The fight against the Metro Vancouver Regional District (MVRD) and its proposed development cost charge increases has found a second wind, with a group of prominent developers banding together in a campaign against the proposed increases.

Similar to those charged by municipal governments, Metro Vancouver collects development cost charges (DCCs) on new construction projects, which it then uses to pay for new infrastructure — utilities, sewage, solid waste — the region needs to support its growth.

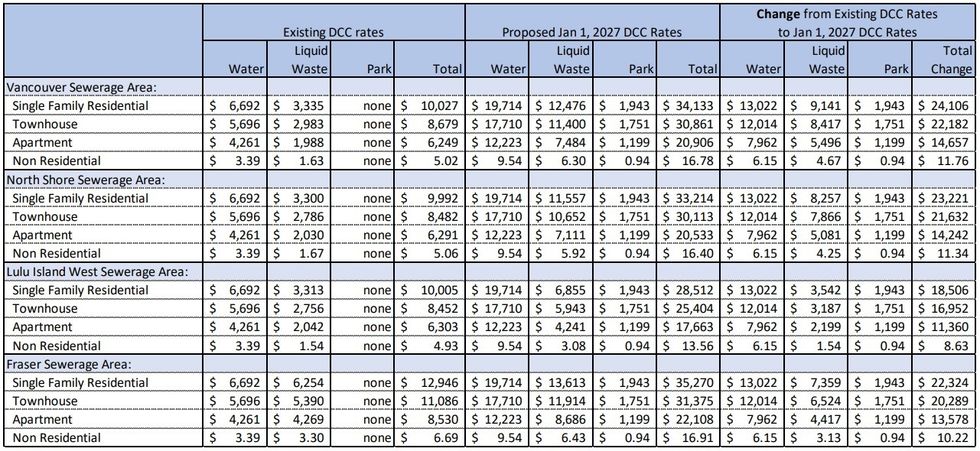

Around this time last year, it was revealed that the MVRD was planning to more than double — even triple, in some cases — its Water DCC and Liquid Waste DCC rates, in addition to introducing a new Parkland Acquisition DCC. The proposed changes drew national attention after Minister of Housing, Infrastructure, and Communities Sean Fraser suspended Housing Accelerator Fund announcements for Burnaby and Surrey over their introduction.

Nonetheless, Metro Vancouver, which has been plagued with cost overruns in recent years, approved the increases, but capitulated some by agreeing to implement the increases across three years, beginning on January 1, 2025. Things cooled down, Burnaby and Surrey received their funding, and the attention of the industry shifted over to the suite of legislation the Province introduced.

On Monday, however, Beau Jarvis, President of Wesgroup Properties — the developer behind the River District in Vancouver and upcoming Civic District in Surrey — restarted the discussion with a three-page letter addressed to the MVRD Board of Directors and emailed to city councillors from across the region, Sean Fraser, Ravi Kahlon, David Eby, and a group of reporters.

"Housing starts in Metro Vancouver have plummeted, dropping by over 20% year-over-year in the first half of 2024 according to CMHC," wrote Jarvis. "In addition, many multi-family projects are not moving ahead. Pre-sales for projects in the first half of 2024 are 29% below the average of the past 10 years and of the 8,593 units released, only 1/3 have been pre-sold signalling that many of these projects won't move ahead as they may not hit a financing test to meet the requirements of the Real Estate Development [Marketing] Act."

"To illustrate this point, in the City of Vancouver there are 14,600 units which have an approved Rezoning or Development Permit that have not started construction," added Jarvis. In Surrey, there are 34,000 units approved and not yet built. The viability of these projects is questionable given the Metro Vancouver DCC increases were not known at the time of the application. There are also 48 projects in Court Ordered Sale, CCAA, Foreclosure or Receivership in Metro Vancouver. An additional 10 projects are notably not moving ahead, which means over 10,000 proposed housing units in Metro Vancouver are not proceeding due to viability issues."

Jarvis attributes these difficulties to rising costs and tougher economic conditions, adding that the difficulties will only be made worse by Metro Vancouver's DCC increases, resulting in limited new supply of housing that will drive up prices further.

Shortly after Jarvis sent out his letter, similar letters were sent out by CEO of Edgar Development Peter Edgar, Executive Vice President of Polygon Homes Robert Bruno, Executive Vice President of Development at Anthem Properties Rob Blackwell, and CEO of Strand Development Mike MacKay.

All of the letters voiced the same concerns and the similarities between the letters — chunks of each are word-for-word identical — were likely intended to show their unity. The letters are also addressed to Mayor of Burnaby Mike Hurley, who took over as Chair of the Metro Vancouver Board of Directors this summer after George Harvie, Mayor of Delta, was removed from the position by his own councillors.

At the core of Jarvis' letter is four asks, which were reiterated by the rest of the group:

- Implement a 2-year delay of the implementation of this fee increase to allow in-stream projects already facing viability challenges to move ahead.

- Implement a revised implementation plan for DCC's where the charges are paid at the end of the project.

- Conduct further financial analysis to truly understand the impact of this increase on land value, development viability on all types of projects and the impact on community amenity contribution funding to member municipalities. Following that analysis, establish an appropriate assist factor to allocate these costs fairly between new development and the existing tax base.

- Engage in meaningful conversations with the industry to implement proper in-stream protection-from the time of Rezoning Application to the end of the project, including a 5-10 year phase in duration.

Jarvis concludes his letter with a request to speak at the Metro Vancouver board meeting on Friday, September 27 and then again at a later Finance Committee meeting.

In an email to STOREYS, Jarvis called the effort a "coordinated push", and it is one that has large similarities to a group of Ontario developers that formed a coalition in August against DCCs. Their campaign, however, has gone a step farther, with the developers pledging to cut the prices of their homes by the same amount governments cut from their fees, dollar for dollar.

Once a topic only those within the industry talked about, the issue of development charges — often described as a tax on new housing construction, in essence — has gained substantial awareness in recent years. With some variances, it's now estimated that approximately 30% of project budgets go towards fees charged by governments — which also include CAC's and BC's newly-created ACCs — that then get passed on to end users.

For governments, it's likely not lost on them these fees worsen housing affordability, but many are strapped for money and reluctant to consider the biggest alternative to taxing new construction: raising property taxes. As such, the debate over DCCs has been framed around who should pay for new infrastructure: new buyers ("growth pays for growth," as this camp calls it) or all residents.

Whether it's "growth pays for growth" or "dollar for dollar," let's just hope the fight over DCCs doesn't get to the point of "an eye for an eye."

- Bosa Properties Says Burnaby Policies Make Purpose-Built Rental Projects "Unbuildable" ›

- Anthem, Polygon, And Canderel Voice "Deep Concern" Over Burnaby's New ACCs ›

- High Vancouver Land Costs Pushing Condo Projects To Suburbs ›

- Strand Revises Project In Vancouver, Partners With BC Housing In Coquitlam ›

- Metro Vancouver To Receive $250M From Feds For Iona Wastewater Plant ›

- Burnaby Approves Polygon's 4-Tower Emerald Place Project ›

- Vancouver Proposing Suite Of Changes To DCLs And CACs ›