The long-awaited Surrey-Langley SkyTrain expansion project was officially approved last month, and not only was it projected to be completed sooner than expected, in 2028 rather than 2030, it's also expected to cost $500,000 less, due to the project now unfolding in a single phase rather than two.

The 16-km long expansion of the existing Expo Line will include eight new stations and finally allow for a single non-stop train ride from downtown Vancouver all the way to Langley. A big reason why many are excited about the project, and one of the stated motivations behind the project, is that while Surrey has seen more and more development over the last decade, parts of it (and Langley) are still somewhat inaccessible via public transit. This expansion project would finally change that.

There will be some obvious benefits, felt most by residents of the surrounding area, such as new amenities in the area and more convenience. "The project will provide sustainable transportation choices, as well as opportunities for new market and affordable housing, child care and health-care centres, and other public amenities in Surrey and the Fraser Valley", the government said in a news release. Then there are the less obvious benefits.

Transit-Oriented Design

TransLink has been emphasizing "transit-oriented communities" for a long time now. In a 172-page document from 2012 focused just on this topic, TransLink described it as "places that, by their design, allow people to drive less and walk, cycle, and take transit more." "In practice", TransLink said, "this means they concentrate higher-density, mixed-use, human-scale development around frequent transit stops and stations. They also provide well-connected and well-designed networks of streets, creating walking and cycling-friendly communities focused around frequent transit."

TransLink says communities built in this way have proven to be particularly "livable" because they support healthy lifestyles, are "sustainable" because they reduce the need for cars, and "resilient" because they're able to retain their appeal as surroundings or demographics change. When reached for comment by STOREYS, a Senior Public Affairs Officer from the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure pointed to Marine Drive Station as "an existing example of the type of transit-oriented development that will accompany new transit projects."

While Marine Drive Station originally opened in August 2009 as part of the Canada Line, the surrounding $220M Marine Gateway retail hub did not open until 2016. All in all, Marine Gateway consists of 240,000 sq. ft of retail space, 260,000 sq. ft of office space, and enough residential space to house 800 residents.

The idea should be clear. With all that retail, office, and residential space so close together and next to a transit hub, people can very conceivably not have to drive and get everything they need to get done in a day without leaving the area. That's what the government and TransLink have in mind for one of the new Surrey-Langley SkyTrain stations, 196 Street Station, near the municipal boundary between Surrey and Langley. Speaking to STOREYS, the Ministry of Transportation representative confirmed that "the Province, TransLink, City of Surrey, City of Langley and Township of Langley will be doing a transit-oriented development study for the area within 800 meters of the 196 St. Station, to help guide future planning and land-use decisions near this new station."

Housing, Transportation, and Affordability

So what does transit-oriented design have to do with housing affordability? How far you have to get to work, or school -- and specifically how much it costs you -- depends on where you live. That cost, on top of expenditures for housing, makes up the two biggest regular expenditures for most households, and they're usually interrelated. In most cases, the farther you live away from where you work, the more it's going to cost you to get there, and the less income you'll have left over. Transit-oriented development seeks to flip this around, by designing communities where people don't have to travel far to get to where they need to go, so they can spend less on transportation -- via switching from driving to taking public transit, for example -- and have more money left over.

One of the most popular measures of affordability is the Housing + Transportation Affordability Index (H+T Index), created by a US non-profit called the Center for Neighborhood Technology. Traditional financial advice typically recommends that housing cost no more than 30% of your household income. The CNT includes transportation along with housing, and sets the recommended benchmark number at 45%.

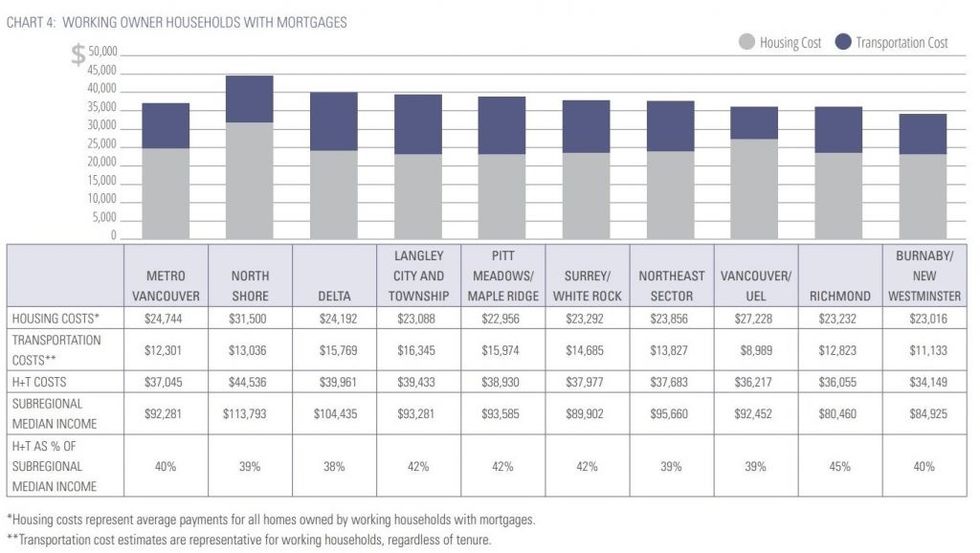

Metro Vancouver's version of the H+T Index was created as part of the Regional Affordable Housing Strategy and is referred to as the Housing and Transportation Cost Burden, and while Metro Vancouver has not said that the CNT's benchmark of 45% carries over well to our side of the border (or set their own benchmark), a 2015 study by Metro Vancouver -- the federation of 21 municipalities, one Electoral Area and one Treaty First Nation -- found that households with a working owner and a mortgage had a H+T cost burden somewhere between 38% to 45%, depending on the region where they lived.

