Last week, Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow appointed new chairs to her various council committees, and in a city embattled by a worsening housing crisis, there is perhaps no chair position with more eyes on it than that of the Planning and Housing Committee.

The committee has inherited the daunting task of tackling the city's housing shortage and unaffordability — a task few Torontonians would likely want to take on. But Chow's pick for Planning and Housing Chair, Councillor Gord Perks (Parkdale-High Park), a veteran councillor with 17 years of experience, says he's excited for the opportunity.

"I've been on the Planning and Housing Committee for most of my time on Council, and we've done a lot of very innovative housing work, and work for the ward I represent, and I'm just thrilled that Mayor Chow, who has a really comprehensive and ambitious housing program, has tapped me on the shoulder and asked me to help her deliver it," Perks told STOREYS.

In his time on the Planning and Housing Committee, Perks has championed many of the City's progressive housing decisions, including the legalization of rooming houses city-wide — a years-long effort under former mayor John Tory. Perks is a staunch affordable housing advocate who has worked to preserve affordable units in his ward, and has supported implementing robust inclusionary zoning policy.

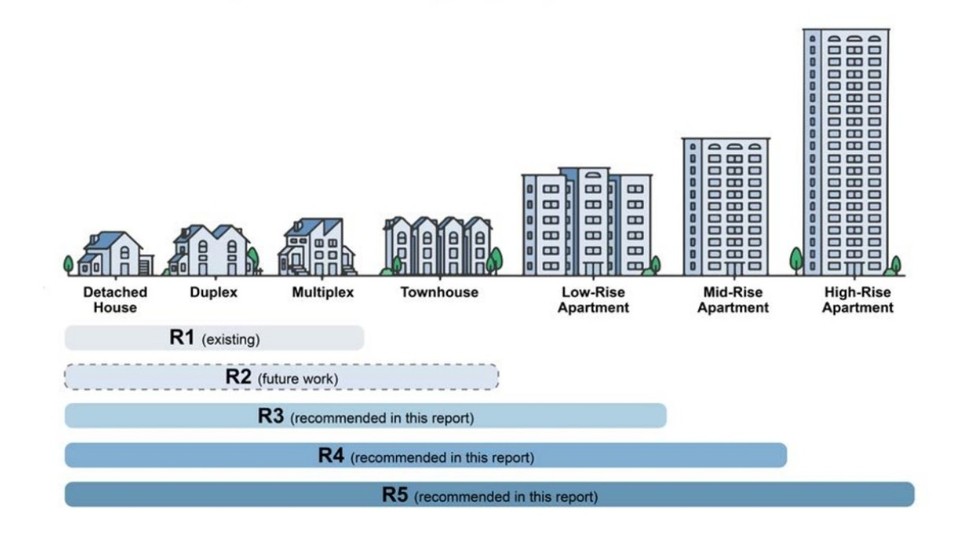

Despite these recent advances in the City's housing policy — like the move to legalize four-unit multiplexes on all single-family lots — owning a home in Toronto is indisputably becoming an increasingly far-off dream for many — something Perks hopes to make progress on.

"There's just a big systemic hurdle, which is that unless you're very high income, or you come from a family with some wealth, Toronto's becoming a less and less viable housing market, and we need to attack that vigorously from a lot of different directions," Perks said.

An Intergovernmental Approach

Perks underscores a need for all three levels of government to come together on the housing issue, noting that part of the problem stems from the provincial and federal governments backing off of public investment into mixed-income and low-income housing in the late 1990s.

From the Province, specifically, Perks says there needs to be an end to the "erratic fits and starts."

"It seems that every six months, we have a completely new planning regime," Perks said. "We need a coherent planning regime that is predictable and reliable, both for municipalities and also for the building and development district."

The Province has made clear on more than one occasion its disdain for providing additional funding to the City of Toronto, but he points to Mayor Chow as a beacon of hope, noting she is "one of the most skilled elected officials in the country at getting different people together to get good outcomes quickly."

