Last week’s interest rate hike from the Bank of Canada sent a jolt of alarm through many Canadians. After halting its aggressive hiking cycle in March and April, the BoC started hiking again in June, and on July 12, it pushed its key lending rate to 5%, the highest level since 2001.

This has had an immediate effect on mortgage rates. The discount rate for a five-year fixed-rate mortgage pushed past 5% in recent weeks, the first time that rate has been this high since 2009. Nearly an entire generation of homebuyers has never seen mortgage rates at these levels. And with the federal mortgage stress test in place, borrowers now have to qualify for a mortgage at a rate above 7%.

This is causing concern – among real estate professionals worried about a possible downturn, among indebted homeowners facing rising mortgage rates at renewal, among media commentators who argue the BoC’s policy amounts to a war on workers, and among economists who say that, since inflation has been declining for half a year, the BoC’s job is done and it shouldn’t be hiking rates any longer.

This broadly emerging consensus that the BoC has gone too far was reflected in a recent CBC article headlined "Is the Bank of Canada making things worse?"

Yet that article doesn’t quite answer the question: Worse than what? Many people at this point seem to believe that what Canada is facing is a simple choice between higher interest rates that squeeze mortgage-paying homeowners, potentially setting up household bankruptcies and a housing market crash, and lower interest rates, where households aren’t squeezed, and the economy runs smoothly. If only it were that simple.

Sadly, the real choice we face today – the choice facing the BoC’s policymakers – is between a tougher lending environment under high interest rates, or out-of-control inflation under low interest rates.

Inflation Isn’t Done With Us Just Yet

But wait, you say. Inflation came in at 2.8% in the latest reading. So, hasn’t the problem been beaten?

Not really. In fact, much of the decline in inflation in recent months is a statistical illusion. A large part of the recent drop in the consumer price index is due to lower gas prices this year than at the same time last year. Strip away the effect of gas prices, and Canada’s inflation rate would be about 4% – not as bad as the 8% seen at the peak last year, but still double the BoC’s target (i.e. its idea of a healthy inflation rate).

There is also a “base effect” at play here. Consumer prices are measured in comparison to a year earlier. Last spring saw very high gas prices, which began to come down in the second half of the year. So, this spring’s gas price levels compared against the very high gas prices of a year ago make the inflation rate look low.

But, as the year wears on, we’ll be comparing gas prices to the lower levels seen later on last year. Even if inflation didn’t accelerate at all and stayed steady at its current pace for the rest of the year, by December of 2023 our inflation rate would be hovering around 4.5% – simply from the base effect.

The BoC knows this – so it knows that to avoid inflation “rising” by year’s end, prices need to continue decelerating.

The BoC also knows something about the history of inflation; namely, that inflation is rarely ever a one-and-done phenomenon. That is to say, inflation tends to come in repeated waves.

For instance, during Canada’s inflation bout in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the country saw two distinct inflation waves. Inflation soared to above 15%, then fell almost all the way to zero, before spiking back up to nearly 15% again within a few years. The same pattern played out during the inflation bout of the 1970s and '80s, though with less exaggerated movements.

So, it’s entirely reasonable that the BoC doesn’t believe we are out of the woods yet. The central bank is on the lookout for any signs that inflation may stage one of its traditional comebacks – and in the past six months, the economic situation in Canada has given the bank plenty of reason to think that inflation isn’t finished with us yet.

The ‘Inflationary Mood’ Continues

How does the Bank of Canada determine which way inflation will be going next? Looking at raw economic numbers can only go so far, because this data is backward-looking – inflation, wage and retail spending numbers tell you what happened last month or the month before, not what will happen next month or the month after. For that, you have to look at leading indicators, such as business and consumer sentiment, as well as spending intentions.

Sentiment in Canada has held up very strongly. Talk of a recession caused by rising interest rates has receded. Consumer spending has remained strong. And perhaps most significantly, the housing market roared back to life the moment that the BoC took its foot off the interest rate pedal.

