In the midst of a housing crisis, rent control, or a lack thereof, could be the difference between going on that yearly vacation or not, and for some, between remaining in your home or relocating to a parent's house, a friend's couch, or even a shelter.

But while tenants certainly benefit from rents being protected against market volatilty, some have argued the protection disincentivizes rental construction and makes operating costs for some landlords economically unfeasible. Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck once said of the policy, “In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city — except for bombing.”

Theatrics aside, it is a divisive topic, and one Ontario legislators can't seem to come to a consensus on.

As it currently stands, rental buildings and units in Ontario constructed and occupied for the first time after November 15, 2018, are not subject to rent control — a policy change brought in by current Ontario Premier Doug Ford soon after being elected. Buildings and units constructed before that date are still protected by rent controls and subject to the provincial guideline for rent increases, which is currently capped at 2.5%.

Ford's decision was just the most recent in a long line of rent control reversals, exemptions, and reintroductions that have been implemented and tested since the protection was first introduced under the National Housing Act in 1944. After the post-War economy recovered, rent control was then reversed in the 50s, brought back in the '70s, modified in 1992 to exempt rentals built after 1991, and briefly consolidated by the Ontario Liberals in 2017 to bring all rentals under the same rent control system again.

More recently, Ontario Liberal Party Leader Bonnie Crombie proposed to bring rent control back in, via a phased-in approach she says will appease tenants, landlords, and developers alike.

When it comes to rent control, the conversation is in constant flux, to say the least. Rent control cuts to the core of how many Ontarians experience housing — so does that make it a right? Or is it a 'destroyer' of cities, like Lindbeck said? Or does it fall somewhere in the middle?

The Benefits And Shortcomings Of Rent Control

To the Co-Chair of the Federation of Metro Tenants' Associations (FMTA), Laura Anonen, the protection is essential. "Rent control is extremely important to renters. It's what protects our rent in a housing crisis that continues to worsen," Anonen tells STOREYS. "With these newer units, there's cases where a landlord will increase the rent by significant amounts. There's no limit, basically, on these units."

And while it's illogical for landlords in newer buildings to increase rents beyond market value, the lack of regulation means they can use financial pressure to unfairly evict unwanted tenants. “We helped with a case a couple years ago, I believe. It was two sisters renting a unit, and the landlord increased the rent by $10,000 a month, which was just a way to get rid of them," says Anonen. "But we work with a lot of people who are lower income and even just $50 can make a difference in their monthly budget," she adds.

Still, advocates for rent control argue that the protection doesn't go far enough. Landlords who own rent-controlled units are still allowed to apply for an Above Guideline Increase with the Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB), for example, and vacancy de-control, which allows landlords to increase rents by however much they want between tenants, has incentivized an increase in 'renovictions' in recent times.

"If you've been in your unit for years and you have low rent, you have a target on your back from your landlord, basically. Because if they can get you to move out, they can double, triple, quadruple their rent," explains Anonen.

The Mismatch Between Rent Control And Rental Ownership Costs

On the other hand, those on the development and operational side of the rental sector say rent control kills builders' pro formas and makes it harder for landlords to cover expenses.

"Rent control is really a way for governments to artificially set prices for a good or product. And in this case that product is rental apartments," President and CEO of the Federation of Rental-housing Providers of Ontario (FRPO) Tony Irwin tells STOREYS. "To me, there's a fundamental disconnect when the government is determining what can be charged for something without taking into account the corresponding costs for that thing. [...] I think we all want to pay less for everything we consume, but obviously there's a cost to produce everything."

Sometimes, Irwin says, it just doesn't pencil. For example, Toronto’s property tax increase for multi-residential buildings will be over 3% next year, while rent increases for rent-controlled buildings is set at 2.5% per year, as opposed to being set to inflation.

“Property taxes are already going up by more than how much rent can be increased by, but that doesn't even take into account any other expenses involved in running a building, from insurance to utilities to maintenance," Irwin explains.

Does Rent Control Disincentivize The Construction Of Rental Units?

Of course, no one is forced into landlordom and owning a rental property is an investment, not a guaranteed profit machine. Nevertheless, there is a dire need for more rental housing in Ontario, and some think rent control disincentivizes investment in the construction of new rental units, which in theory, cuts supply and drives rents up.

In reality, the data is murky, and declines in purpose-built rentals are more likely tied to a perfect storm of economic conditions rather than rent control as a dominant factor.

