The discussion around development cost charges (DCCs) continues to gain momentum in British Columbia as a result of the letter-writing campaign a group of prominent developers launched in September, targeting the forthcoming rate increases for DCCs paid to the Metro Vancouver Regional District (MVRD).

That letter-writing campaign got those developers a special meeting with the MVRD Mayors Committee on October 17, where many voiced their concerns regarding the potential impacts on development and resulting effects on housing affordability.

The crux of the issue is this: the Metro Vancouver region is seeing significant population growth, the MVRD needs money for infrastructure projects that support that growth, and charging DCCs on new construction is one of the traditional ways of securing funding. From the perspective of developers, many of their costs are increasing, the presale market has been tempered as a result economic conditions, so many are having difficulty just getting to the construction stage, let alone making a satisfactory profit.

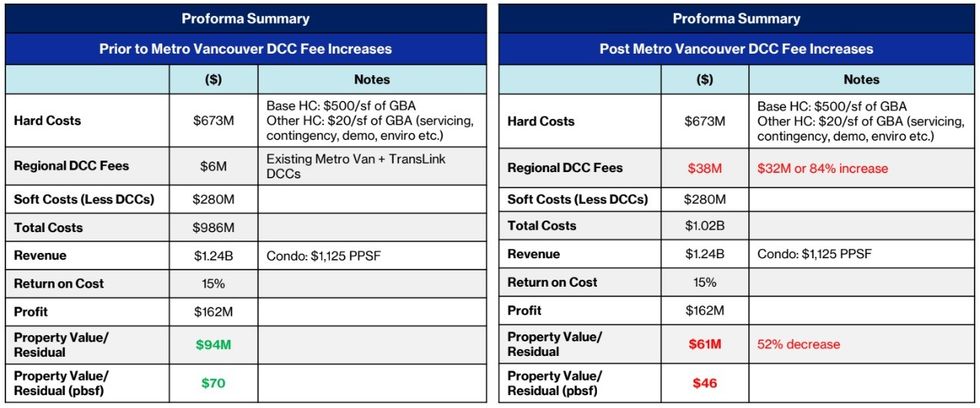

The higher the overall project costs are, the higher the prices will have to be, because developers — like other kinds of businesses — have to make a certain amount of profit to satisfy their lenders, investors, and themselves. As such, the concern with the DCCs is that the increases are very significant (double or triple the existing rates, in some cases), they are coming at a time when the economics of development are already tough, and that at least some of the burden will ultimately get passed on to end users, whether it be purchasers or renters.

Last month, Coriolis Consulting Corp. published an analysis of the MVRD DCC increases and their potential impacts on housing development and housing prices. The analysis was prepared for the MVRD and Coriolis said the increases "are significant and will lead to increased construction costs for new development projects," plus one (or a combination) of three things: a reduction in the land values of development sites, a reduction in profit margins for new projects, and an increase in housing prices.

Land Values

For developers, most of their costs can be estimated with decent precision. The hardest cost to estimate is often the cost of the land and whether it is worth acquiring, relative to the profit they can achieve. To answer this question, developers often conduct a pro forma analysis to identify the residual land value. Starting from the end with the projected revenue, all of the other inputs — permit fees, construction costs, allotted profit margins — are then subtracted, leaving the residual land value, which is the maximum price they can pay for the land to achieve the projected revenue.

Currently, developers are not as optimistic about projected revenues as they once were, while various costs are getting much higher, which reduces the maximum amount they can pay for a property. Every purchase requires somebody to sell, however, so while a developer can lower their bid for a property, the landowner may not be inclined to sell. If it is a single-family home, the price doesn't just have to make financial sense, it has to be enough that the family is willing to relocate. If it is a land assembly, as is often required, then it becomes exponentially more complicated. Many believe this year's change to the capital gains tax have complicated that even further.

If this occurs, assuming that the residual land value is relatively accurate and not drastically different from what another developer may find, then that property is essentially removed from the pool of available development land. If that becomes commonplace and the supply of development land is reduced, while demand remains strong as a result of our housing crisis, then the price for land goes up. If the developer is willing to pay the higher price and the landowner agrees to sell, then the project may proceed, but with a reduced profit margin. That is not always possible, however, as a result of lender requirements, so what is more likely is that end users — the purchaser or renter — is charged a higher price.