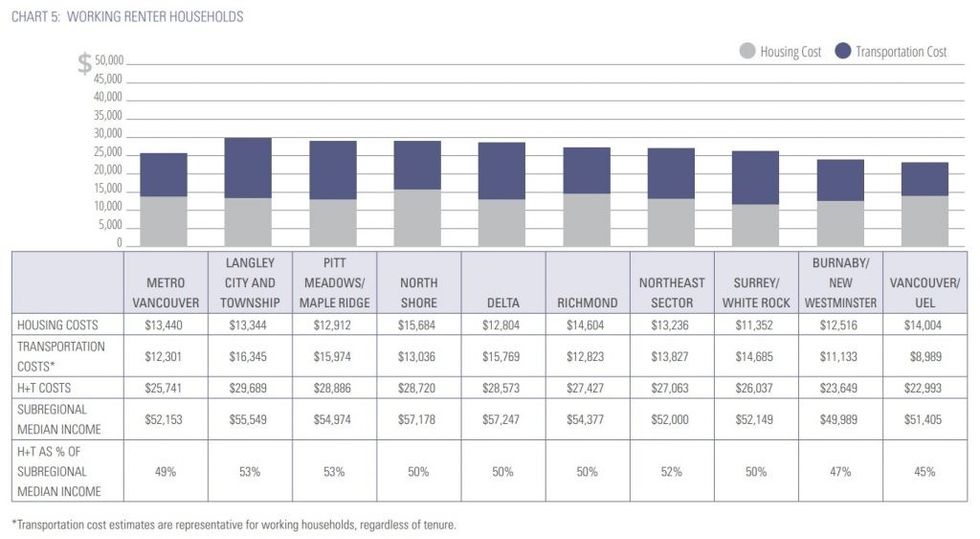

Renter households, however, had a H+T cost burden of at least 45%, with most renters across most regions at over 50%.

According to the report, 35% of all Metro Vancouver households in 2011 were working owner households with a mortgage, while working renters made up 25% of all households. (The remaining were either working owners without a mortgage or non-workers.) However, 2016 census data had the number of renters in Metro Vancouver at over 36%, indicating that the distribution of homeowners and renters has shifted significantly in the other direction, and with house prices in Vancouver steadily increasing over the past few decades, this means more and more people in Metro Vancouver have been forced to come to terms with the city's affordability problem.

The Reality In Vancouver

To alleviate housing costs and stave off Vancouver's notorious reputation of being unaffordable, many new SkyTrain development plans have also included a focus on affordable housing in the areas surrounding new stations.

A 2021 analysis by Infrastructure BC on the now-approved Broadway Subway Project concluded that one of the benefits of the project will be that it will "improve affordability by enabling greater mobility at reduced cost for residents across the region and encouraging transit-oriented urban development and housing availability."

Similarly, in last month's news release announcing the Surrey-Langley SkyTrain expansion, the government said one priority of the project was to include "transit-oriented land use along the Fraser Highway corridor with market and affordable housing policies."

The awareness and intent is there, but there is also evidence that SkyTrain expansion projects are actually counterproductive towards increasing affordable housing.

A 2018 study found that the values of land surrounding a proposed SkyTrain expansion project increases when the project is approved, decreases during construction, and then increases again upon completion.

A study published earlier this year by Bank of Canada economist Dr. Alex Chernoff and Dr. Andrea Craig, a UBC Okanagan economics professor, on the Millennium and Canada Line expansion projects that completed in the aughts also found that those expansions eventually increased housing prices in the surrounding area, as well as housing prices in pre-existing areas connected to the SkyTrain. The latter is explained by an increase in desirability resulting from those neighbourhoods now being connected to even more transit-accessible locations.

Sometimes, affordable housing that's created as part of these projects come at the price of tearing down existing, less expensive rental buildings, as was the case in Burnaby's Metrotown area. Newly developed affordable housing is often also more expensive, by virtue of being new. Before the Broadway Subway Project was even approved, residents of the area protested the project out of concern for these exact issues.

“Public transit infrastructure is often characterized as a government expenditure that improves the welfare of predominantly low-income households", Dr. Craig said. “But by examining years of data spanning the multi-billion-dollar expansion of rapid transit, we estimate that eventually, higher-income households benefit more from this rapid transit expansion than lower-income households.”

It remains to be seen if that will be the case with the Broadway and Surrey-Langley SkyTrain expansions. Different regions have different characteristics, which can mean that the effects of all SkyTrain expansion projects may not all be the same. However, the opposite is also possible: maybe some things just don't change.