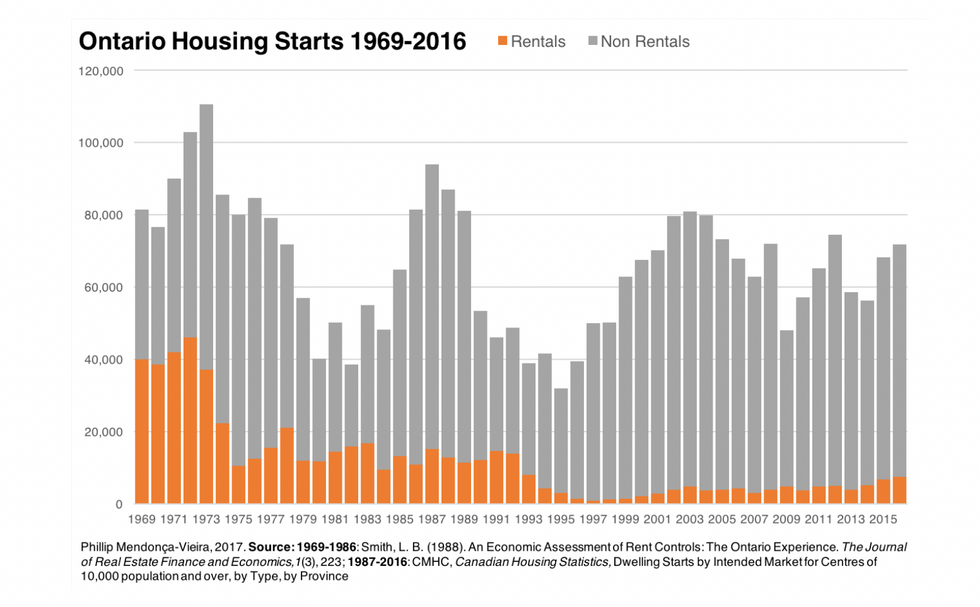

A 2018 study from the FMTA, for example, argues that rent control has historically had a negligible impact on rental housing construction. The study, titled Actually, Rent Control Is Great, found that while the construction of purpose-built housing did wane in the period following the re-introduction of rent controls in the '70s, the expected resurgence when the protection was significantly repealed in the 90s never happened, indicating that rent control is not the primary factor quelling rental construction.

The paper suggests that larger economic forces like interest rates, demographic shifts, and recessions have a bigger role to play. For example, while rental vacancy rates hit an extreme low of 0.1% by 1986, signalling a lack of supply, the paper points out that the mid-80s would have also been when the baby-boom cohort hit the prime rental occupancy age range of 20-35.

That being said, purpose-built rental starts have quadruped over the last decade, but their resurgence is tied to factors like increased demand from historic population growth, would-be homeowners sticking to rentals in the face of unattainable home prices and interest rates, government incentives to build more rental housing, and yes, ballooning rents. Still, the resurgence came over 30 years after rent control on new builds was repealed in 1992.

"[Decline in rental supply] is the excuse economists and real estate agents, people in that sector, use. And, you know, we haven't had vacancy control or proper rent control for years, and we're not seeing more buildings being built either," says FMTA's Anonen. "Clearly, the system is not working. It's getting worse, and it's time to try something different."

Rental Supply And Affordability

Towards the end of 2024 and into 2025, Toronto has seen rent growth start to lag for the first time since 2021, partially due to reductions in immigration, temporary foreign workers, and international students, but also because of a wave of new rental supply coming online.

"Last year's numbers were greater than any time over the last 30 years," Irwin tells STOREYS. "And that is a great illustration of the point that if we do get more supply online, recognizing we need all forms of supply that meet different needs and budgets, building more will help with rents."

But as Irwin alludes to, the type of rental supply coming to market is key. In recent times, many developers have favoured more profitable luxury rental projects in the face of sky high government fees and charges as well as rising costs of land, labor, and construction.

"There is a need for all kinds of housing across the continuum. But the reality is that in Toronto over the last many years, much of the projects that you have seen built and come online have been at very unaffordable rents for most people," says Irwin. "But in terms of why those are the kinds of buildings that have been primarily built in Toronto for the last number of years, it is because that's the only sort of economic scenario that has worked.”

So, under current building conditions, even if rent de-control did foster more development, it can't be the sole solution to the rental affordability crisis.

A Phased-In Approach To Rent Control Could Be The Answer

Bonnie Crombie's More Homes You Can Afford plan, proposed in early-December 2024, could present an equitable alternative. The plan aims to support all parties by introducing phased-in rent control, where, starting from the date on a building’s occupancy permit, new developments will be granted an exemption from the Annual Guideline Increase for a to-be-determined period of time.

"We believe this approach strikes the right balance between providing tenants with predictability and mitigating risks for those who invest in getting more rental housing built," a spokesperson from Bonnie Crombie’s policy team tells STOREYS.

The reform has been tested in places like Manitoba, California, and Oregon and is to be supplemented with other actions that are meant to further boost rental housing supply, including scrapping development charges and exempting purpose-built rental housing from other punitive taxes, such as community benefits charges.

"Doug Ford deliberately chose to expose ‘the little guy’ to arbitrary, indefinite, unlimited year-over-year rent increases," says the spokesperson. "Despite his lofty promises, Ontario's housing starts dropped by almost 18% over the last 12 months; the sharpest decline among all provinces, we are building almost 20,000 fewer homes than we did in 1981 when the interest rate was in double digits and we had roughly half the population, [and] Ontario's rental housing vacancy rate now is at 1.7%."

FRPO's Irwin says the organization is waiting on more details, but is encouraged by Crombie's acknowledgement of the need for more breaks for developers. "If I’m correct, [Crombie] acknowledges that there is a need to have an exemption for new constructions, because that is critical to getting projects built," he says. "They're not condominiums, they’re not selling them out in advance or once you complete the project, so the ability to be exempt from rent control for some period of time is critical to be able to make the economics work on those projects."

- Some Ontario Renters are Facing Unregulated Rent Increases. Here’s Why it's Legal ›

- Ontario Keeps Rent Cap At 2.5% For Third Year To “Protect Tenants” ›

- Average 2-Bed Rent Could Hit $5,600/Month In Toronto By 2032 ›

- Bonnie Crombie's Housing Plan Targets DCs and Land Transfer Tax ›

- Average Rent Hits 18-Month Low, "Improved Affordability" Ahead ›

- GTHA Projects Offering Rental Incentives Doubles In Q1 ›

- Toronto's New Renoviction Bylaw Goes Into Effect Today ›

- Canadian Rent Decline "Compounding" As July Sees 3.6% YoY Drop ›

- Rental Market Drives Canadian Housing Starts To Multi-Year High ›