In primarily residential areas, what does a typical development process look like?

Typically, the developer purchases land, seeks out approval from the local government for their proposal, demolishes the structures that occupy the land, constructs the project, and then rents or sells the project.

That's right, factually, but it's the wrong way of doing things, if you ask Glyn Lewis, the Founder & CEO of Renewal Development.

Renewal Development's mission is focused on that middle step, when homes that sit atop valuable pieces of land are demolished to make way for new construction.

What they do is simple: instead of demolishing homes, which are oftentimes still very livable, they will relocate the home to a new destination and give it a second life.

The Origin Story

Lewis took an "interesting" — in his words — journey to get to Renewal Development. It's one that can also be described as circuitous, with Simon Fraser University being the starting point.

"While I was studying Chemistry at SFU, I became awakened to the climate crisis," he says. "This was around 2005 when An Inconvenient Truth came out, and I remember watching that as a student and thinking that this climate crisis was going to be the most important issue in our lifetime, and I wanted to commit myself to helping to address it."

He subsequently shifted his degree from Chemistry to Environmental Chemistry. At one point, he also took a program focused on socially and environmentally-responsible community development. However, he eventually realized that research wasn't the way for him to help and began looking for another way.

He landed on politics, and specifically in the United States, where he was involved in the 2008 presidential campaign of Barack Obama, as a Campaign Organizer. Afterwards, he stayed in politics but returned to Canada, eventually starting New/Mode, a company that builds software for political movements, with Steve Anderson.

Then came the lightbulb moment.

"About four years ago, my sister was living in this really charming 1910's home in Esquimalt, just outside of Victoria, and it was acquired in a land assembly by a developer. She really loved her home, her and her partner took really great care of it, and it was really sad to see it slated for demolition. But instead of allowing the developer to tear it down, she worked out a deal where she physically picked it up and moved it to another property they purchased just north of Sooke. When she did this, it really kind of opened my eyes to this incredible model of sustainable development."

Renewal

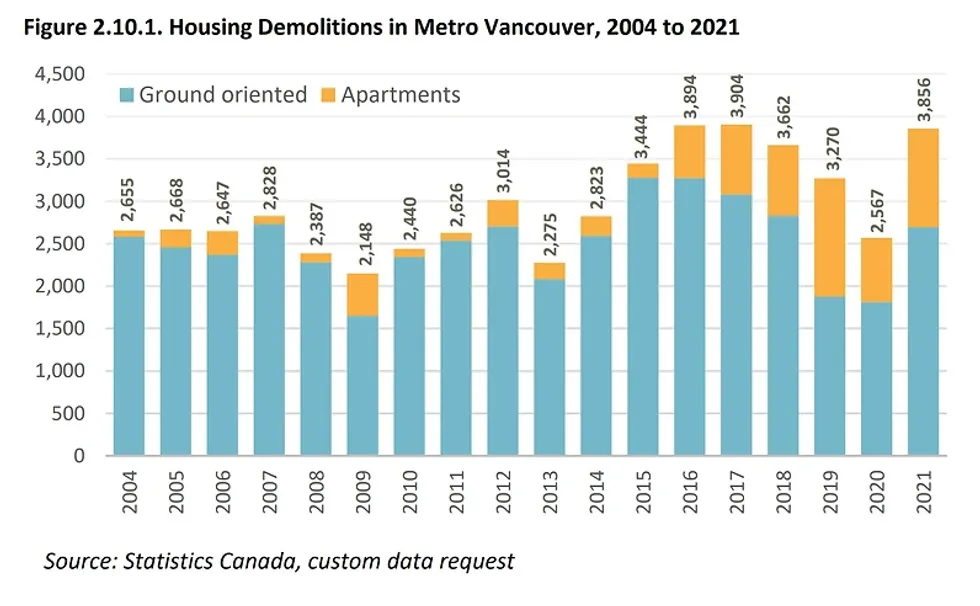

Lewis says that, in Metro Vancouver, approximately 3,000 homes get slated for demolition each year — we're "one of the demolition capitals of the world, on a per capita basis," he says — and results in a third of Metro Vancouver's landfills being full of construction and demolition waste.

Of those 3,000 homes, around 700 are perfectly good homes that just happen to be in the wrong place, so to speak.

"I created Renewal to rescue, relocate, and repurpose more good homes," says Lewis.

Once a development is in process and reaches the demolition stage, Renewal steps in — they're typically the ones that reach out to developers — and takes on the role that would traditionally be filled by the demolition company. Renewal visits the site, assesses it, then gives the developer a price to clear the site by the developer's desired date.

How the site is then cleared, however, is up to Renewal, and this is where they do their thing.

"We simply have a mix of a solution. What happens is if we're looking at a 10-home land assembly, let's say six of the homes we can't move — they're either too old, or too big. We will demolish those six homes, through the conventional means of abatement, demolition, taking the debris away, recycling it. The other four homes, with good bones and are well-maintained, we will physically relocate them to a community that needs housing."

The homes that are suitable for relocation are primarily bungalow and rancher homes that were constructed in the 1950s and 1960s, says Lewis, who adds that they're suitable because of their typical size and because they were typically built with first-growth lumber, which is very dense and strong.

How relocation benefits developers — the "value proposition," in business jargon — is that "it's cost-comparative to demolition, it's timeline-comparative to demolition, and yet we're saving 40% of the homes slated for demolition," Lewis explains. Furthermore, he says, "not only are we saving 40% of the homes, but they're going to communities that need housing."

"There's a marketing and community benefit to the developer or homeowner to do the responsible removable solution," Lewis says. "Ultimately, my goal isn't to be a demolition company. I'm not interested in being a demolition company, I'm interested in being a responsible removal company. I'm trying to save and move as many homes as I can and I will demolish homes that I can't."