Between January and June of this year, the average selling price of a residence in Toronto jumped by more than $140K, to $1.18M. That’s a nearly 14% increase in half a year, or a 28% annual rate. And that’s not due to interest rates coming down – it was due just to interest rates not rising anymore.

If house prices can spike 30% in a year simply on the expectation that mortgage rates won’t rise anymore, that’s a clear sign that the “inflationary mood” in the economy isn’t over.

And if new car prices can soar 30% compared to before the pandemic, and that doesn’t stop car sales from jumping 11.3% so far this year, that, too, is a sign that the “inflationary mood” isn’t over. Why would your local store stop raising prices if you’re still buying all the same products at these higher price levels?

This is what BoC Governor Tiff Macklem is talking about when he discusses “excess demand” in the economy – all the price hikes over the past two years, and all the interest rate hikes over the past 18 months, haven’t changed consumer or business behaviour – or at least not nearly enough.

The BoC Wants To Scare You

Central banks are in the business of adjusting behaviour. The only successful mechanism anyone has ever devised for reducing inflation is to reduce demand.

(You can try mandating price controls, but those have failed spectacularly throughout history, leading to the creation of black markets where – because of the risk of operating illegally – prices are even higher than they were before the price controls.)

“Reducing demand” is a technical term for something ugly: It means convincing consumers to spend less, and the best way to do that is to scare them – scare them into worrying about losing their job, or facing higher bills or reduced savings in the future. A scared consumer holds back on purchases and saves for a rainy day.

So, this is the point of the BoC’s recent hikes. A 0.25-percentage-point hike in interest rates won’t make much difference in terms of the raw numbers in our economy, but if it convinces businesses and consumers that worse times are ahead, now that will make a difference.

What the BoC actually wants is for you, the consumer, to throw in the towel. When you give up your expectations of lower interest rates, and adjust your behaviour accordingly, and when retailers and wholesalers and lenders do the same (i.e. the inflationary mood dies), that’s when the BoC might finally be comfortable putting an end to the interest rate-hiking cycle.

And so therein lies the paradox: As long as you expect the BoC to drop rates, and as long as most other people do too, the bank can’t do it, because of the risk of a return to inflation. Only when you and other consumers give up on that idea can it actually become reality.

Yet the question remains: Does inflation really matter that much? Isn’t a housing market crash, which could cause a recession, a worse scenario than a couple more years of elevated price hikes?

The problem is that these two scenarios aren’t mutually exclusive. In fact, a second wave of inflation could actually cause a housing market bust.

The Devastating Impact Of A Second Inflation Wave

For a good part of the past 18 months, it was possible to land a mortgage in Canada with an interest rate significantly below the inflation rate. For instance, in June of 2022, when the inflation reading was at 8.1%, the average discount rate on a five-year fixed-rate mortgage was 3.6%.

There’s really only one reason why a lender would hand out a five-year loan for 2.5 percentage points below the inflation rate, and that is the lender’s belief that this bout of inflation is temporary and will come down quickly. In essence, the desire to remain competitive in the mortgage lending business overshadowed any fears about losing money to inflation.

That belief has held up so far – but it might not if inflation makes a comeback. A second wave of inflation could convince many lenders that inflation is here for the long term, and if that happens, the fear of losing money to inflation would overshadow the desire to stay competitive in the lending space. If inflation makes a comeback, we can expect an immediate spike in borrowing costs.

Though the media narrative focuses on the influence of the Bank of Canada on interest rates, the reality is that bond markets (i.e. lending markets) also respond to other economic conditions, especially inflation.