"What we've already seen is land values fall because sales prices are off for new home sales and volume is off for new home sales," says Robert Bruno, Executive Vice President of Polygon Homes, one of the developers that submitted a letter to Metro Vancouver. "So land values have already started to adjust for development sites. The problem is that, in some cases, they've adjusted so far that the landowners are simply saying 'I have no motivation to sell.'"

"Anything that pushes land value too low will actually reduce the available sites for housing," he added. "I've been [at Polygon] for 22 years and I've never seen a cost environment like we have today. Our costs are the highest that we've ever seen and we don't forecast them coming down in the near-term."

Profit Margins And Housing Prices

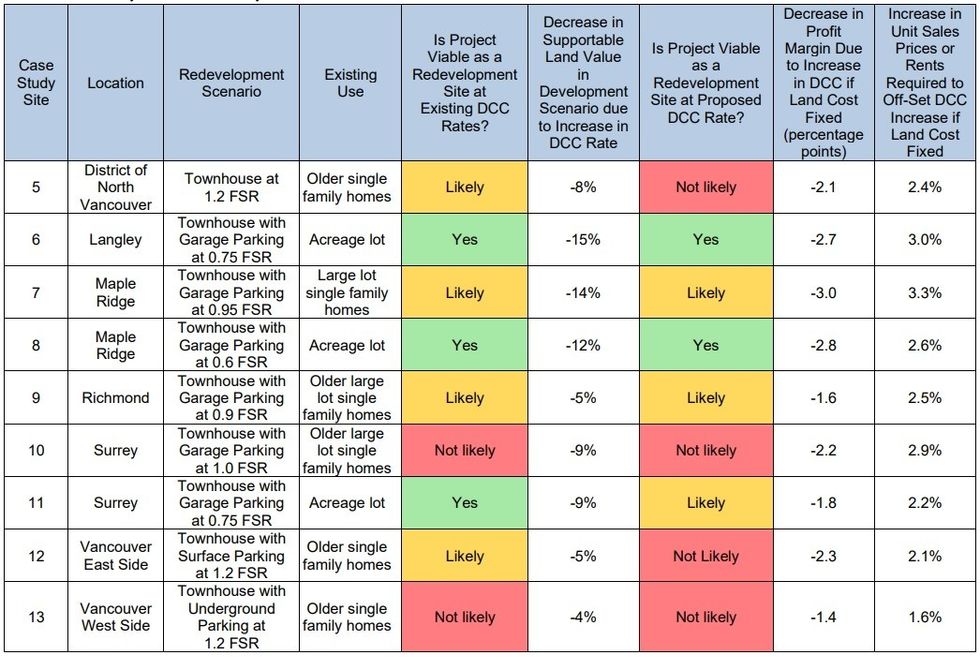

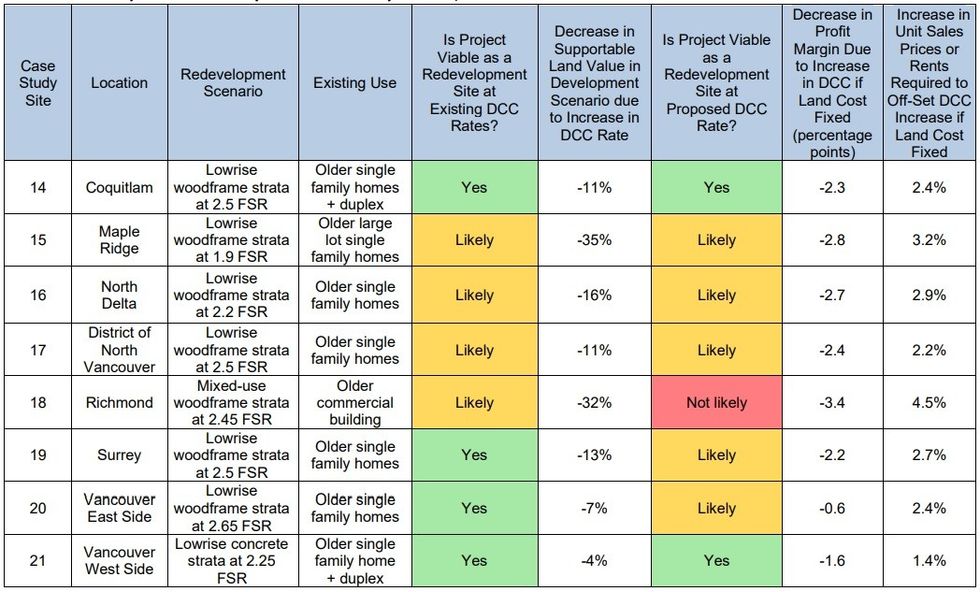

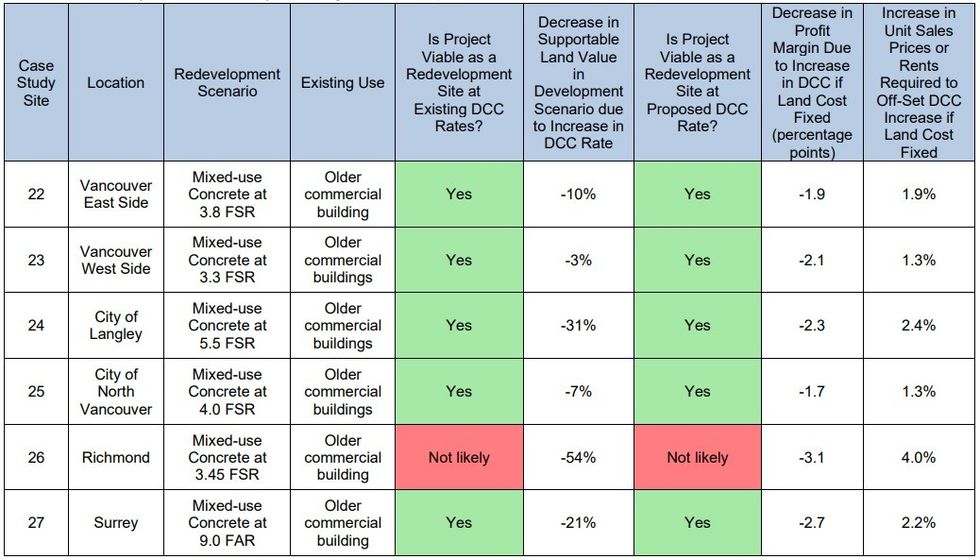

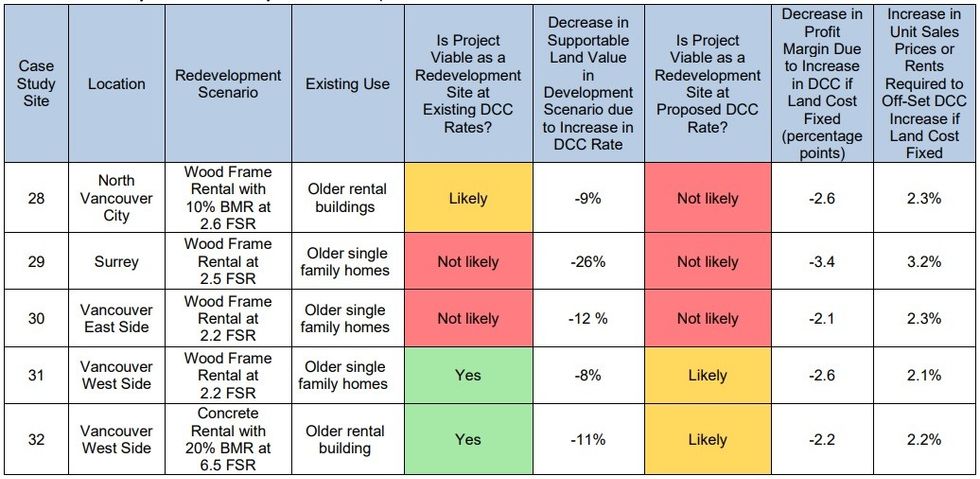

Coriolis' analysis was based on 41 case studies that consist of a diverse range of hypothetical projects at real-world locations across Metro Vancouver. Factoring in the current use of the property, the floor space ratio of the redevelopment plan, and the current Metro Vancouver DCC rates, Coriolis projected the profit margins of the projects.

