As Toronto maintains its title of ‘Crane Capital of North America,’ its skyline and city streets continue to change with each new towering condo development. In a city of largely unattainable home prices and a climate of sky-high interest rates, the reality is that many condos of tomorrow will house families with children.

At least, that’s the message that has been driven home repeatedly, as city planners and politicians urge developers to create more residential developments for families.

Increasingly, design plans submitted to the City for Toronto’s new builds indeed reflect an agenda to cater to families, with plans for family-centric amenities like kids’ party rooms, playrooms, and playgrounds. While the micro condo had a moment to shine – and still is undoubtedly needed, especially in this dramatic rental market, where a studio unit costs $2,000 each month – developers are now showcasing floorplans for larger units that could comfortably house families.

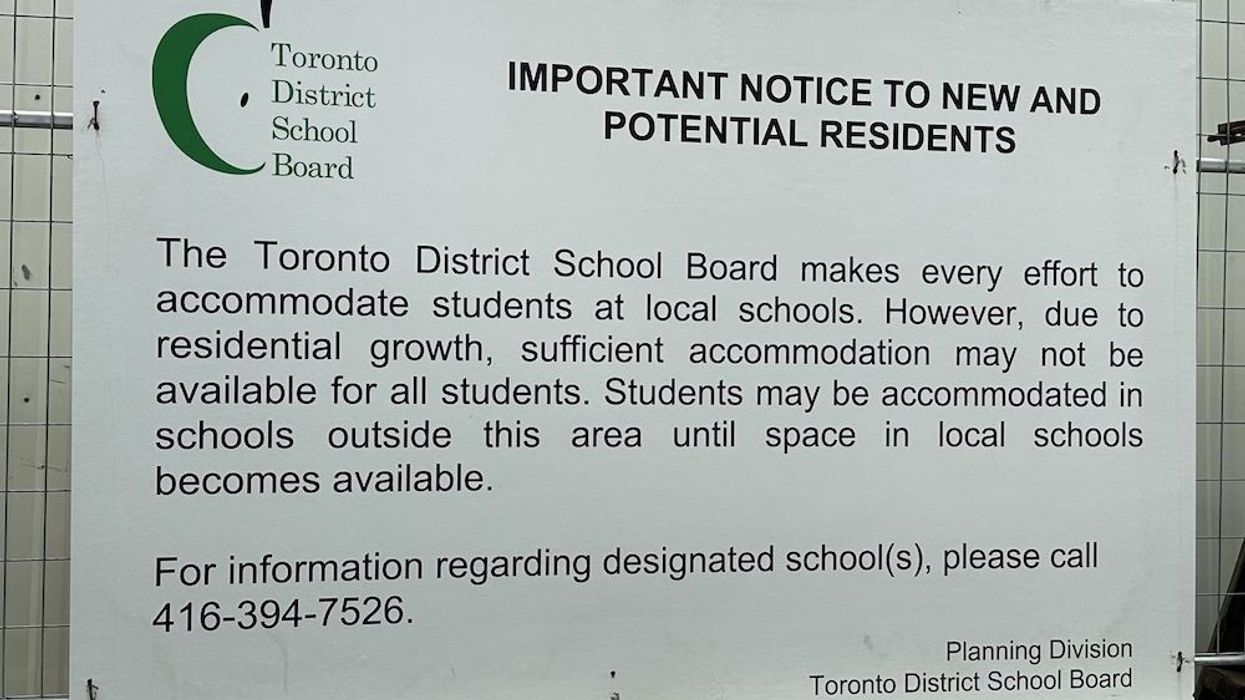

But, as you may have noticed, many of these sites of future condos have one common feature – and it has nothing to do with their design. Rather, they present the same sign in front of their site from the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), informing any future residents (before they even make an offer) that the nearby schools are full and that future child residents may therefore be redirected to schools further away.

“It is part of the City’s agenda to encourage families to move into higher density accommodation, but at the same time, they’re telling them their child may not have the ability to attend a school a block away,” says Jon Love, Founder and CEO of KingSett Capital, who inspired a passionate LinkedIn thread on the topic last week.

