Provinces across Canada may have a hard time meeting their affordable housing goals, says the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), but it's not due to slow government action: labour shortages are to blame.

"We will not be able to build our way out of the housing supply problem as significant labour capacity constraints exist across most large provinces in Canada," the CMHC stated in a new report published Thursday.

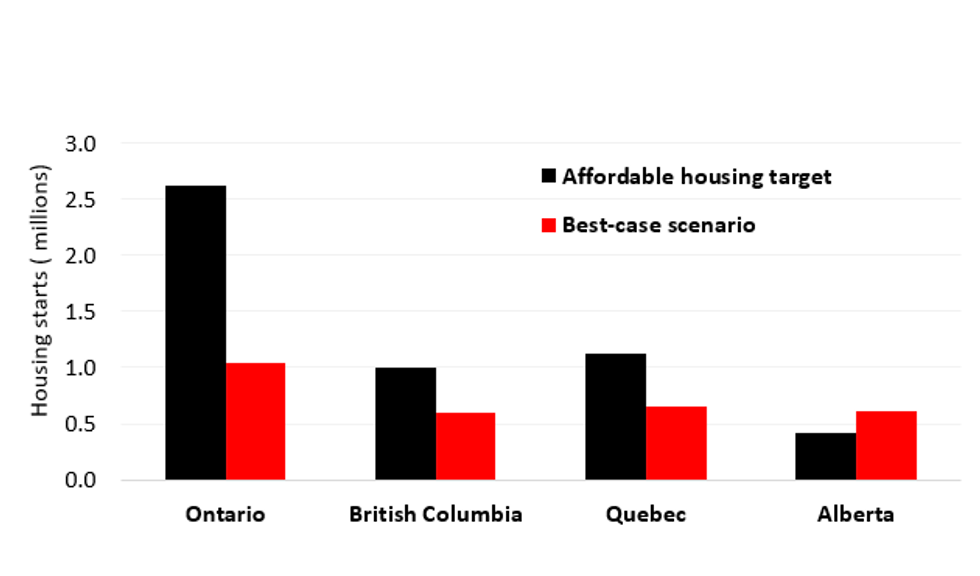

That report found that even in best-case labour scenarios, Ontario, Québec, and British Columbia -- Canada's three most-populous provinces -- will all still fail to meet the 2030 affordable housing targets that the CMHC outlined in a June 2022 housing report. Only Alberta, Canada's fourth-most populated province, would meet its target.

Best-case scenario projections are based on the highest percentage of the population who work in residential construction in the past 25 years, combined with the lowest amount of residential construction workers needed per housing unit. The 2030 affordable housing targets are estimates that the CMHC believes would restore affordability.

Ontario

The CMHC says that Ontario would need to double the number of housing starts under best-case scenarios if they want to reach their 2030 target. They also note that labour shortages are "the most acute" in Ontario and that it's the only province where there are more projected households than forecasted housing starts through 2030. As is always the case, the shortage of supply combined with high demand will inevitably result in higher prices.

Québec

As is the case with Ontario, Québec would also have to double their amount of housing starts in order to meet the 2030 targets. The CMHC projects that the province will have more housing starts than amount of households, however, and that Québec has so far seen less affordability issues because more people rent, rather than buy. Indeed, Statistics Canada data published in September showed that Québec had the lowest homeownership rate in all of Canada.

British Columbia

Likewise, British Columbia would also need to double its amount of housing starts if it wants to meet the 2030 target, and the province is also projected to have more housing starts than new households between now and 2030. However, the CMHC points out that "a phenomenon more prevalent in BC is that some housing starts will be offset by demolitions to make way for more newer units." In BC, because of land shortages and projects such as SkyTrain expansions, pre-existing buildings are often demolished to make way for newer buildings, which are usually more expensive.

Alberta

Alberta is the only province of the four that were examined which could likely meet its 2030 target in a best-case scenario. Elsewhere in the report, the CMHC also points out that Alberta is the only province of the four where labour capacity was not at its maximum in 2021. The CMHC also notes that Alberta is not facing tight market conditions that the three aforementioned provinces are, something Alberta has highlighted in a recent advertising campaign seeking to attract talent into the province.

Affordable Housing and Labour Shortages: Solutions

Aside from pointing out the dire circumstances, the CMHC also proposed several solutions.

The most basic is to "create more incentive to develop a new generation of skilled construction workers." Some of that is already happening. On Thursday, the Province of Ontario announced $3.7M in funding for the construction sector, as a direct action to "combat labour shortages." Over in BC, $21M in funding was announced in late August that would go towards a new construction trade apprenticeship program.

The CMHC says that 2020 and 2021 were "unprecedented" for the Canadian residential construction market, with workers falling ill, lockdowns, and supply chain issues. Companies were forced to get creative in order to complete projects on time and avoid penalties. Oftentimes, those solutions would then fall on the shoulders of workers.

According to the CMHC, the number of workers per residential unit under construction has already been decreasing in recent years, in Ontario, Québec, as well as British Columbia, which means that individual workers are increasingly being asked to do more. That, of course, could then re-contribute towards labour shortages, as workers struggle with the workload or decline those jobs to begin with.

These challenges are then compounded with rising interest rates, creating circumstances where projects will likely be delayed, the housing supply becomes plugged up, and prices rise further due to stable demand, as experts in the industry have previously told STOREYS.

Other solutions the CMHC proposed include further increasing the emphasis on building multi-unit housing, because it has less logistical constraints for labour; further use of federal programs such as the Housing Accelerator Fund and Rapid Housing Initiative; converting existing commercial structures into housing; and more targeted immigration programs with the goal of importing skilled construction trade workers.

"The task of increasing housing construction to reach our 2030 affordability supply targets are huge," the CMHC said. "Ultimately, the private sector in collaboration with municipal, provincial, and federal governments will need to continue to work together to find solutions."