Last week, after the City of Vancouver published the agendas for the council meetings to be held this week, it was revealed that Councillor Peter Meiszner would be introducing a motion that would initiate a review of Vancouver's view cones.

His motion, entitled "Modernizing the City’s View Protection Guidelines to Unlock New Housing and Economic Opportunities," was brought forth after Mayor Ken Sim alluded to conducting such a review in a speech at a Greater Vancouver Board of Trade event earlier this year.

Almost immediately after Meiszner's motion was made public, many Vancouverites voiced their concerns — and outrage, in some cases — about the possibility of removing protections of the city's famous views.

On Wednesday, in a Standing Committee on Policy and Strategic Priorities meeting, Meiszner's motion was approved, and City staff will now begin the review, setting off what could turn into another long and passionate debate.

For those who are a little uncertain of what's happening, here's what you neeed to know.

What are view cones?

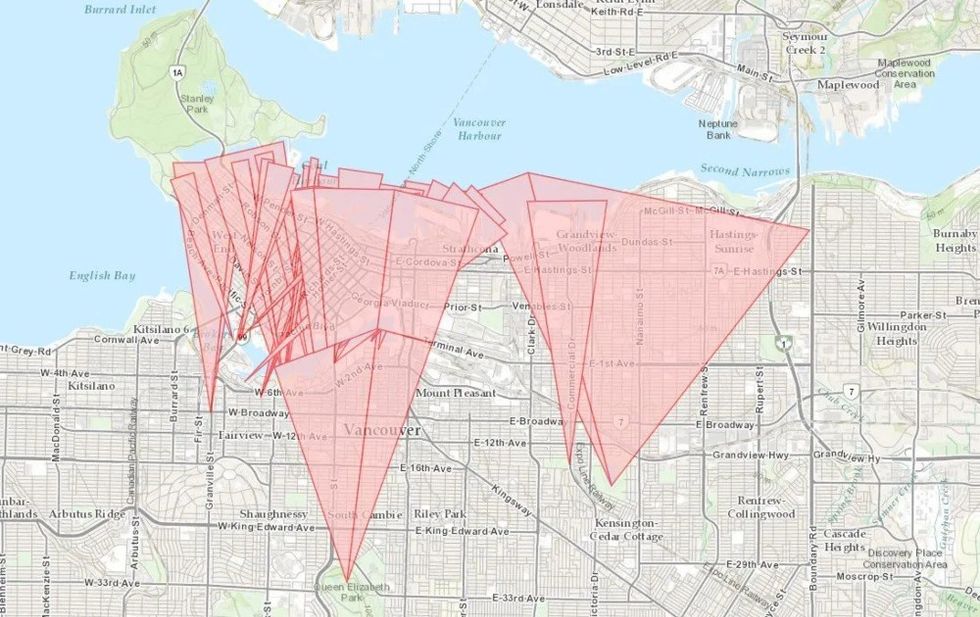

Vancouver's view cones.

(City of Vancouver)

View cones, sometimes referred to as "view corridors," are specific sightlines from specific locations in Vancouver that are protected by the City through policy. Most of these view cones provide clear views of the mountains, which would otherwise be obstructed by high-rise buildings if no protections were in place.

The protections were put in place in the late '80s and Vancouver currently has 26 protected view cones, including several from landmarks such as the Cambie Bridge, Granville Bridge, and Olympic Village, with views of the shoreline, the downtown skyline and the North Shore.

Why is the City of Vancouver considering removing view cone protections?

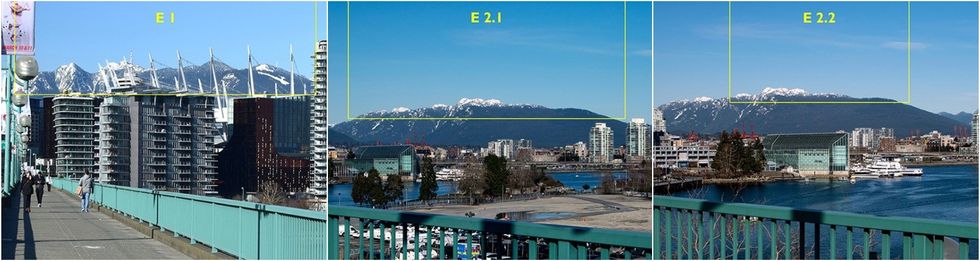

Three view cones from the Cambie Street Bridge.