As we kick off the school year today, how big of a problem is Toronto’s school space relative to its growing population? Well, it may depend on who you ask.

Overcrowding is Not a New Problem in Toronto Schools

While they are undoubtedly more prevalent now, the TDSB signs aren’t actually new. In fact, they started popping up in Toronto as early as 2012. Furthermore, some schools in certain neighbourhoods – like North Toronto – have been at capacity for notably longer than that.

According to a 2012 CBC article, one such sign from the TDSB appeared in front of an upcoming development at Lansdowne Avenue and Davenport Road. That same year, parents took to the media to say that their children's schools were alarmingly overcrowded. Concerned parents claimed that Keele Public School and Swansea Public School were 30% over capacity and even lacked adequate access to proper gym space and washrooms. Furthermore, the rapidly gentrifying Leslieville neighbourhood made headlines in 2017, when concerned parents complained the condo boom had local schools overflowing with kids. The coveted east end neighbourhood continues to be hard-hit on the school capacity front.

It’s no secret that portables – usually a sight reserved for suburbia back in the day – have very much found their way onto TDSB property in recent decades, becoming staples at many schools across the city.

At the time of publishing, the TDSB had not returned STOREYS’ request for comments. On the TDSB's “City Growth and Intensification Strategy” webpage, however, the school board acknowledges that it operates in a rapidly growing city and therefore needs an adaptable strategy to accommodate this. “We closely monitor Toronto’s population growth and plans for new residential developments throughout the city,” reads the website. “We try to accommodate students at local schools. When there is no room, we look at many different strategies.”

It proceeds to outline a handful of alternative strategies, which include everything from closing schools to out-of-area students, reconfiguring/retrofitting existing spaces, and adding portables, to switching up timetables (for post-secondary students), changing school boundaries, and opening up previously closed schools. Of course, it also suggests redirecting students from new residential developments.

“A redirection is considered when a new residential development is proposed to be constructed in an area that is served by an overcrowded school,” reads the website. “This means that students from new residential developments may be sent to other schools outside of the immediate area until space becomes available at local schools.” According to the TDSB, these residential redirections are a temporary solution used to manage growth. “The goal is to return students to their local schools in the future when space becomes available,” it says.

Naturally, capacity issues hit some neighbourhoods harder than others. “With every development that goes up, there’s a sign put up by the school board that tells parents not to expect to have space in the local school — that’s the norm,” says Toronto City Councillor Mike Colle of his rapidly developing ward (Eglinton-Lawrence) — part of which includes the upcoming (at some point, at least) Eglinton Crosstown LRT and all the new development that comes with it.

Colle says that all the schools in his ward – which is undoubtedly filled with coveted neighbourhoods for young families – are filled to the brim. “Right now, they don’t have room for new students, and I don’t know how new residents are going to go to local schools,” he says. “Now, residents’ kids are going to have to go to school outside of a neighbourhood their parents bought in – they either have to take the bus or get their parents to drive them. It’s rare for a family to move into a new condo or purpose-built rental in the ward and have their kid attend the local school.”

Colle does acknowledge, however, that his ward happens to house some of the best schools in the country – “the top 20 schools in Canada,” he says – something that’s always been a huge draw for young homebuyers. “Most of them have been at capacity for 20 years,” says Colle of the schools.

This isn’t the case everywhere throughout the city. In fact, some schools are actually dropping their numbers, with many underutilized TDSB schools throughout the city – especially when it comes to high schools. A new law introduced by the Tories in August gives the Ford government the power to turn Ontario’s underutilized schools into affordable housing or to sell them off on the free market (to developers, most likely).

There are fees that the TDSB can leverage from developers to expand capacity at local schools in the area, but, due to this imbalance in registration, they don’t qualify to do so.

“The TDSB said a few years back that there is a lot of surplus land of practically empty schools, so what we have is a distribution issue,” says Toronto-based urban planner Naama Blonder. “So, the distribution of Toronto schools isn’t in line with our density distribution. But density is sort of easy to predict because the city directs growth to very specific areas. So, it’s an interesting misalignment we’re seeing.”

