When the Province introduced Bill 47 in Fall 2023, officially known as the Housing Statutes (Transit-Oriented Areas) Amendment Act, what drew most of the attention were the minimum heights and densities that the legislation set for areas immediately surrounding SkyTrain stations and major bus loops.

Over a year later, local governments have implemented the legislation, but many are still trying to figure out the fine details, such as whether there should be any housing requirements attached to the densities.

What has flown under the radar and has already changed how developers operate is Bill 47's requirement that municipalities remove minimum parking requirements in those TOAs. Minimum parking requirements are typically expressed as a ratio between the amount of parking stalls required per residential unit — a ratio of 0.5 means one parking stall for every two units, for example.

Housing advocates have long pushed for such requirements to be eliminated, both because it encourages more use of public transit and because it contributes to housing development. Last month, the Sightline Institute published a report concluding that parking reform alone can boost homebuilding by 40% to 70%.

Major cities across North America are starting to get the picture. Toronto removed minimum parking requirements in new residential construction in 2021. In addition to what the Province required, Vancouver went a step further last year and removed minimum parking requirements across the city for all uses.

To get a sense of how developers are approaching parking in light of that newfound freedom and flexibility, STOREYS recently spoke to Curtis Neeser, Executive Vice President of Residential Development at Beedie, and Brad Jones, Chief Development Officer at Wesgroup Properties, both of whom have projects near transit and away from it.

Space(s) and Time

"How Beedie is approaching it is really a project-by-project approach," said Neeser. "For example, at Fraser Mills, we're transit-friendly, but not on a transit station. We've spent a lot of time learning and studying the market, and we might have a slightly higher parking ratio there than we would [at] our Moody Centre project in Port Moody where we're 200 metres from the station."

The tenure of the homes is also a factor in determining the amount of parking to provide, with parking demand typically lower for rental buildings than condo buildings. For mixed-use buildings with a commercial component that needs visitor parking, it's also helpful to know that commercial visitor parking is more often used during the day, whereas residential visitor parking is more often used at night, allowing for certain efficiencies.

In terms of costs, Metro Vancouver published some research earlier this month finding that the cost of constructing parking can exceed $200,000 per stall and reach as high as $230,000 in some scenarios.

Neeser says he hasn't personally seen costs get quite that high, but can see it happening in projects where underground parkades go beyond five levels and the soil conditions are poor. Otherwise, costs are generally closer to around $40,000 to $60,000 per stall, but have steadily risen along with general construction costs.

"That is on the higher end, but I would say the higher end is becoming more regular," adds Jones. "It depends on where you're building. There's so many areas in Metro Vancouver where you have challenging soil to build in or you've got high water tables, so you're putting parking in ground water. With city requirements over the last few years, it's generally getting to the point where you have to have a full cut-off wall to manage ground water, and so that's where you're getting into the high end of those costs."

Construction goes from the ground up, but in most cases it actually starts from below ground and the underground parkade. Jones says a full cut-off wall made of concrete and steel around the perimeter of a site can go 80 to 120 feet deep and can sometimes take six or more months to construct. As with all costs, it's not only the cost itself developers have to worry about, but also the financing involved.

"It's not only the cost, it's also the carry and the construction debt," said Jones. "Time is a big consideration in these underground parkades, too. How long does it take to dig to the bottom of the hole? How long does it take to get out of the ground? A typical 25- or 30-storey tower, assuming you've got plus or minus 200 stalls of parking, you're probably looking at about a year to go down and up and get to grade. And you're financing that. Interest rates are coming down, but if that year all of a sudden becomes a year-and-a-half, you're financing that cost, too."

Parking Infrastructure

Like housing, parking also has certain infrastructure needs, and increasingly so as the popularity of electric vehicles continues to surge. As EV popularity has increased, so have the costs for developers.

"The market is demanding [EV charging] to an extent, but not to the extent that it's being required," said Jones. "The bigger cost isn't so much putting it in the building, it's the demand on the electrical grid that it's creating. On many projects, it's triggering electrical upgrades — off-site, beyond our project — in the community that we end up having to pay for."

