In terms of urban planning, this is not Vancouver’s finest hour, according to the internationally celebrated planner behind “Vancouverism.”

Vancouver’s former planning chief Larry Beasley had choice words for the current planning process at City Hall Wednesday night, part of a two-hour talk on view cones, alongside high-profile architect Peter Busby, who’s also globally recognized. It was the latest talk in the ongoing Simon Fraser University City Conversations series. (You can watch the full conversation here.)

Beasley started by talking about the importance of the views, and maintaining relationships with developers who’d cooperated with the protection of them for the last 34 years – while building hundreds of buildings.

“And not say now, ‘well, this one developer can now ruin it for everyone and also ruin it for the hundreds of people all along the corridors... as well as the public,” said Beasley.

Beasley said the key role that the city’s planning staff should provide is analysis and thorough public engagement to ensure that major City Council decisions aren’t motivated by satisfying the individual interests of developers. He also said that without those authoritative planners demonstrating leadership, the public would have to get more vocal.

“Yes, the political bias was there, it is there from time to time,” he said, referring to his own tenure as co-director of planning, “but that is nicely balanced when you have a strong planning department that, No. 1, can appeal to the public and No. 2, can bring things to the attention of Council they may not have thought about,” said Beasley.

“And that’s what is maybe not there now,” he said.

“The planning department is not as strong as it was in those years, and that means you, as the public, have to be strong,” Beasley told the audience.

As for the potential loss of view cones, he wondered if the thousands of residents who’d be impacted even understand what is at stake.

“Many of them don't even realize that what might happen is they would lose that that view, that peek-a-boo that they've enjoyed.

“Unfortunately, we don't have a permanent director of planning right now,” he said, referring to Theresa O’Donnell’s recent departure. “We have a very good temporary director of planning, but we don't have the power and prowess of a permanent director of planning.

“And so I'm anxious that the quality of that analysis may suffer simply because the judgments about the individual parts of it will be more political than technical. If Peter Busby was brought in to do the study I’d be much happier.”

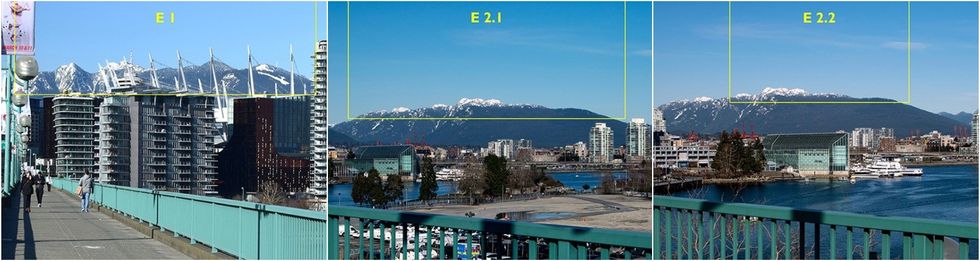

The topic of discussion was the City’s current review of the 1989 first-of-its-kind view cone policy, which protects several view corridors that allow residents to see mountains and ocean, and which has restricted building height and massing over the years. Beasley and Busby were key to the development of the original policy, an idea aimed at protecting the city’s famously beautiful natural environment as skyscrapers started to spring up on the downtown peninsula. During his time as co-director of planning, alongside Ann McAfee, Vancouver enjoyed a golden period in planning prior to the 2010 Olympics that became dubbed “Vancouverism.” In 2019, Beasley published a book of the same title.

Planners around the world took note of the city’s successful liveability and walkability, best identified by downtown’s slender towers atop podiums of townhouses and retail space. And geographical context — and views — played a key role in Vancouverism.

This isn’t the first time that the City has been under pressure to remove view cones.

After Beasley moved on, there was a review of the policy in 2009, under then director of planning Brent Toderian, who was in attendance Wednesday and spoke from the audience.

“There was massive political pressure in 2009 to get rid of the view corridors — the pressure was from developers and from their architects, who actually were saying to me and my staff, ‘people don't care about the view corridors anymore, so you should allow our project to proceed.’ And in the face of that pressure, and I think they were, frankly, testing the fact that Larry and Ann were gone. And here's a 36-year-old city planner who's the director of planning now, and we can roll over him.

“And they were testing the resolve of City Hall in the context of the view corridors. This was not dispassionate. This was an active campaign to get rid of the view corridors.

“We stepped back and said, ‘I'm not going to give in to individual pressure on individual projects... We're going to do the review that had always been promised. We're going to look at it, and we're going to test the theory that the public doesn't care about view corridors, and we're going to see if that's true. And so out of that exercise came the answer: ‘Yes, the public does care.’”