How To Pick Up A Home And Move It

At this point, it's reasonable to ask, "Do they really pick up a home and move it, or is it more a deconstruction then reconstruction?"

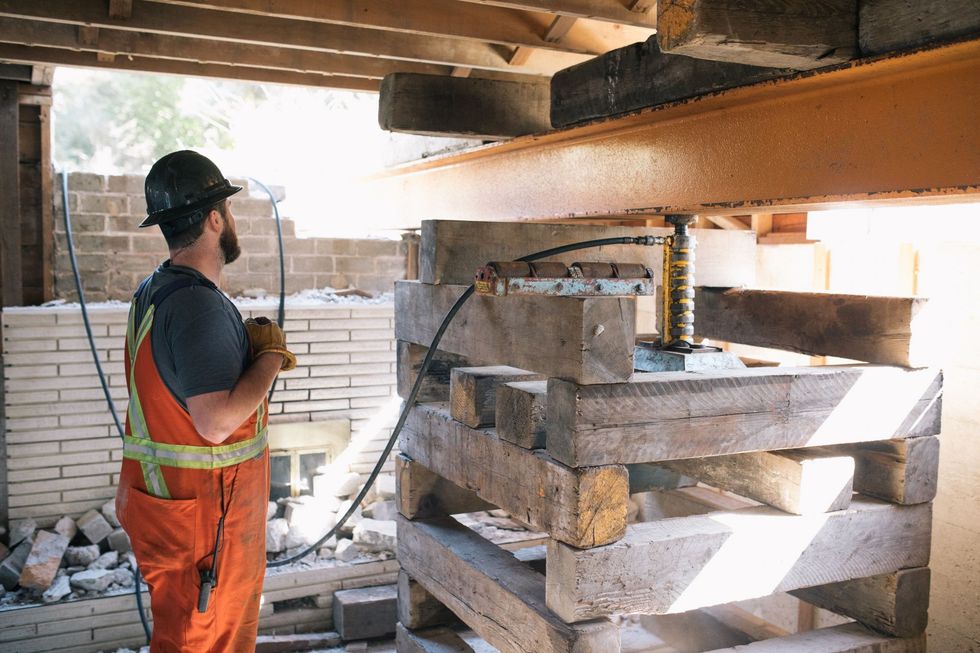

"Essentially, what happens is these steel beams go underneath the floor joists — the base frame — and then [the home] gets lifted through this synchronized hydraulic jacking system," explains Lewis, whose company partners with Nickel Bros to do the move.

Any part of the home below ground, such as the basement, can't be picked up, while the house is then put onto a truck — that's why home's that are too big can't be relocated. The truck then transports the homes to a barge — 90% of the homes Renewal relocates are moved on water — before the truck then brings the home to its new location.

After the home arrives as its new destination, Renewal then acts as a general contractor and modernizes the homes.

"We will upgrade the windows, we'll upgrade the insulation, we'll convert the gas furnace to a heat pump, and we'll do some cosmetic upgrades so that the home is a really beautiful and renovated building with great bones that's going to be a great home for many decades to come. We never just deliver a home as is."

In April, Renewal Development did all of this for 10 homes (out of 59) that were set for demolition as a result of the Inlet District project by Wesgroup Properties in Port Moody. In that case, Renewal also added in basement suites to nine of the homes, which were relocated to Sechelt on the Sunshine Coast and purchased by the Shíshálh Nation, as part of Phase One of the Nation's Selma Park subdivision project. For the project, Wesgroup also reallocated its $35K per home demolition budget to the Nation to lower their relocation costs.

Lewis says most of their relocations so far have seen the homes moved to remote First Nation communities, where there is a dire and tragic need for housing.

The Current Paradigm

Housing solutions can also be climate solutions, and that's at the core of Renewal Development.

"Why I created Renewal was to address the incredible amount of waste going to our landfills, but also to try and help impart a solution towards addressing climate change. We know it's more responsible, from a climate perspective, to not tear down trees to build a new home, or to mine all the copper needed for the wiring, or to extract and create all this plastic for all the plumbing."

In other words, this is the way things have been done, but it's not always good to be set in your ways. This is not a case of fixing something that isn't broken.

"My thesis is that demolition should be the last option, not the first. We need to move away from this demolition-first paradigm. We've been living in it because it's understood and it's the easy thing to do. We need to move away from this demolition-first paradigm."

When asked what can be done to help encourage more responsible demolition, Lewis points to several things on the part of municipal governments. One such example can be found in the City of Victoria, which is currently in the process of implementing a bylaw that charges demolition permit applicants a $19,500 fee, which can only be refunded after the applicant salvages the wood from their demolition.

Another thing any local government can do, Lewis says, is introduce a simple one-page mandatory form for demolition permit applicants asking whether they've contacted a responsible demolition company. This forces developers to look into those options and saves responsible demolition companies from having to reach out one by one to convince developers to do the right thing.

"I think that anytime you try to change a paradigm, it's not going to be easy," says Lewis. "There's a very entrenched mindset, there's a very entrenched culture, there's a very entrenched set of policies, that favours demolition, which is not the right thing to do. We shouldn't be filling up our landfills with perfectly good homes, especially when you have housing crisis."

Lewis views this "responsible demolition" industry as a nascent industry, which is currently occupied by companies like Renewal, as well as other companies that do deconstruction, such as Unbuilders, and companies that make homes slated for demolition available as temporary housing, such as the Journey Home Community.

"I think this is a nascent industry, I think this is an important industry, and I think you're only going to see this industry growing and strengthening over the next two to four years," says Lewis. "This demolition-first paradigm has to end, and I think it will end. I think five or 10 years from now, it'll be a relic."