Jones says he recently got into a friendly debate on LinkedIn about how much the EV charging industry has benefited from housing development, which Jones believes to be a lot.

"Housing is actually supporting your entire industry," Jones said in a back and forth on LinkedIn. "When Tesla sells a vehicle, they're not paying for the significant cost of the electrical infrastructure upgrade that's required in communities to support those vehicles. New housing is. And depending on where you are and what the grid is, the neighbourhood, and what the limitations are, it can be significant, significant costs. Sometimes in the millions of dollars."

The popularity of EVs, however, has also resulted in improved technology, which has helped developers.

"The technology and the rationale has caught up," said Neeser. "What I mean by that is the load-sharing aspect of electrification. If we go back to the early days of EV stalls, some municipalities needed dedicated EV chargers per stall, or one out of every four, or whatever it was. That then means your electrical room and the dedicated load to those stalls were much larger. But if you can do a load-sharing management plan, it helps with that and electrical rooms don't have to grow as much as they once would have."

A big part of construction is efficiency and making the most efficient use of the space you have to work with, and more requirements generally decrease that efficiency.

"Regulations around increased bike parking — that takes up a larger footprint, and physically the bike parking has to be near or at grade, otherwise you have put in a dedicated bike elevator in," said Neeser. "That has a cost associated with it and it means you're just going down deeper into the ground to provide the same parking stalls you would have otherwise been providing."

The Province is also set to introduce an update to the BC Building Code that requires 100% of units in new residential buildings to meet accesssibility / adaptability requirements. Prior to the Province delaying the change to March 2027, developers STOREYS spoke to were extremely concerned about the changes and the sigificant costs they would bring, all of which can be summed up as decreasing the efficiency of buildings. Some were also concerned that making 100% of units accessible would mean parking stalls also have to be accessible (wider), which would further impact efficiency.

TDM Contributions

In lieu of providing the required amount of parking, most local governments have policies — around "transportation demand management" (TDM) — that require developers to make transportation-related contributions in other ways, whether it be subsidizing transit passes for residents, including bicycle facilities, or providing car sharing on-site. For developers, it then becomes about finding the right balance between TDM contributions and how much parking to provide.

"I'll use our Port Moody project as an example just because we're working through it right now," said Neeser, from Beedie. "We're going to be providing transit passes to encourage use of transit, and we're also on the West Coast Express there, so there's a lot of great transit options for future residences there. We're focused on bike parking and residents having secured lockers so it's not just a big room of bikes. Then we have the car share model. So what we're trying to do is create a lot of flexibility and optionality for residents."

On the car share front, Neeser of Beedie adds that he has seen situations where car share requirements they have with local governments are tied to a particular car share company that then later goes out of business (Car2Go), adding that he thinks local governments should allow for more flexibility. Jones agrees.

"Different municipalities all handle it slightly differently, but it can get really expensive," said Jones. "There's often requirements for car sharing spaces, but that's complex. Evo is probably the biggest one, but they don't put their cars in mixed-use residential buildings, so sometimes we're required to buy a car from a car share company, but sometimes the car share companies don't even want the vehicles [there] because their usage rates are so low."

Regarding subsidizing transit passes, Jones questions whether it's fair to ask developers to do that considering new development projects are already subject to a development cost charge (DCC) that goes to TransLink.

"The costs of the transit passes is really, really expensive. All of these projects are paying a TransLink DCC to support transit growth and operating costs, or wherever it goes to, and then on top of that we're paying for people's usage of transit. That can, at times, be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars as well."

Next Level Parking

What about parking above ground?

It's a pretty common occurrence in places like Kelowna, but residential towers with multi-level parkades above ground are much less common in Metro Vancouver. Less common, but not unheard of, and it's something developers are increasingly considering.

