Ramping up the speed of new builds is on everyone’s agenda – from Prime Minister Trudeau, to local politicians, urban planners, developers, and those in the construction industry. Though they may propose slightly different tactics, their strategies and suggestions remain the same: diversify housing stock (with things like more "missing middle" projects), cut red tape that slows development application approval times, simplify rezoning, and turn to alternative building forms.

The common theme is getting “more shovels in the ground” faster, as they say. But the problem is that we need people to operate these shovels. Currently, Canada’s construction industry is facing a capacity crisis that's no match for the demand.

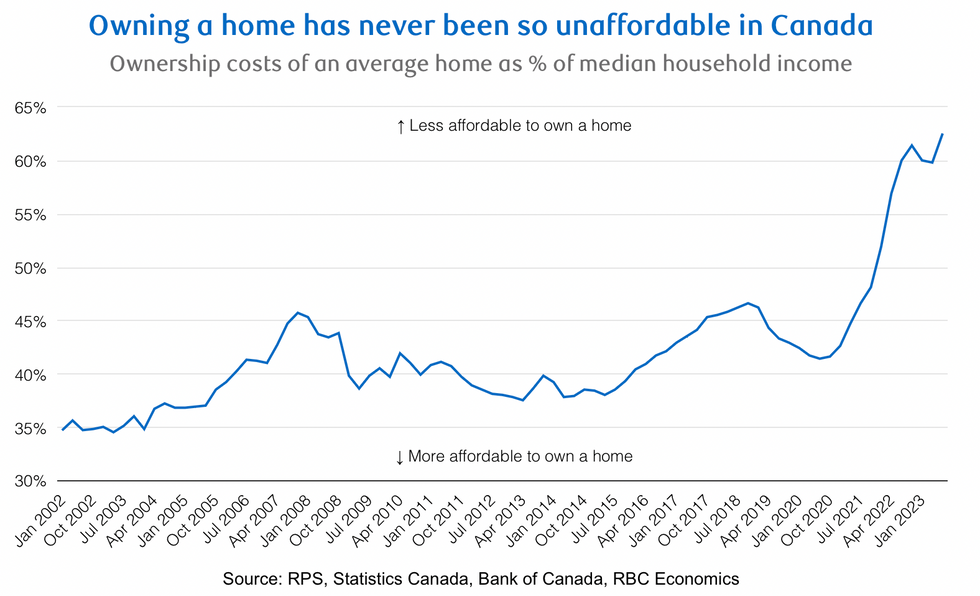

In a, frankly, dismal report released yesterday by RBC Economics, economist Robert Hogue basically said that – unless major changes are made – Canada’s housing crisis is just going to get worse.

The bottom line is that the country needs to produce about 320,000 housing units annually from now until 2030 just to meet the new demand over that timeframe, says RBC. This means that the pace of housing construction would need to jump by nearly half in Canada just to meet future demographic growth, according to the report. “Higher deliveries would need to happen in the near term given our expectation for peak population growth in 2023-2024,” writes Hogue.

This poses a major challenge (and that’s a total understatement). The level of housing production needed is far above anything ever achieved in Canada, says Hogue. The all-time peak for completions was 257,000 in 1974. “The 47% increase needed from recent levels would seriously conflict with production capacity limits,” writes Hogue. “Much of it has to do with labour constraints. Builders already struggle to attract and retain workers. The job vacancy rate in the construction sector (5.1% in Q3 2023) is among the highest across Canadian industries. This could be difficult to resolve over the longer term.”

With that said, the first of seven recommendations outlined by Hogue targets Canada’s construction industry. He says it's important to “aggressively expand” the construction sector’s labour pool to match the need. In fact, according to Hogue, Canada could need more than 500,000 additional construction workers on average to build all homes needed between now and 2030. If that seems ambitious, Hogue says we’ll need even more than that in the short-term to meet peak growth in demand.

“All avenues should be pursued to get more people working in the sector,’ writes Hogue.