(City of Vancouver)

The City is considering removing protections for some view cones because of Vancouver's housing crisis. Currently, these view cone protections limit density in certain areas, so as to not obstruct those views, and Council believes removing some of these protections would allow for more housing to be created.

As Councillor Meiszner has repeatedly said: "We aren’t in view cones or shadow crisis, but a housing crisis."

Why are people opposed to this? Is it NIMBYism?

In this particular case, it's not quite as simple as labeling those who are opposed to removing view cone protections as being NIMBYs — those opposed to any development in the area where they live.

The common argument among those in opposition, such as Melody Ma of Save Our Skyline YVR, is that what removing view cones actually does is privatize and monetize those views. Rather than being available to anybody at anytime for free, those view cones would become exclusive only to those living in the buildings that are erected.

What's the counter-counter-argument?

The Queen Elizabeth Park view cones.

(City of Vancouver)

Those who don't deny that eliminating view cone protections will privatize those views generally do not believe all view cone protections should be eliminated. They argue that some of the existing view cones are really not that important and that these should be the ones that should be potentially eliminated.

Others also point out that some of the view cones, such as the ones from the Cambie Street Bridge and Granville Bridge, are only visible for mere seconds when driving along the bridge, making them a reasonable trade-off for more housing.

In response, those in opposition say that this is a slippery slope, and that this could eventually result in more and more view cone protections being eliminated.

Is this something that's happening because developers are pushing for it?

It's unclear if Council is doing this because developers are pushing for it. Some developers have voiced support for the motion since it became public, and the current ABC Vancouver super-majority Council has voiced their intentions of making things easier for developers, but it's unclear if the development community was pushing for this behind the scenes.

Under the City of Vancouver's Transfer of Density Policy that was adopted in 1983 and amended several times since then, rezoning applications that request density transfers are possible for a variety of reasons, one of which is "to help implement Council-approved view protection policy in Downtown South."

Such density transfers allow the density that would be lost as a result of the view cone protections to be transferred to a different site, and they can even sell the density transfer, so developers are really not losing much either way.

Is this the first time the City has considered eliminating view cone protections?

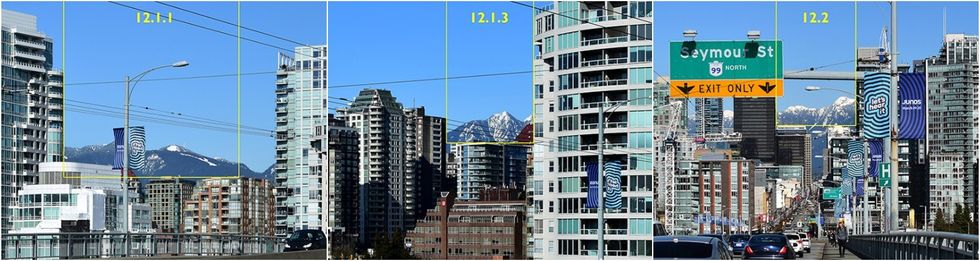

Some of the view cones from the Granville Bridge.(City of Vancouver)

Some of the view cones from the Granville Bridge.(City of Vancouver)Some people like to say history is cyclical and, as such, repeats itself. In the case of Vancouver's view cones, this is true.

In the recent past, view cone protections were centre to a development proposal made by PavCo — the provincial Crown corporation that owns and operates BC Place and the Vancouver Convention Centre — for a 40-storey tower on 777 Pacific Boulevard between BC Place and Rogers Arena that would encroach on the Cambie Street view cones.

The proposal set off a debate similar to what's unfolding now and the development proposal was ultimately approved in July 2018. However, to date, no tower has been built.

What happens now?

Councillor Meiszner's motion was approved unanimously on Wednesday, with some minor amendments to the wording.

The original motion pointed to view cones that could be "eliminated" — using the word several times — but has since been amended to soften the language and now uses words such as "refining," "adjusted," and "considering for removal."

City staff will now begin the review and are expected to report back to Council before the end of the year with their findings and recommendations.