Profit margins over 12% for rental projects and 15% for strata projects were deemed to be "viable," projects with a margin between 10% to 12% for rental and between 10% to 15% for strata were deemed as "likely viable," and any project with a margin below 10% was categorized as "not likely viable." They then swapped in the 2027 DCC rates — the rate increases will be implemented in phases on January 1 of 2025, 2026, and 2027 — to see how they affect margins and viability, as well as the increase in sale price or rent that would be needed to offset the impact.

For single-family subdivision projects, Coriolis found that the main impact would be a 1% to 4% reduction in development site land values, with projects remaining viable and a minimal impact on housing prices. For strata townhouse projects, Coriolis found location to be a key factor, due to the difference in land values. These projects are already "marginal" at the current DCC rates, so Coriolis concludes that the new DCC rates will likely result in a smaller pool of development sites and price increases of between 2% to 3% for end users, depending on location.

A similar impact is expected for low-rise strata buildings. "Our case study analysis indicates that, in most locations in the region, the land value supported by 4 to 6 storey strata apartment development is either similar to or lower than the value supported by the existing use of the property," said Coriolis. "So, in most cases, the increased Metro Vancouver DCCs cannot be passed back to landowners." Landowners won't be inclined to sell, in other words. As a result, Coriolis expects the primary impact to be a reduced pool of development sites, a slower pace of new supply, and a price increase of between 2% to 3%.

High-rise strata projects, however, would be impacted in a different way, said Coriolis. Land values may be negatively impacted, but most development sites will likely continue to be viable and there will likely be little impact on the pace of new construction. However, the increased DCCs could have an indirect effect on affordable housing, as it would likely result in a "reduced ability of highrise strata apartment rezonings to provide contributions to amenities or affordable housing because of the impact on the value of the additional rezoned density."

A key factor and exception is whether the development site was acquired before the new DCC rates were announced, Coriolis said. For sites that were purchased prior to the announcement, "the developer would likely face reduced profitability if they proceed in the short term (our case study analysis indicates a potential impact on project margins in the range of 1.9% to 3.1%)" and this "would likely result in some highrise projects being delayed until market conditions change" — something we're already seeing.

For rental projects of various sizes, financial viability is also already currently "marginal." The new DCC rates could potentially reduce the viability a bit more, landowners would again not be inclined to sell, so the pool of development land will become smaller, the pace of new supply will slow, the low supply will raise rents for existing stock, and new stock will likely see an increase in rent of between 2% and 3%.

Asked to assess Coriolis' findings, Bruno and Wesgroup Properties Senior Vice President of Development Brad Jones both independently said they agreed with the overall conclusion that the pool of available development sites would be decreased and housing prices would be increased, but have questions about some of the details, primarily because Coriolis did not disclose their assumptions regarding construction costs and sale prices. "To be honest I have no idea how they reached this conclusion," said Jones, regarding Coriolis' finding that the viability of high-rise strata projects wouldn't be affected. "This is not what we are seeing in our business."

Metro Vancouver

Coriolis prefaced their analysis noting that DCCs are just one of many economic factors that affect development and that there are many other factors that were not included, such as the suite of provincial legislation that local governments began implementing this year. Metro Vancouver's stance is that they take the findings about the potential impact on housing prices seriously, but that the context is important.

"It's a point-in-time look from June 2024 where they looked at 41 case studies across the region and they utilized 2027 fully-implemented DCCs," said Heather McNell, Metro Vancouver's Deputy Chief Administrative Officer of Policy and Planning, in an interview with STOREYS on October 31. "It's important context because economic factors have changed a lot, even since June."

Some of the economic factors that developers are dealing with also apply to Metro Vancouver and their infrastructure projects, which developers also recognize. For each of their infrastructure projects, Metro Vancouver conducts of assessment to figure out which portion of the project can be attributed to growth. As one example, McNell said that about 8% of the Iona Island Wastewater Treatment Plant project is attributed to growth, meaning 8% of that project is funded through DCCs. The growth-related portion can vary from project to project, with some as high as 99%.

