checked the Maleks’ version and had the book lawyered.

The big question is why it took a decade to defend themselves.

“This is a big part of the reason why this story didn’t get told accurately at the time,” Littlemore says in an interview. “First of all, they are really private guys, not stand up and shriek-into-the-wind [types]. Super private. And they were humiliated, incredibly embarrassed, because the narrative prevailing at the time was kind of somewhere between nasty and paternalistic, ‘oh these immigrant pikers who got in over their head.’

“If Larry Beasley hadn’t talked them into doing this book, they still wouldn’t be talking.”

Littlemore points out that a lot of the debt incurred was when the Maleks lost control of the project. For four years it was under the control of the City and receivers Ernst and Young.

“The only way you could imagine a loss of $300 million is if you were believing [mayor] Gregor [Robertson] and [councillor] Geoff Meggs when they were saying the City was on the hook for $1 billion. The City was not on the hook for $1 billion. They billed them [$630 million] and according to their own their calculations in 2014, they recovered all of that, entirely.”

Littlemore also points out that other developers would have walked away from their initial deposit and protected the assets they had put up as security. The city’s then-director of real estate services Michael Flanigan, who later went on to work for BC Housing, is quoted in Littlemore’s book: “This had to be the most ambitious project in North America at the time. No one else in the sector could have built that many units at once; and any other developer would have walked.”

If they had walked, it would have been a potential disaster for the city and for the Olympics. But they stayed the course, believing that once complete, the citizens and politicians would appreciate the quality and design of the Olympic Village, said Littlemore. And senior city staff were encouraging them with words of support, so they felt that confident it would work out.

What they hadn’t expected was the changing political climate when the Vision party entered the scene. Vision mayoral candidate Gregor Robertson was behind in the polls and NPA party Peter Ladner was expected to win the 2008 election. The Vision party, writes Littlemore, used the financial struggles surrounding the project to their advantage, making the incumbent NPA party look as if it had bungled the job and cost taxpayers. As a result, Robertson and Vision enjoyed a sweeping win and continued to use the Olympic Village criticisms as political leverage in two more elections.

“I honestly believe they won three elections in a row very much with the help of this issue, because they were getting killed in that first election,” said Littlemore, adding that he is also friends with Ladner.

The political agenda premise would help explain why the City held a bizarre press conference to complain about deficiencies and show a leak from a toilet in one of the suites, when their chief aim should have been to get the project complete.

In the book, Shahram describes the experience as “very painful,” a financial and reputational hit. They were also deeply hurt by the media’s inaccurate portrayal of them being bankrupt. Although they suffered a major setback, they continue to build throughout the Lower Mainland.

Up until they submitted their bid, the Maleks had second thoughts about the deal, which had its problems from the start. Instead of getting title to the Village land, the City would retain ownership until after the Olympics. Anyone who’s borrowed money knows how hard it would be to get a $750 million loan on a leased property. But the City refused to renegotiate, wanting to retain control of such an important piece of the Olympics. Then-Mayor Sam Sullivan told Littlemore he has since regretted the short-term leasing requirement.

Millennium could only find a New York hedge fund called Fortress willing to provide financing, at a variable interest rate that averaged 10.5%. The City also agreed to co-sign for $193 million, to make up for the fact that the land couldn’t be used as security.

According to the City, they provided the $193 million guarantee, as well as a completion guarantee as part of the agreement with Fortress, exposing the city to “the entire financial risk of the project.”

A surprising detail that Littlemore brings to light is that when the City took over the Maleks’ loan from Fortress, they found lenders willing to refinance at much lower rate of around 2.25%. But the City continued to charge the Maleks at around 10.5%. The marked-up loan, he says, cost the Maleks around $110 million. They had other unexpected costs too, related to the security of an athlete’s village, the delivery of 370 below-market units, and ultra-ambitious environmental building standards.

Millennium had borrowed $320 million from the American hedge fund, according to the book. When the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis happened and Fortress cut them off, the Maleks went to the city and asked for $100 million in bridge financing to keep construction going.

In an in-camera meeting, the finance committee, made up of NPA and Vision members, unanimously approved the financing. But someone leaked the arrangement, which sparked the media-driven scandal. And that was when the narrative changed against the brothers, and it seemed like a campaign was building against them.

“Vision Vancouver’s accusations of secrecy and financial incompetence worked like a charm,” writes Littlemore.

For his part, Geoff Meggs, a Vision Vancouver councillor at the time, said he has not read the book and doesn’t plan to “revisit all those details” regarding the numbers. But he believed the city’s exposure was “to the tune of $1 billion,” and he criticizes the previous council for choosing “the best price” as opposed to “the best project.”

“They [the Maleks] were counting on — and many people did in those days, that the market would never go down. Everything would keep marching forward. And they made a very big bid. And the Sam Sullivan council was happy to take it.”

As for the city, he says, “It had an obligation to the International Olympic Committee to have the village ready in time for the games in 2010. There was no option to stop. Secondly, the Maliks had gone out and borrowed from a hedge fund at a very high rate of interest to finance the project. And the backstop was the City of Vancouver. So, they can quarrel about the debt. The fact is that the City of Vancouver was on the hook to fund Millennium to complete the project, and it was unable to do so on its own. It was passing that debt through and that became an issue in the 2008 election, and because of that concern during the election, Vision Vancouver, Gregor Robertson, promised to have a complete review of the books and an audit and release the results, which we did.

“By taking that debt over and getting the hedge fund out of the way and bringing in cheaper financing that was available to the city, we saved $90 million in one day. So it doesn't sit well with me to have the Maliks come back after this period of time and say they were badly treated. The city was left facing a deadline, which it was obligated to complete. The entire prestige of the province with regard to the Olympics was at stake. And by hard work and tremendous effort, we were able to actually recover the debt and complete the project on time. So, it's literally an attempt to rewrite history, which people are entitled to do. But I think the facts are very obvious.”

The Maleks, meanwhile, have argued otherwise, and have — finally — submitted for public debate their own much-needed version of events.