Blonder is a passionate advocate of strategic density and raising kids in condos in the city core. She lives in a downtown condo with her young family herself and says this represents the future of urban living for countless Canadian families.

Are Families Really Buying Condos?

While an influx of kids in condos may be the reality in the coming years – and there are undoubtedly more strollers coming through downtown condo lobbies as of late, nobody can dispute that – some Toronto realtors say that overcrowded schools relative condo developments isn’t a huge problem they’re encountering in the market. While Toronto schools – especially those in the city’s most desirable neighbourhoods – may be busting at the seams, they say this isn’t a huge issue for their clients.

“We’re currently not getting this feedback,” says Toronto realtor Natalie Sutton Balaban. “Condominiums that families want to live in – when you factor in the neighbourhood, the unit layout, and size, are not widely available. When these units become available, they come with a high price tag that’s at times greater than or equal to a single-family home with the same square footage. Planning initiatives have prioritized larger units to come down the pipeline. As more of those come to fruition, we will likely hear more of that feedback.”

Toronto-based realtor Davelle Morrison shares a similar sentiment. “There are many condos built around the city with these signs,” says Morrison. “The schools in better neighbourhoods are at capacity and they’re basically saying, ‘You can live in this building, but you can’t go to this school.’ So, that’s a thing. But, I will go back to the whole notion of the ‘condos for families’ narrative. I’ve heard people like city councillors ask why they don’t build more of these, and there’s a reason.”

There isn’t currently a disconnect between the number of “family-sized” pre-construction units sold and the families-in-condos narrative, says Morrison – and it comes down to money and getting shovels in the ground faster.

“A developer puts out a plan with all their different units listed when they put up their sales centre,” says Morrison. “What ends up happening is that investors say they want a one or two-bedroom unit. The end user of the three-bedroom unit is not someone looking to buy at the pre-construction sales office phase. They’ll buy after it’s built. But for the developer, they need 75% of the units sold. So, if you need to sell this much, you’re going to build what people have bought on spec. If people aren’t buying three-bedroom condos on spec, they aren’t going to build them because they won’t be able to get their financing to get the building built.”

So, the developers hold back these buildings, because they know nobody will buy them, says Morrison. “After the building has been registered, that’s when they finish the three-bedroom condos and put them on MLS,” says Morrison. “Those condos – and I’ve been showing them – are over $2-3M. Those buyers don’t want to buy off plan, they want to see what they’re getting.”

Rather than young families, Morrison says that most of the people who are buying these three-bedroom condos are older, wealthier downsizers.

“If you’re looking at a three-bedroom condo these days, it’s most likely going to be over $1M,” says Morrison. “And if you’re going to look at a condo for over $1M, you may as well look into buying a house. It makes sense for a young family to buy a home elsewhere where their kids are guaranteed to get into the local school.”

It should be noted that children in single-family homes are guaranteed access to the public school. “It’s actually pretty elitist if you think about it,” says Morrison.

Colle doesn’t shy away from addressing the affordability issue in his ward, where single-family homes can sell for $3M to $4M and beyond. “I’m up to 115 new condo and purpose-built rental buildings in my ward,” says Colle. “That’s about 25,000 units, but very few of them are affordable because the Province wouldn’t let us have affordable inclusionary housing in the new developments. We have a downward spiral in terms of affordability for everyone – developers, builders, buyers, and renters. The affordability is also out of reach. Who can afford to buy or rent large enough condos for the average price?”

Of course, persistently high interest rates don’t help.

As a result, more families are turning their sights and their dollars to more affordable pastures outside of the city boundaries, to places like Oshawa, says Colle. Of course, that only puts more pressure on the schools in the rapidly growing suburbia. So, it’s time we think of a sustainable solution for our students and the future of schools.

The Schools of Tomorrow

The reality is that we need to rethink the way we design schools as Toronto increases in density with each record-breaking immigration target and new residential development. “There was a time when a Toronto school was four acres of land and a two-storey building; well, we’re out of those,” says Love. “So, we have to redefine what makes a school. We have to rethink the legislation around daycares, for example. Everyone wants a daycare, but, often the rules and regulations surrounding daycares are so restrictive that it’s super difficult to accommodate them.”