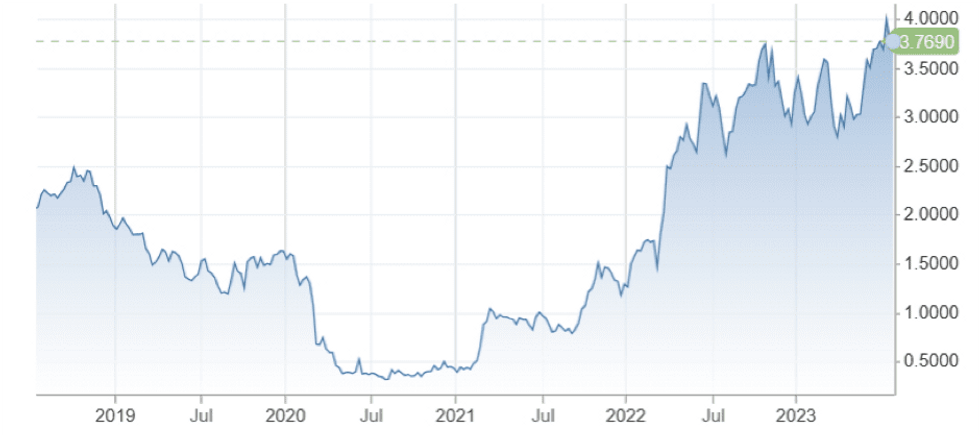

Note, for example, that the interest on a five-year Government of Canada bond (which is linked to the interest rate on five-year fixed-rate mortgages) began rising in the first half of 2021, at exactly the same time that inflation began rising, and nearly a full year before the Bank of Canada started hiking its own key lending rate.

A second bout of inflation would see the same thing happen, but on steroids. This time, lenders would be far less willing to lend money at rates below inflation. It’s easy enough to imagine mortgage rates pushing up to 7%, if and when inflation hits 6% again.

This would result in the exact same scenario as if the Bank of Canada had kept pushing its key lending rate higher – unaffordable mortgages, people being forced to sell, a correction in the housing market. Except in this scenario, there would also be high inflation.

Simply put, ignoring inflation would not result in a return to low mortgage rates. In fact, the very belief that policymakers are ignoring inflation could send mortgage rates to astronomical heights, as lenders seek to cover any losses from possible future bouts of inflation.

Thus, the BoC wants lenders to keep believing that inflation will recede, and the only way to do that is to show lenders that the bank is seriously fighting inflation. Better to hike the key lending rate and have 5% mortgages today than lose the fight with inflation and have 7% mortgages six months from now.

And today, inflation could prove to be much more harmful to households than it has been in the past.

During the long stretch of high inflation in the 1970s and into the 1980s, wage earners were largely protected from price hikes through cost-of-living adjustments that made up for their loss of purchasing power. That’s largely because, back then, a high proportion of workers were unionized, and unions had the pull to demand wage increases. And in order to stay competitive in the labour market, employers of non-union workers had to raise wages as well.

Today, unionization is much less common outside the public sector, and unions don’t have the same influence on wages. And over the past two years of inflation, we have seen the effect of that. In the two years from April 2021 to April 2023, consumer prices jumped by 11.35%, according to StatsCan data. But average weekly earnings for all workers rose by just 6.3% in that time. In real terms, Canadians have lost 5% of their purchasing power in two years.

Imagine this situation going on for a decade. After 10 years, Canadians would in effect be 25% poorer. With so many households paying gigantic mortgages, a 25% decrease in earning power would crush consumer spending, and the economy with it.

This is why central banks fear inflation. They understand that not fighting it will result in all the bad things that come with fighting it, but on top of that, you also have the destruction of earnings that comes with unbridled inflation.

As hard as it is for many people to accept, the BoC’s aggressive fight against inflation is the less painful path forward. The cause of this inflation – rampant money printing during the pandemic – can’t simply be undone. The money’s been printed and spent into the economy.

In which case, the best path forward is to fight inflation. Better to have squeezed consumers and hobbled the housing market than to have squeezed consumers, hobbled the housing market, and shrunk earnings due to runaway inflation.

Sadly, those are our options. We’re just going to have to ride this one out.