From project delays to cancellationsto receiverships (did we mention receiverships?), higher interest rates have given rise to no shortage of troubling real estate trends. And although the worst of rate hikes may be behind us, one economist warns that there’s more fallout on the horizon.

Stephen Brown, Deputy Chief North America Economist for Capital Economics, writes in a recent note that the country could be in store for an uptick in forced home sales as Canadians struggle to refinance their mortgages with traditional lenders.

“Most mortgages are provided by chartered banks, which must ensure that borrowers meet the mortgage stress tests set out by the financial regulator OSFI,” says Brown.

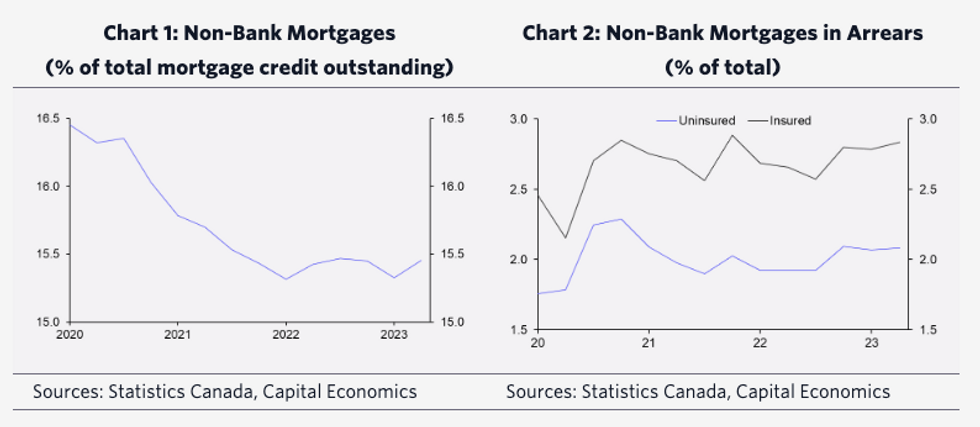

But it seems the tides are changing. Brown says that borrowers are increasingly turning to non-bank lenders (think: a credit union or mortgage investment entity), pointing to Statistics Canada’s data on non-bank mortgage lending, which dates back to 2020.

“On the face of it, the recent release for the second quarter does not show much cause for alarm. The share of non-bank mortgages was no higher than in late 2021 before the Bank of Canada began raising interest rates, and the share of non-bank mortgages in arrears was well within the range seen in recent years.”

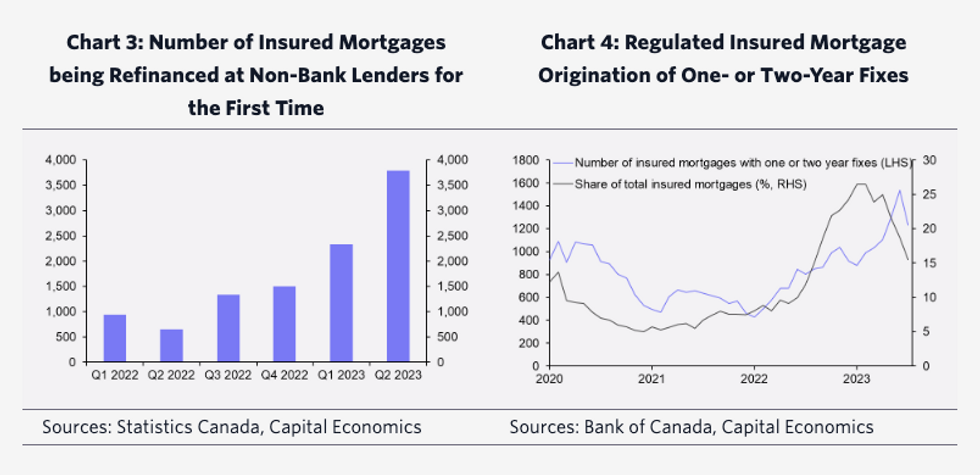

However, Brown notes that limited data available for 2022 shows a jump in the number of insured mortgages — those with a loan-to-value ratio of more than 80% — being refinanced with non-bank lenders for the first time.

More specifically, there were 3,784 insured mortgages refinanced with alternative lenders for the first time in the second quarter, and that figure represents 4.3% of refinancings at non-bank lenders and close to half a percent of total refinancings.

“The rise in insured mortgage refinancing with alternative lenders suggests many borrowers are no longer able to pass the stress tests at their original provider,” Brown explains.

He adds that the rise is particularly concerning as most borrowers refinancing around now should be in a “relatively healthy” position.

“Most started their mortgage terms five years ago, when five-year fixed mortgage rates were 3.5%. They have benefitted from five years of cumulative house price gains, totalling 40%, and face a smaller rate increase than those that took out a mortgage during the pandemic,” he says.

Brown also warns that the coming months will see an increase in the number of insured mortgage holders struggling to refinance.

“While non-bank lenders stepped in to help these borrowers earlier this year, they may be less inclined to do so now that falling house prices are further eroding borrowers’ equity and the economy has entered recession,” he says.

“The upshot is that the risk of forced home sales is rising. The tentative signs of a stabilization in new listings in the October local real estate board data provide some comfort, but there are clear downside risks to our forecast that house prices will fall by only 5% over the next six months.”