This piece was written and submitted by Carolyn King, President & Board Chair of the Shared Path Consultation Initiative, and Richard Joy, Executive Director of ULI Toronto.

The places we design, build, and live within are more than bricks and mortar — they are expressions of our values. For too long in Canada, our communities and their built environment have been shaped without fully recognizing and meaningfully engaging the rights, histories, and voices of Indigenous Peoples. That must change.

Over the past several years, Shared Path and ULI Toronto have walked alongside more than 30 leading real estate and development organizations to explore what meaningful Truth and Reconciliation can look like in our industry. This was not a quick project or a box to tick. It has been a sustained dialogue and relationship— informed by cultural, treaty, legal, and historical education, guided by Indigenous leadership, and built on trust that took years to earn, as truths were shared.

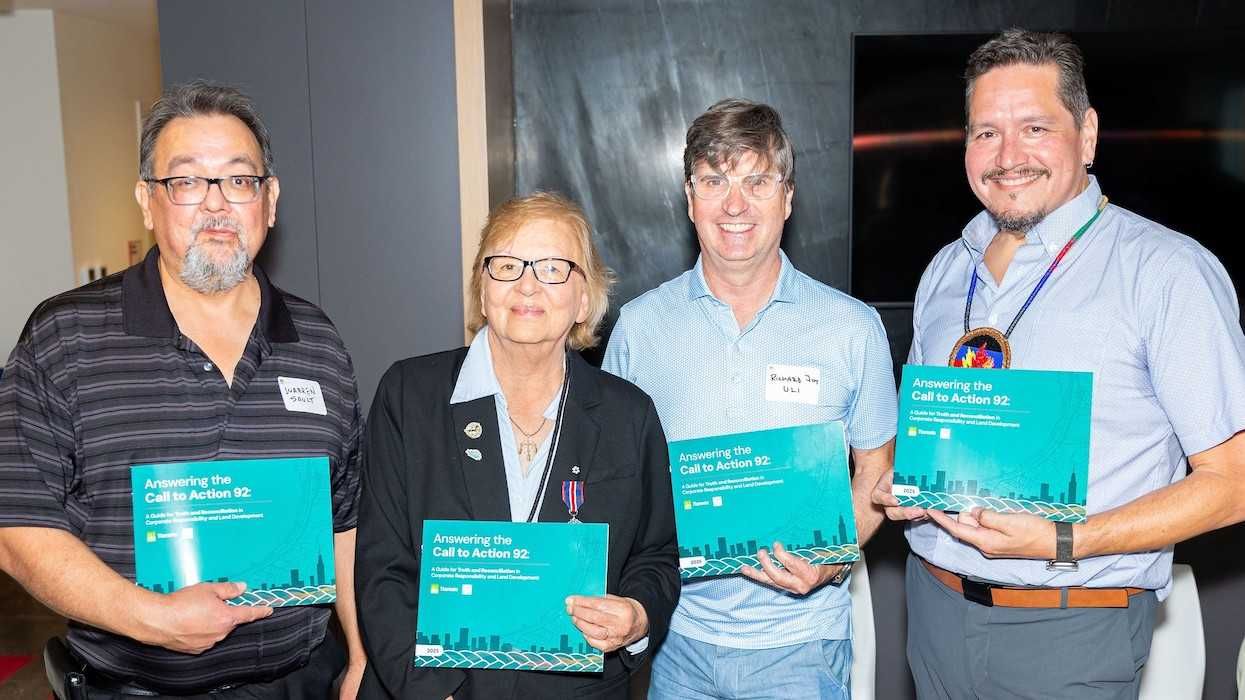

The result is Answering the Call to Action 92: A Guide for Truth and Reconciliation in Corporate Responsibility and Land Development. It’s the first comprehensive framework of its kind for Canada’s real estate sector, launched in ceremony this past June at Northcrest Development’s YZD Experience Centre. It is a landmark resource, grounded in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action 92 and informed by the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

This guide is practical by design. It offers concrete actions across four interconnected pillars: governance and co-development; education; equity and economic opportunity; and relationship building. These are not abstract ideals — they are operational steps, such as creating Indigenous advisory roles at the board level, co-developing reconciliation strategies with First Nations, Métis and Inuit, embedding cultural competency training into corporate culture, and ensuring equitable access to jobs, contracts, and long-term benefits for Indigenous Peoples.

Perhaps most importantly, the guide challenges organizations to go beyond compliance. It calls on real estate developers and leaders to integrate First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives into land use practices and corporate strategy. The purpose: to honour free, prior, and informed consent before advancing economic development, and to see reconciliation not as a one-time initiative but as a sustained relationship embedded in how we plan, build, and invest.

The impetus is clear: The real estate and land development industry has a unique influence over land — and therefore a unique responsibility to steward it in ways that reflect the values of gratitude for life, respect, reciprocity, and shared benefit. Real estate decisions shape the use of traditional territories, influence natural and cultural landscapes, and determine who benefits from economic growth. Done without care, cultural connections to the environment can be severed and harm perpetuated. Done with intention, land development can help restore relationships, protect land and water, and create prosperity that is shared.

There are compelling reasons for the private sector to act. True reconciliation strengthens relationships, mitigates legal and reputational risk, attracts investment, and enriches the cultural and social fabric of our communities. Forward-looking companies are already discovering that identifying and working with a local First Nation’s values in development can lead to innovative partnerships, faster approvals, and projects that enjoy greater public trust and local support.

This work matters not just because it is right, but because it is necessary for a sustainable future. The guide’s case study on the Memorandum of Understanding between the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation and Northcrest Developments shows that building trust, creating economic opportunity, and weaving Indigenous culture into design can be transformative — for both the community and the business.

We know this is a journey that requires humility and persistence. It starts with listening — with making space for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit voices to shape how decisions are made. It requires education, not only about history and rights, but about the living cultures, governance systems, and aspirations of the Indigenous Peoples whose lands we work on. And it demands accountability: setting goals, measuring progress, and being transparent about both successes and setbacks.

We invite every real estate and development leader to see this guide as both a challenge and an invitation. A challenge to examine the values that shape your practices with honesty, and an invitation to begin — or deepen — your own reconciliation journey. The guide is not a checklist to complete — it is a framework for continuous learning, relationship-building, and shared action.

As we approach the fifth National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30, we are reminded that reconciliation is not a destination, it is a relationship — one we must nurture together. The communities we build today should stand as places of respect, inclusion, and shared prosperity for generations to come. The land remembers how it has been treated. Let’s ensure that what we build upon it tells a story we can be proud of.

For more information you can visit ULI Toronto’s Truth and Reconciliation pages.