The Residential Construction Council of Ontario (RESCON) held its third annual Housing Summit on Thursday. Sponsored by the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board, the Federation of Rental-housing Providers of Ontario, and STOREYS, the event gave more than a dozen real estate sector stakeholders from across the province an opportunity to speak freely about the housing crisis, including how we can start to solve it.

Speakers and presenters included everyone from bureaucratic bigwigs, like Premier Doug Ford and Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow, to market specialists like TRREB’s Jason Mercer, Altus’ Marlon Bray, and Smart Prosperity Institute’s Mike Moffatt, amongst others.

“We are at the crossroads of a generational crisis in housing, however, it’s unprecedented,” RESCON president, Richard Lyall, said to attendees in his opening remarks.

“There is little value in assessing blame and pointing fingers at this stage or at various levels. Our responsibility must be focussed on solutions. All levels of government, all private sector partners, and all housing stakeholders have a role to play.”

A Better Approach To Policy Reform

In speaking to housing-related policy and tax reforms implemented by governments to date, Marlon Bray, head of Altus Group's Ontario pre-construction and contract administration services, said that, at best, the measures we’ve seen advanced have been “haphazard” and “reactionary.”

“Right now, we’re wasting everybody’s time, and quite frankly, the housing crisis is not going to get solved where we are today or [with] anything that’s been proposed. We’re nibbling at the edges,” said Bray.

Something like the fed’s GST rebate “will move the market to a degree,” noted Bray, but it’s not enough.

Instead, Bray calls for more coordinated and thoughtful approaches to policy reform — one that’s sympathetic to the way the private development sector actually operates — and suggests other, more assertive measures, such as development charge rebates and property tax deferrals.

A Plea For The Feds To Step Up

Mayor Chow spoke during the mayors' panel portion of the summit about the importance of public infrastructure, stressing that there’s plenty of room for improvement with respect to how infrastructure is funded within municipalities.

The current system in place in Toronto, where infrastructure is funded entirely by property taxes, means that the city is limited with respect to investments in things like transit.

“What does that have to do with building housing? Well, a whole lot, because we can’t manage the housing if we don’t have the infrastructure, including transit,” said Chow. “A liveable city is not just building. It’s building things around it that makes the people that move in very happy.”

Chow’s sentiments surrounding public infrastructure were echoed by Paul Smetanin, President and CEO of the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis, who spoke in depth about the role of other levels of government in dictating the housing status quo within municipalities.

“We live in a country that doesn’t really believe in investing in infrastructure, or having an organized plan around infrastructure,” Smetanin said, pointing out that public infrastructure investment funding is currently 30% below where it should be to properly support growth.

In order to “promote sustainable economic growth” across Ontario, Smetanin said the federal government needs to “address imbalances” brought on by rampant population growth and ambitious immigration targets.

This means increasing their investments into public infrastructure, for one, but also taking stock of things like tax burdens and profit structures, both of which currently swing in favour of government fees and levies and do little in the way of incentivizing developers to build.

Taking A Cue From The Past For PBRs

Capping off the presentation portion of the summit was Smart Prosperity Institute’s Mike Moffatt, who suggested that the current tax system is “very poorly designed” when it comes to housing — and particularly when it comes to purpose-built rental development.

Purpose-built rentals tend to serve low-income end-users and are typically more environmentally friendly than single-dwelling homes, noted Moffatt. “That would suggest the tax system should have a fairly light touch on taxing lower-income apartment dwellers, apartment renters.”

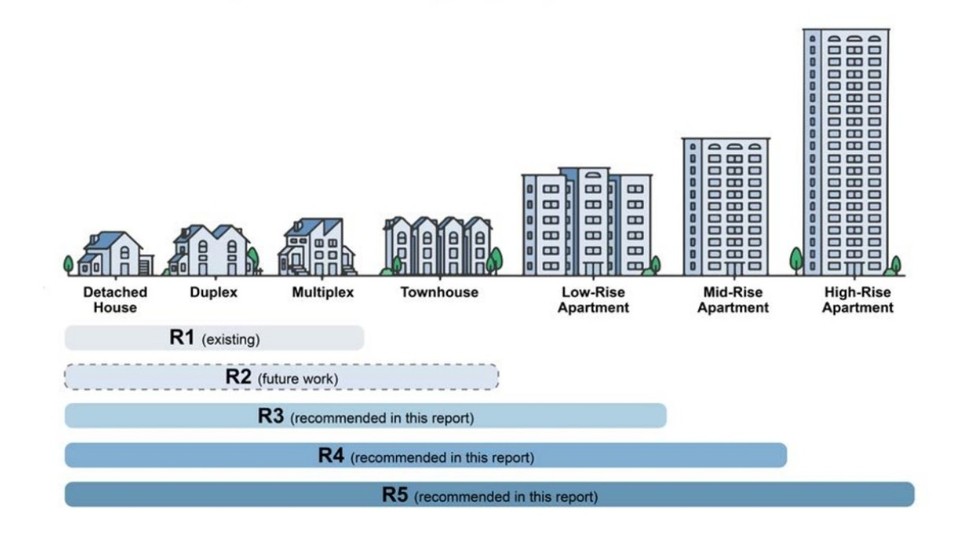

But on the contrary, high- and low-rise rentals tend to be taxed more heavily (on a square footage basis) than any other type of residential development in Toronto and across Ontario.

“Our tax system works against building the kinds of housing forms that we need, against building communities that help low-income renters, against our environment goals,” said Moffatt.

At one point, there was a system in place that was actually productive. Prior to 1972, Canada had an “accelerated capital cost allowance” (ACCA) of 10% for apartment buildings, which served to lower the cost factor for apartment projects, as well as the associated tax obligation.

At that time, there was another policy in place that allowed building owners to defer the capital gains taxes on selling a building, so long as they reinvested the profits into building more purpose rentals.

“It created a virtuous cycle, where the 10% ACCA creates the incentive to build a building, the deferral provisions created an incentive to sell the building and then build a new one,” said Moffatt. “It’s not a coincidence that we were building a lot more apartment buildings in the ‘60s and ‘70s with these kinds of provisions than we do today.”

It’s worth noting that bringing back such a framework would cost all levels of government around 2.2B over five years.

“This would cost the federal government some money, it would cost the province some money as well,” said Moffatt. “But the amount of new construction that we can unlock with this one simple tax change — that again, was a system that we had up until 50 years ago — is worth the investment.”

The full RESCON Housing Summit 3.0 can be viewed here.