In a perpetually under supplied housing market, the narrative across Canada is that we need to “get shovels in the ground” and build – now (or yesterday, frankly).

However, this isn’t exactly resulting in a flurry of action and activity. The construction industry has had a rough road as of late, thanks to everything from supply chain issues and labour shortages, to sky-high interest rates. But restrictive regulations aren’t helping the situation for anyone.

In short, Canada isn’t living up to its construction capacity, according to a new report from the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). In the report, written by Mathieu Laberge, Senior Vice-President, Housing Economics and Insights at CMHC, the resonating theme is that Canada has the construction resources it needs, yet homes aren’t getting built as quickly as they could – and a “fragmented” construction industry isn’t helping.

As Laberge highlights, while labour shortages remain a barrier to increasing supply, roughly 650,000 workers were building homes in Canada in 2023 – the most the country has ever seen(!). However, the construction activity didn’t keep pace with growth in dedicated resources in the country.

“With the current resources, we should be building between 130,000 and 225,000 more homes each year,” writes Laberge. “This equates to an annual pace of more than 400,000 starts per year.” He says that reaching this potential will require long-term structural change. While Laberge acknowledges that the Canadian construction industry has made changes to help move the needle in this direction – including regulations at the municipal level – he says that more “can and must” be done by the government and the industry to increase productivity in the building of new homes.

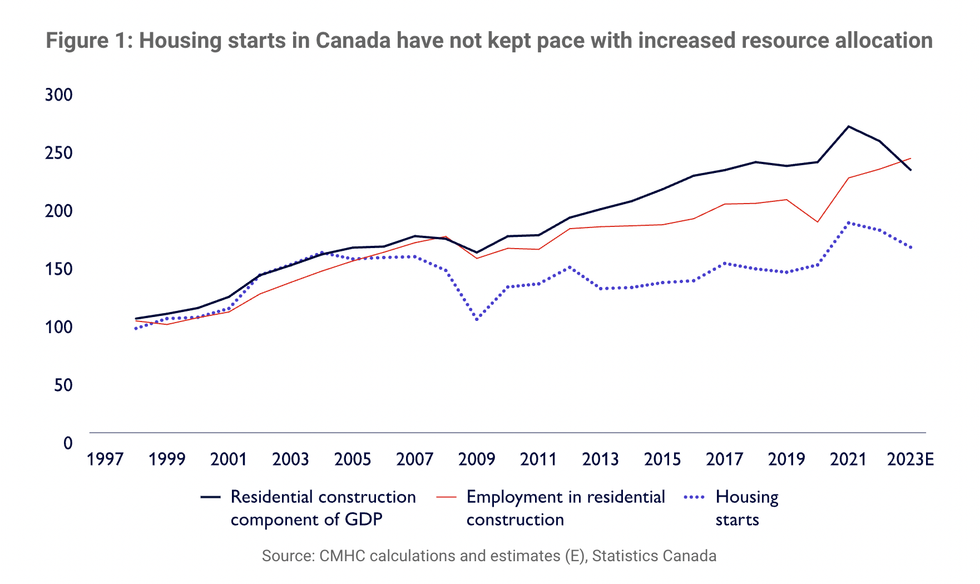

Laberge highlights how, until the mid-2000s, housing starts were closely aligned with employment and gross domestic product (GDP) in residential construction. The years since have seen increased investment in residential construction through both funding and labour, but the pace of construction did not keep up, the report notes.

CMHC looked at different ways to analyze Canada’s potential in housing starts production. According to their estimates, starts in 2023 were far behind potential. According to CMHC, there were 240,267 housing starts in Canada in 2023. However, according to their analysis, a rough estimate puts the potential for annual housing production at the aforementioned target of 400,000 new homes.

First, CMHC researchers looked at the average number of workers needed for each housing unit started. “This can be seen as an estimated measure of labour productivity in the residential construction industry,” writes Laberge. That stats reveal that, from 1999 to 2004, workers per housing starts were much lower than current numbers. This implies that productivity was higher 20 to 25 years ago.

CMHC’s estimate that the country’s housing starts could have reached nearly 400,000 in 2023 is about 70% higher than the total number of units started that year. CMHC said it used current industry employment levels and assumed past productivity levels could be achieved.

Laberge points to CMHC’s most recent Housing Supply Report, which revealed that the ratio of housing starts to population differed dramatically across Canadian Census Metropolitan areas (CMAs), by a factor of two or more. They looked at starts per population in Calgary, Edmonton, and Vancouver – cities that have historically seen a higher ration of housing starts. “This approach assumes that housing preferences and situations are fairly consistent across the country, in theory,” writes Laberge. “Other factors, such as economic context, industrial organization ,and regulations could influence this ratio differently across cities.”

According to CMHC, if housing starts across Canada mirrored the best performing markets last year, added supply would have been close to 430,000 new units. But that obviously didn’t happen. And local regulations are to blame, says Laberge.

“The discrepancy in housing starts production relative to population across Canadian cities hints that regulation plays a significant role in whether building activity can accelerate — especially municipal regulation,” writes Laberge. “Consider the time it takes for things like permit delivery, regulations around how many storeys and units a building can contain, development charges (some are regulated at local and regional levels). This is just to name a few, there are many others.”

Laberge points to CMHC’s 2022 municipal and land regulation survey, which revealed that Toronto and Vancouver had heightened land use and regulatory constraints, while Alberta had more flexible regulation. With that said, Laberge says that British Columbia has since created flexibilities in regulations to be implemented by municipalities, something that signals “a clear desire for improvement.”

On the good news front, Laberge highlights the federal government’s new Housing Accelerator Fund. The program is intended to fund municipal regulatory change to accelerate housing construction. According to Laberge, this has resulted in agreements with 179 municipalities. Furthermore, Laberge says that Canada’s Housing Plan recently added additional funding that will result in more agreements across the country.

But the feds can’t pull all the weight. Laberge says that regulation at the provincial level is also playing a key role in getting those shovels in the ground faster. “For example, the Quebec Government is working towards fostering more flexibility in how different construction trades are hired on building projects, to increase residential construction activity.”

In what he calls the “elephant in the room,” Laberge illustrates that Canada’s residential construction industry is highly fragmented. Across the country, nearly 69% of construction businesses have fewer than five employees, with only one Canadian company having more than 500 employees.

“Consolidation may help generate economies of scale, making the math work better to build affordable housing and enabling some production savings to be passed on to Canadians,” writes Laberge. “For years, the residential construction industry pointed to regulation as the most significant constraint to building more houses. Evidence shows that progress can indeed be made on that front, and all levels of government are adapting, but more must be done.”

Laberge calls for a discussion about how municipal and provincial regulation can help the scaling of housing development in Canada: “A significant dialogue needs to occur on what employers, trades unions and employees in the residential construction industry are ready to contribute in terms of scaling up housing starts and getting Canada to its full potential, in exchange for greater regulatory flexibility.”

In the meantime, new stats reveal that March saw a notable drop in building permits across the country.