Laneway homes have become a solution to relentless housing supply issues in pricey cities like Vancouver and -- more recently -- Toronto.

The City of Vancouver is celebrated as a leader in Canada’s laneway home movement; back in 2009, it rezoned 95% of single-family areas to permit laneway homes behind primary residential structures. The initiative was designed to increase rental housing supply with minimal disruption to existing neighbourhoods. Over 3000 laneway homes have since been built in Vancouver.

After passionate voices called for its adoption for years, Toronto finally followed suit and passed a bylaw permitting the construction of laneway housing in 2018. According to the City of Toronto, as of May 2021, over 200 building permit applications for new laneway homes have been submitted to the city.

Allowing more than one standalone property on a plot of land that was formerly reserved for a single-family home adds houses to the market in cities characterized by stubbornly low supply. It also opens up access to neighbourhoods for new residents, adding to its character in the process.

But not everyone will be thrilled to live near a laneway house -- at least, not in parts of Vancouver -- according to one recent study from UBC to be published in the Journal of Urban Economics. The study crunched numbers from real estate sales across Vancouver from 2009 to 2017, focusing on the price of homes that had neighbours with laneway houses.

Researchers found the presence of a laneway house within 100 metres of a property on the pricey West Side of the city was associated with a 2.8% lower sale price on neighbouring properties. Neighbours immediately beside a new home with a laneway house experienced an even larger dip, selling for 3.8% less, on average, than those beside new houses with a garage but no laneway home.

The highest priced properties saw the highest drop in value if they had a laneway house next door, at a significant 4.7%, according to the study.

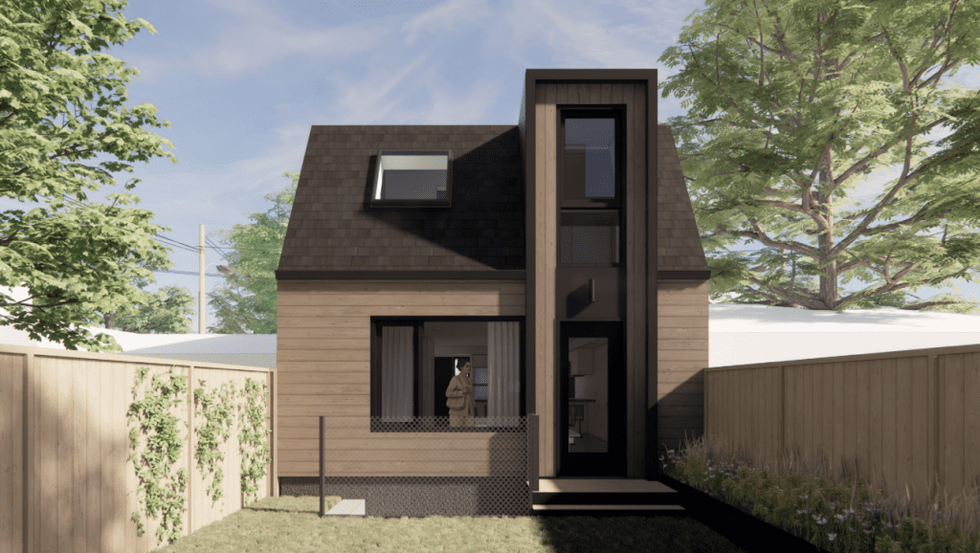

READ: Another Stylish and Spacious Laneway House Hits the Toronto Market

Tellingly, the research found that the correlation between a neighbouring laneway home and a property price decline was practically non-existent for median and lower-valued homes. In the more affordable East Vancouver, the impact was almost zero.

“The overall effect is around 2.8 per cent, but that’s because the effect is so much larger at the high end. In many areas the effect was much smaller,” says UBC Sauder associate professor and study co-author Dr. Tsur Somerville in a press release. “I found that really striking.”

The researchers determined that laneway homes decreased neighbouring property values in more affluent areas because people may be concerned the additional density will put more pressure on amenities like parking and schools, or -- frankly -- they may have a distaste for renters. But mostly, according to researchers, neighbours simply don’t like the fact that laneway homes tend to look into their backyards, which limits the enjoyment of their outdoor spaces.

“The pattern in the externality, near zero for lower-priced properties and large and significant for higher-priced properties suggests a much higher willingness to pay for privacy, absence of neighbourhood congestion, or the absence of residents of a different socio-economic class (renters) among wealthier households,” reads the report. “The policy implications of our results depend on welfare weighting by income and tenure, though with equal weighting they are negative.”

The main takeaway, say the authors, is that the costs and benefits of added density really depend on neighbourhood type.

But do wealthy Torontonians share the same sentiment? The reality is, we’re unlikely to see a spike in laneway homes in Toronto’s most affluent areas in the first place.

“When you think about the fabric of Toronto, the most affluent neighbourhoods aren’t structurally equipped to accommodate new housing under the laneway guidelines,” says Paul Johnston, a Toronto-based realtor who specializes in unique urban homes. “’Laneways of Rosedale and Forest Hill’ is a pretty short book, as these neighbourhoods were the earliest of suburbs, where the servicing that laneways provided weren’t much required.”

READ: One-of-a-Kind Toronto Laneway House + Studio Sells for Record Amount

So, then, the presence of laneway homes in certain areas is more a structural consideration, says Johnston.

“Nobody on the Bridle Path is clamouring for laneway housing, but nobody in the Bridle Path has a laneway anyway,” says Johnston. “But when you look at the bookends of downtown – say from High Park to the Beach – what you see is a large web of streets with adequate laneway service that I feel are embracing laneway housing.”

In Toronto, Johnston says that laneway homes can actually add to property values.

“There are lots in great laneway neighbourhoods like Trinity Bellwoods, the Annex, Leslieville, and Roncesvalles, where laneway suites are a possibility are worth more today than before the laneway guidelines,” says Johnston. “The land is worth more because the opportunity to enhance and expand usage has grown -- either by building a laneway home for income or for additional family space.”

While not everyone may want them in their backyard -- or in their neighbour’s backyard -- the reality is that laneway homes can offer forward-thinking solutions to supply issues and enrich the fabric of city neighbourhoods in the process.

READ: Vancouver Mayor Reintroduces Plan to Allow Six Homes on Single Lots

“I think one of the resounding successes of vibrant Toronto neighbourhoods is their diversity -- a diversity of incomes, life stages, affluence, backgrounds… and so, to that end, laneway housing presents a new opportunity to further widen that perspective,” adds Johnston. “I think a lot of people hoped that laneway housing would replace basement apartments, which often lack for light, proper ventilation, and decent living space. But with only 200 or so permits having been issued in the city so far for laneway properties, this clearly isn’t the case.”

While the idea behind laneway homes is to theoretically increase rental supply, in Toronto, laneway homes are hitting MLS like never before to entice homebuyers, seemingly not renters -- some with price tags of north of $3M (yes, you read that correctly).

Some of the city’s shiny new laneway homes are only attainable to wealthier buyers. Part of the issue comes down to supply; although they’re increasing in prominence, Toronto laneway homes are still few and far between (literally).

“Of course true freehold laneway opportunities are immensely rare; the guidelines only imagine them as ancillary residences, but the demand is in lockstep with the ongoing desire to foster more diverse, inclusive, and exciting neighbourhoods,” says Johnston. “It’s gentle density, that won’t change the fabric of the city, but will enhance housing opportunities. And that, I dare say, I precisely what we should be striving for.”