"I think we've had really clear direction from our Board to accelerate the principle of growth paying for growth," added McNell. "We only have limited tools to pay for our capital program. The reality is we have a large infrastructure capital program that is necessary and about 50% of that is growth-related. The Board has been clear that for the growth-related portion of projects, DCCs should be paying for those, while existing ratepayers pay for the non-growth portions of those projects."

As part of their letter-writing campaign, the developers have asked for more in-stream protection and for DCCs to be collected at a later stage of the development process. McNell said that those changes are under the jurisdiction of the Province, but that Metro Vancouver is open to the ideas and working with the development community on advocating for those changes, as well as advocating the federal government for more infrastructure funding.

"What we could do is convene all of the City Managers and CFOs and have a discussion with them about why they collect when they do and if there's an openness to [collecting at the end]," said McNell. "Maybe it's just Metro Vancouver DCCs that are deferred to later in the process. There are some things there that need to be explored there around security, but definitely we're open to exploring that and having ongoing dialogue with the development industry."

Metro Vancouver will also be working on several other things related to the DCC program.

"What we're doing is, first of all, looking at expanding our affordable housing waiver," said McNell. "Then we're looking at making sure we have updated our housing types for the DCCs. The new provincial legislation has changed the definition of things like single-detached units and Metro Vancouver and others are going to have to grapple with what that means for the DCC programs. Then we're also gonna have to grapple with the fact that we've been growing faster than we had thought, so we have to update population and dwelling unit projections for our DCC program and make sure it's right-sized as well."

Various developers STOREYS has spoken to about the issue recognize the predicament Metro Vancouver is in and said that although their letter-writing campaign was addressed at Metro Vancouver, the issue is not specifically the Metro Vancouver DCCs.

"If we want to ensure long-term housing supply, we have to stop the layering of fees," said Bruno, of Polygon. "Individual fees — we can discuss that. If Metro Vancouver has more of a right to a fee than others, that's fine. It's not about a single entity or a single fee. It's about the cumulative effect of design obligations, public art fees, municipal DCCs, other municipal charges, servicing requirements, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. This is all on the back of a construction environment that is at the highest that we've ever seen. Then you look at the market and the market is slower. Presales are slower, prices are flat at best, and if you really want to get your presales in order to meet your requirements for the bank, you're looking at probably launching at prices lower than where you need to be at to achieve an acceptable margin."

"At some point, the new homebuyer can only afford to pay so much, and if you layer on cost after cost after cost, the cost of producing something is actually higher than what anybody can afford," he added. "Therefore, no housing supply can get created. That's my biggest concern. We're already struggling to get our margins working at Polygon, at Wesgroup, at Beedie, the Onnis of the world. The bigger developers, they have these experienced machines and they have land bases that they perhaps bought at historical costs, so you know what, we're gonna continue pushing things through because we have a machine. But for some people, it's just gonna be full-stop because they won't be able to move forward, the banks won't finance them, the presale market is not there, or you simply don't have the initial equity required to put into these deals. What happens then?"

- Inside The Cost-Profit Analysis Of Three-Bedroom Units In Metro Vancouver ›

- Wesgroup SVP Of Development Brad Jones On The Challenges With DCCs, REDMA ›

- Canada Housing Infrastructure Fund Launches With Requirement For DC Rate Freezes ›

- Inside The Financing Challenges Developers Are Facing With Rental Projects ›

- Metro Vancouver To Receive $250M From Feds For Iona Wastewater Plant ›

- STOREYS’ Policy Of The Year: Development Charges ›

- Metro Vancouver Proposes Expansion Of DCC Waivers Program ›

- Metro Vancouver Proposing Extension Of DCC In-Stream Protection Period ›

- Inside The City Of Coquitlam As Developers Rush To Get Permits ›

- Why Constuction Costs Are Higher In Vancouver Than Toronto ›

- BC Extends In-Stream Protection From Metro Vancouver DCCs To Two Years ›

- Governments Are Turning The Corner On DCCs. Will It Make A Difference? ›