"Nobody thought that there was an easy answer to the lack of housing for refugees, and literally in her first week in office, Mayor Chow got commitments from two other orders of governments and a number of civil society organizations and brought some of the City's own resources to the table and made progress no one believed was possible despite eight years of the previous administration doing everything — well, doing what it said it could do. So that incredible skill she has of breaking logjams I think can be applied to other kinds of housing programs as well."

The Ontario government has, in some regards, recently tied Toronto's hands when it comes to delivering affordable housing. Bill 23, the More Homes Built Faster Act, set a 5% maximum for the number of affordable units that can be required by municipalities' inclusionary zoning policies. This came as a hit to Toronto, which just one year prior set out new inclusionary zoning guidelines that would require up to 22% affordable housing by 2030.

Inclusionary zoning requirements are often rebuked by those in the development industry, so the Ford government delivered them a win. But Perks says he hopes that the recent (and scathing) Auditor General's report regarding the government removing lands from the Greenbelt in a manner that showed preferential treatment towards certain developers — developers who will see their land values increase by over $8B — will have taught the Province a lesson.

"Which is eliminating all the rules and doing back backroom deals doesn't make affordable housing, it just makes a billion dollars in windfall profit," Perks said.

Reshaping Toronto's Housing Lens

Although changes like legalizing garden suites and laneway houses and upzoning neighbourhoods will undoubtedly add more housing stock to the city and were changes "worth doing," Perks says they won't be meaningful in terms of affordability.

"It's not going to be very fast, and they're not going to be terribly affordable," Perks said, adding that "These solutions will only ever house people who are paying the kind of rents that return huge profits, or the kind of mortgage that returns huge profits."

"We need to provide more options, absolutely, but if you want to solve the problem, you need to really do things like inclusionary zoning and public investment."

During her first transition meeting, Chow emphasized the need for community-focused models for building new housing, pointing to Scarborough's Golden Mile master plan as a shining example of the beneficial development that can come about through public-private partnerships.

Perks says there are hundreds of different ways for community-led development to be made the centrepiece of the City's housing plan. One such way that seems promising, and builds on Chow's vision, is through more socialized housing. He points to European cities like Vienna, Helsinki, and Stockholm, where affordable, city-owned rentals are abundant and well-received, as models of what Toronto could aspire to.

"You start touring through some of the success stories in Europe, like Vienna where the majority of people live in some form of social housing, or Helsinki where they have no homelessness, and you realize there are many models we can be importing here," Perks said.

In his years as a City Councillor, Perks has already started to bring these kinds of ideas to Toronto. In 2018, he pushed for a pilot program in his ward of Parkdale-High Park that saw the City work with a local land trust to purchase rooming houses that were at risk of being sold to private developers. The program has now gone city-wide as the Multi-Unit Residential Acquisition (MURA) program.

"It actually costs less than half as much to preserve a unit of affordable housing than to build a new one, and part of why we're in the mess we're in is that we have been losing affordable housing faster than we can build it," Perks said.

He also points to the success of modular housing in his ward — one of the first in the city to start a program for the quick-to-build housing type — which can be an effective way to get people housing sooner.

"We're getting close to completing a project we did in partnership with the University Health Network, where they pointed out that the cost of treating homeless people in emergency rooms was greater than the cost of housing," Perks said. "So they've partnered with the City and the United Way and we're building some housing for people who were relying on our hospital system to stay healthy and housed."

The choices for creating affordable housing in Toronto are abundant, he says, but they rely on City Council's willingness to embrace them.

"There are more ways to succeed here than there are to fail," Perks said. "We just need to be more creative and more activist than previous municipal councils have been."

- Rooming Houses Framework Delayed Again, This Time Until Early Next Year ›

- King Street condo plan reveals NIMBYists' fear of heights ›

- Toronto Green-Lights 6 Storeys On Major Streets, Extends RGI Deadline ›