While some critics have pointed to immigration as exasperating Canada’s housing crisis – especially in pricey and supply-strapped cities like Toronto and Vancouver – they can also offer a valuable way to help solve it. Hogue recommends that Canada prioritize construction skills among new immigrants. “Canada should materially expand the Federal Skilled Trades Program, allocate more points to qualified candidates in the program based on labour market needs, and fast track candidates endorsed by employers,” writes Hogue.

Hogue said that provinces should follow the same agenda in nominee programs and recognize credentials from other jurisdictions. He also encourages the federal immigration department to maintain a dialogue with the construction industry to ensure immigration programs address structural shortages in skilled trades.

“Immigrants working in construction tend to earn above-average wages, establish themselves faster, and rely on social programs less than other immigrants,” writes Hogue, noting that recent immigrants are under-represented in the construction labour force. The figures say it all: Immigrants with an apprenticeship certificate and non-apprenticeable trades certificate represented just 2.4% of landed immigrants between 2016 and 2021. That’s down from 9.6% during the 1980s.

The problem, says Hogue, is that Canada’s current immigration programs tend to prioritize university education and language skills – something that comes at the detriment of industries that don’t require those, like skilled trades. “Canada must realign its immigration system by refocusing on the mismatch of skills and long-term labour market needs,” writes Hogue.

The country also must do more to make trade schools more attractive to future workers, says Hogue. He recommends setting ambitious targets for skilled trade school enrolment. “Provinces must reverse the decades-long decline,” writes Hogue. “Promotional campaigns run with the industry should attract a new generation of skilled workers, including women, indigenous people, and other under-represented groups. The industry should effectively showcase rewarding careers in skilled trades to high school students and partner with career counsellors to identify good candidates.”

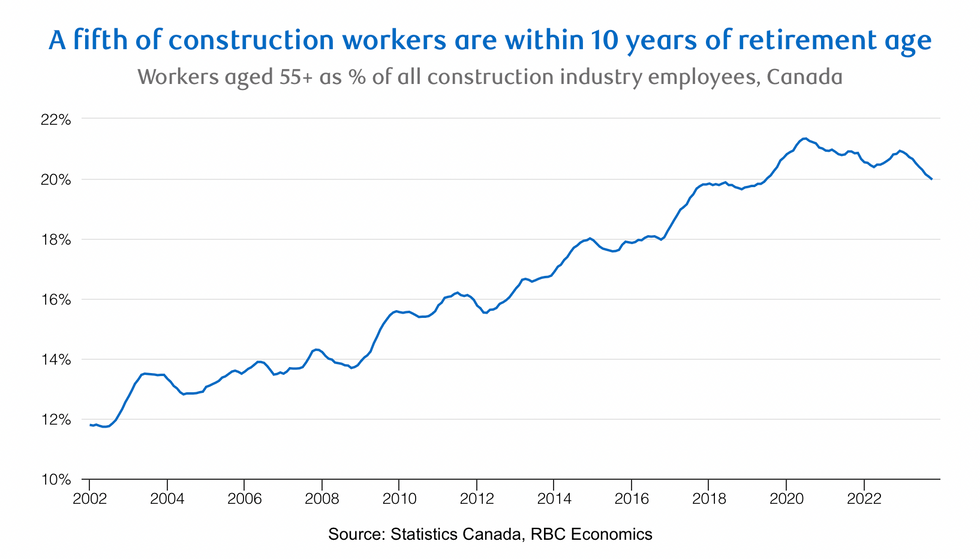

It’s no secret that the Canadian construction industry is filled with aging workers, and that’s perpetuating the labour shortage. One in five construction workers are at or will reach retirement age within the next 10 years. This represents 330,000 workers to replace if they do retire, making it that much harder to expand the sector’s production capacity. Hogue recommends incentivizing aging construction workers to stay on the job longer. “Employers should consider offering special benefits or work arrangements to slow down the flow of retiring workers,” he writes.

Six other recommendations include developing and adopting innovative designs, building techniques and technology; speeding up project approvals; easing zoning restrictions to make a more productive use of land; lowering the cost of building new housing; changing the mix of housing being built; and expanding the housing stock from within.

The full report is available here (read at your own discretion).