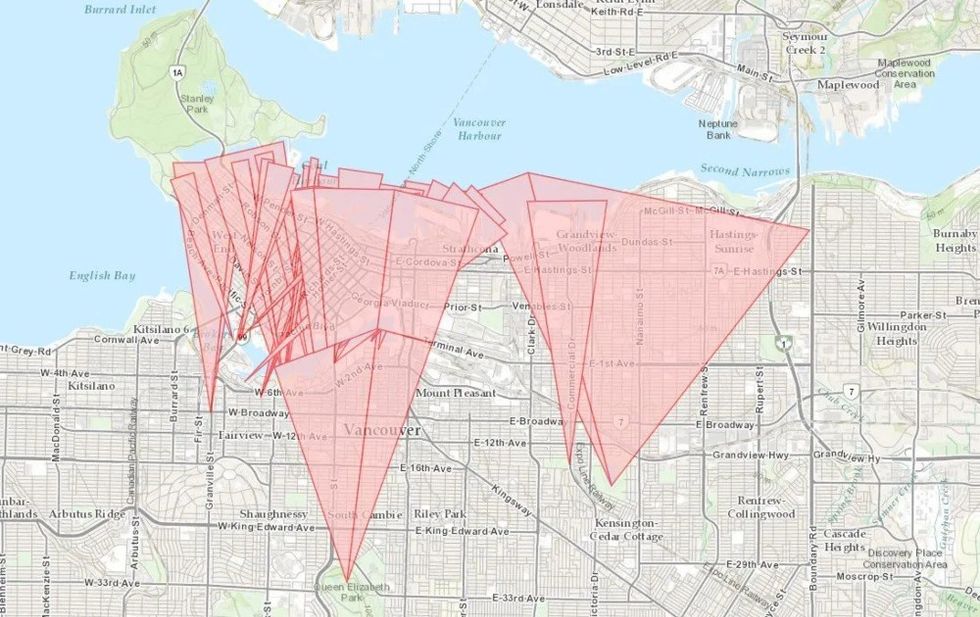

The city has 26 view cones, including a beloved one from South False Creek, with a view of the famous mountain shapes known as the Lions. A proposal to build a 56-storey tower nicknamed The Shard, developed by Intracorp Homes, would partially obstruct that view. As it turns out, the Intracorp application is also under review, which has raised some eyebrows as to why the ABC dominated City Council would choose this time to assess whether a few view cones should be eliminated.

An audience member asked Beasley and Busby if they were saying that the view cones are currently under threat.

“I think they're under threat,” said Beasley. “I look at the resolution as it was first put forward at Council. And it actually said in the resolution, the first part of it, it said, ‘review the view corridors with the intent to eliminate them.’ Now, fortunately, councillors had better thoughts and they edited out some of that. But I'm anxious that the bias is still there, and that if the staff's performance doesn't eliminate it, they'll be seen as failures and not doing their job.

“And that really worries me... I'm not sure this is a time for a review.

“The second thing is, I know there are one or two corridors where there's one or two proposals that are just hoping that those corridors get demolished so that they can do those proposals. And I know the dynamic at City Hall, between the development community and the political community, and the staff community, and I know the struggle that's there. And I'm not saying there's a bad person in this. I'm just saying there are different interests at play. And so I think we're better to say, ’let's confirm our corridors.’”

Toderian pointed out that this isn’t the first time that politics has played a role in the view cone debate. When it went to staff for a 2009 review, City Council then was also seeking to get rid of view cones. They only balked at the idea because of the optics, just before hosting the Olympics, he said.

“I think we are in another example where the public is going to have to decide, do you care about the view cones or not? And in the absence of a strong and compelling voice, I think the result will be different than it was in 2010.”

Beasley said a frequent rationale for eliminating the view cones is they get in the way of creating affordable housing. An audience member wondered if it was tone deaf to fret over views when homelessness is a major issue. Beasley said that affordable housing and protection of views are not mutually exclusive.

“I’m not sure it gives you the total cost benefit,” he said. “If, in fact, you bring architects and urban designers into the equation, they will show you how to achieve that density without necessarily having the tallest buildings on the planet.”

Another comment he hears a lot is, ‘does it really make too much of a deal if we just get rid of one view corridor?’

“And I say ‘yes,’ because every view corridor you lose is a nail in the coffin of all the view corridors. But even more important, if, as the director of planning, I said to one developer, ‘oh yeah, you can break the view corridor,’ how could I say ‘no’ to the next developer? You can't.”

There are cases where view cones do take a back seat to housing, such as the massive 11-tower project underway on reserve land in Kitsilano.

“First Nations property rights didn't exist in those days,” said Busby. “So Senakw, the development on both sides of the Burrard Street Bridge, would break a few cones. It will break view cones by the time it's built out. But their property rights are more important than those views registered some 34 years ago.”