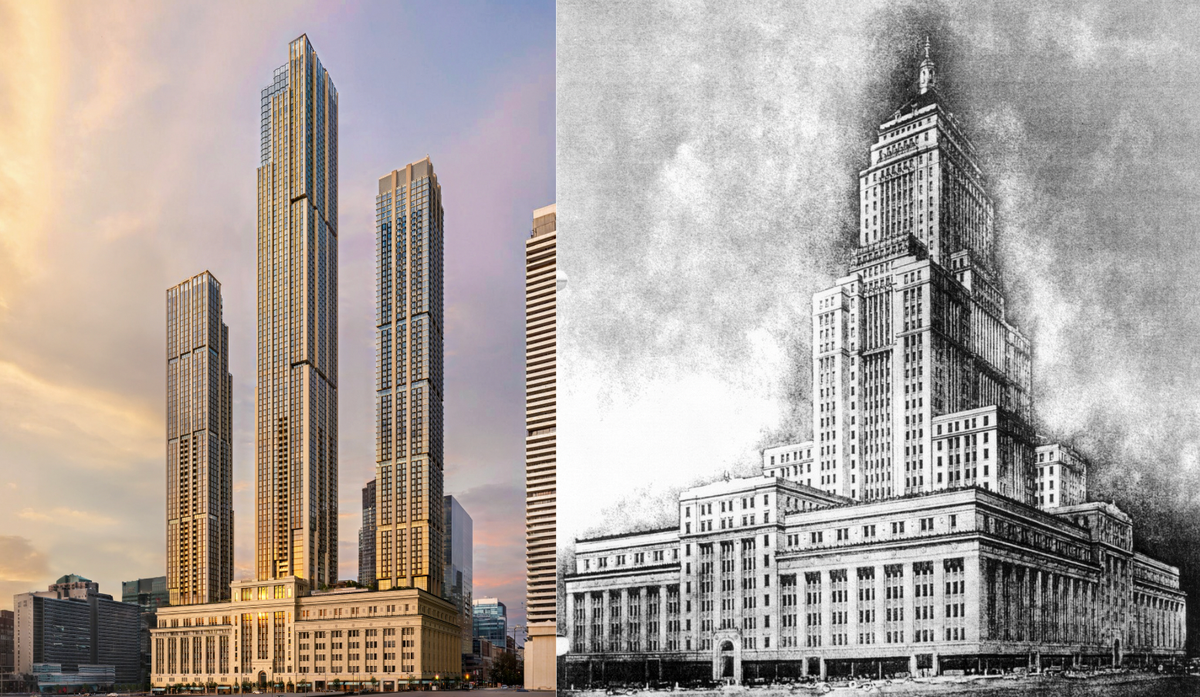

At the aforementioned Fraser Mills in Coquitlam, the first high-rise tower Beedie is developing, the 36-storey Debut, is set to include a four-level parkade with 376 vehicle stalls and 433 bicycle stalls above ground. The parkade will be wrapped with townhouses around the perimeter, while the roof will be used as an amenity space.

Part of the reason for that decision is the site's proximity to the Fraser River floodplain, but another reason is the costs, which Neeser says would have been considerably more had they opted to go underground.

Jones says Wesgroup has also been talking to local governments about above-grade parkades that would be similarly wrapped with residential or retail.

"What we've discovered as we've been going down this path is there's a massive reduction in carbon," Jones said. "If we were to not build that cut-off wall and not excavate a parkade that's four or five storeys deep, it actually works out to be like a 40% reduction in carbon in the building. The cut-off wall is using five Olympic swimming pools of concrete, by volume, and a whole bunch of steel, and 3,000 to 4,000 dump-truck trips for the excavation. It's really expensive and it's really carbon-intensive. If we didn't have to do that, we'd also save likely a year on construction time, so that's a year that housing gets built faster and it's a year of less staff, construction, interest on our loans, and neighbourhood disruption. The cost saving is really really significant."

All of this is to say that costs are like parkades: they can sometimes appear to be endless.