The Canadian population hit the 40M mark on Friday, and at the same time, housing supply has plainly not kept pace. A new report from CIBC Economics delves into the particulars of Canada’s housing shortfall, saying that while there is some debate on its extent, there’s no denying that the situation requires immediate attention.

“Guesstimating the size of the housing shortage in Canada is rapidly becoming a national sport. There is no shortage of estimates using different methodologies and assumptions,” writes Benjamin Tal, Deputy Chief Economist at CIBC. “The reality is that there is no one correct number. It really depends on what you are trying to measure. But what is common to all those estimates is that they are all big.”

Tal points to a report from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, released last summer, which estimates that the country will need 3.5 million additional housing units by 2030 to restore affordability.

“The real gap is even larger, as official figures (upon which those estimates are based on) grossly undercount housing demand by students and non-permanent residents, as we have illustrated in previous research. The gap is growing with every day that passes without meaningful action.”

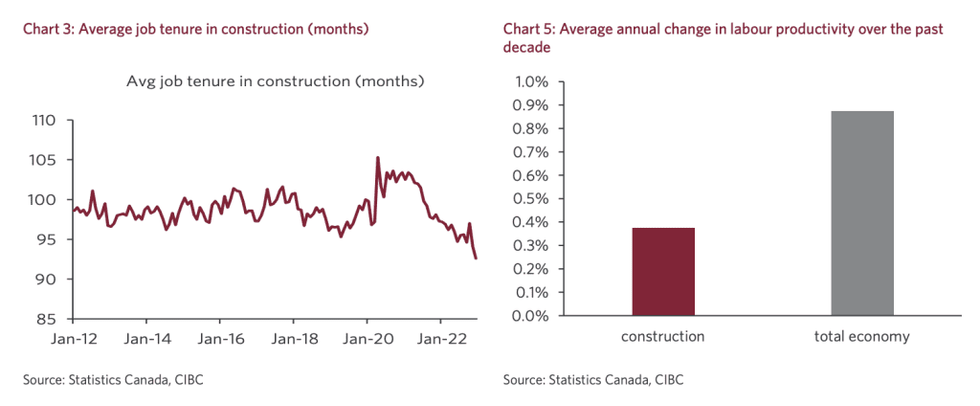

What’s more, Tal continues, Canada is facing a staggering construction labour shortage -- the average number of workers per unit under construction has fallen from six to four over the past decade -- which is undoubtedly hindering housing production.

“Ask any developer about supply issues and the availability of labour usually tops the list,” he says. “And there is no shortage of statistical evidence of that shortage. With no less than 80,000 vacancies in the industry, the vacancy rate is at a record high and a full percentage point above the national average.”

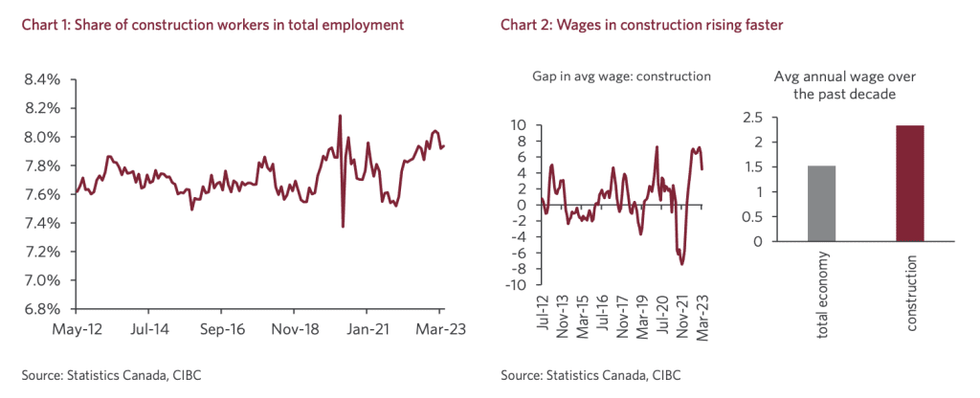

Breaking down the unanswered demand for labour, Tal says that more than half is for specialty trades contractors. This is reflected in wages. More specifically, average wages in construction have escalated faster than in the economy as a whole, which is indicative of the “improved bargaining power of labour in the industry.”

As well, average tenure in the construction sector has sunk to a record low, and this is attributed to “an increased willingness among workers to jump ship in search of higher compensation or better working conditions.” This is in addition to the increasing reality that construction companies are more likely to rely on new, untrained labour, which is both a safety and efficiency issue.

Another by-product of the shrinking labour force is that projects are taking much longer to complete, with project timelines stretching to over 25 months in 2022.

Labour shortfalls are poised to only get worse, says Tal, noting that the share of construction workers over the age of 55 has reached a record high.

“And given that the average retirement age in construction is notably lower than what’s seen in the rest of the economy, the demographic issue is much more pronounced,” he adds. “Based on the age distribution in the construction industry, we estimate that no fewer than 300K construction workers will retire in the coming decade. At the same time, even if we assume no acceleration in residential investment activity from the pace seen over the past decade, the already sizeable labour shortage will grow by additional 60K positions by 2033.”

Acknowledging these realities, Tal calls on all levels of government to step up recruitment strategies in Tuesday’s report.

“The industry is in desperate need of workers -- mostly skilled trades. The obvious sources of labour are domestic training institutions, new immigrants, and foreign workers.”

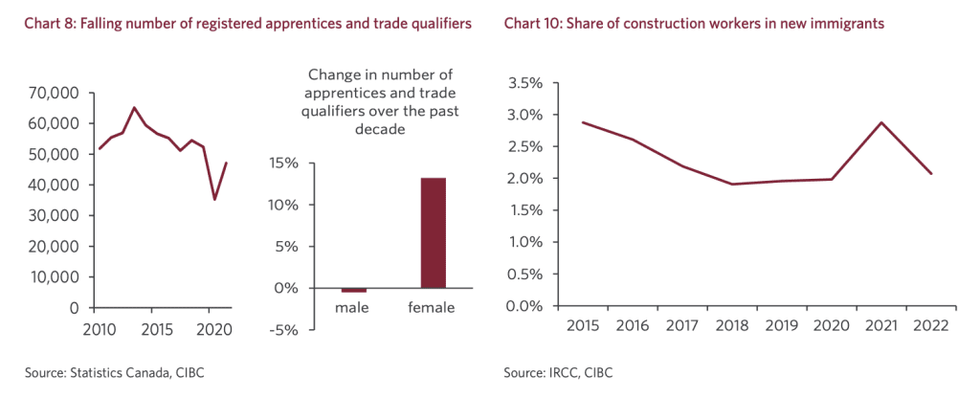

However, the current status quo doesn’t bode particularly well, with the number of registered apprentices and trade qualifiers down 15% over the past decade. Meanwhile, the share of new immigrants in construction is nominal, at just 2%.

On a more encouraging note, the number of women in the field is on the rise. That said, women are still “grossly under-utilized,” notes Tal, accounting for only 7% of the total number of apprentices and trade qualifiers.

“We have to find ways to build on the current positive trend seen amongst women in skilled trades, and we have to reverse the negative trend seen in apprenticeships, while using the tax system as a tool. As an example, the recently introduced tax refund program to skilled trades in Nova Scotia is a step in the right direction,” concludes Tal.

“The recent inclusion of skilled trades occupations in the express entry program is a welcome development, but much more needs to be done. This includes making changes to the immigration points system in order to increase the contribution of new immigrants to easing the severe shortage in construction labour in Canada.”