Love acknowledges that “there isn’t one solution,” but says we need to take a page from the books of other high-density global cities around the world. “If you go to Manhattan, London, or Paris, you won’t find many four-acre schools, and we both know children still go to school in these cities,” says Love. “So, what makes a school needs to be thought through. But it’s more than that – it’s the whole accompanying social infrastructure to support density growth.”

Modern vertical schools – ones that grow upward as opposed to outward – have become commonplace in other dense global cities around the world. We’ve also seen the introduction of hybrid buildings that house both schools and residential units. “We need to further explore the possibility of building schools with residential units on top, especially in areas that are in high demand,” says Blonder.

In January 2022, Toronto developer Menkes Developments made headlines when it announced that it would build its first school inside of a condo. In collaboration with the Ontario government, which is investing $44M into the project, Menkes and the TDSB will create the new Lower Yonge Precinct Elementary School. As Toronto’s first podium school, the 455-student school will sit within the Sugar Wharf Development, a mixed-use condo project in the lower Yonge and waterfront neighbourhood. In a 2022 press release announcing the project, the Ontario government said that the new school could be replicated as an innovative solution to tackling the needs of Toronto’s working families in urban and high-density environments.

“Perhaps other developers will take a cue from Menkes, and we’ll see more of these in new builds,” says Sutton Balaban.

Toronto’s history of switching up the typical public school actually began decades back. In the St. Lawrence Market neighbourhood, for example, Market Lane Public School is one of the city’s newer public schools, having been built in 1992. Occupying a much smaller footprint than a typical Toronto elementary school, Market Lane is housed in a building complex that includes a community centre and apartment dwellings. While the school lacks a traditional field or baseball diamond, students have access to David Crombie Park right across the street (once, it was even accessible via an underground tunnel before leaking and flooding forced it closed), in addition to designated times at a local field down the street.

So, it’s been done before. As Colle suggests, there’s always the possibility of converting underused office spaces into schools. “Especially in the downtown core, you have so many empty office buildings,” says Colle. “So, we should start looking at these for public schools. However, you still need to have green space.” And – while schools could employ a similar strategy to that of Market Lane – sadly, precious urban green space is already limited.

“The public schools have schools that they used to lease out to private schools,” says Colle. “They’re now no longer doing that. We’ve got one school that used to be a Montessori school in the Avenue Road and Lawrence area that’s becoming a public school again. So, there’s that.”

But, while Love says sprawling properties may be a thing of the past, Colle says there is space to build new schools. He says he’s built two Jewish day schools in his tenure that filled up almost immediately. “It’s not a matter of space; it’s a matter of money,” he says. “There’s a lot of financial pressure. A school is probably $25-$30M, and it’s a long process. I have one school finally getting built now but it took 10 years to get there.”

With the rapid pace of immigration to Toronto, some would argue that we simply don’t have 10 years.

It’s About More than Just Schools

Of course, schools are just one piece of the social infrastructure needed to accompany rapid urban densification. “Beating the drum on social infrastructure is important in this climate,” says Love. “Social infrastructure gets very little air time.”

Density, he points out, is inevitable. “As the city welcomes new residents, we have to – by definition – densify,” says Love. “Point towers are a component of the solution. What we need are the four- to 12-storey buildings on major roads and thoroughfares with transit lines.”

But the physical infrastructure is just one piece of the puzzle, he stresses. “It’s part of a broader narrative; in addition to physical infrastructure, there is an ongoing need for social infrastructure and there’s often not an integration between planning and density – physical infrastructure – and social infrastructure,” says Love.

He says people need places to recreate, to worship, and to play sports. This means we need everything from parks to community centres. Of course, transit accessibility is also a given and – although it will take years (and years) — the City is moving forward to finally upgrade its subway system to move more in the direction of a world-class city.

Hopefully, its schools (and social infrastructure) will be next to follow suit.