The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) updated its housing supply gap estimate this month, revealing that the country will need around 3.5 million housing units by 2030 “over and above what is already projected to be built by that time” in order to restore affordability to 2004 levels.

Despite the directive nature of this estimation, economists are warning that ‘ramping up’ supply alone isn’t going to solve the housing crisis — and it certainly isn’t the answer to Canada’s housing affordability woes.

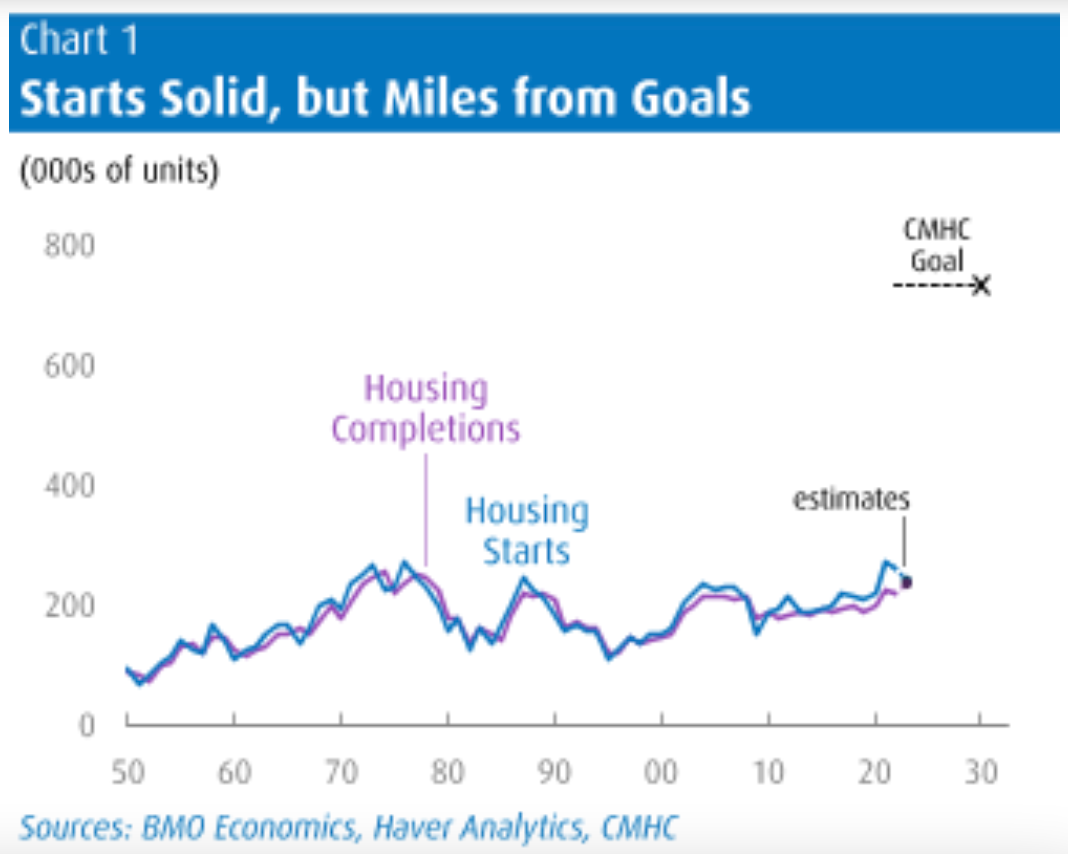

From the jump, there’s the issue of a building sector that’s already overextended and understaffed. In a report from Friday, BMO economists Douglas Porter and Robert Kavcic break down CMHC’s new (and widely cited) estimate, noting that it translates to around 500,000 additional units per year.

“That’s above and beyond the recent pace of housing starts of roughly 250,000 annually — so they are essentially saying it will take a tripling of the pace of homebuilding to make housing affordable,” says the report.

“To put it in perspective, the all-time record annual high for Canadian housing starts is 273,000 way back in 1976, and they nearly got back to that level in 2021. In other words, the bar is not going to be approached, let alone cleared.”

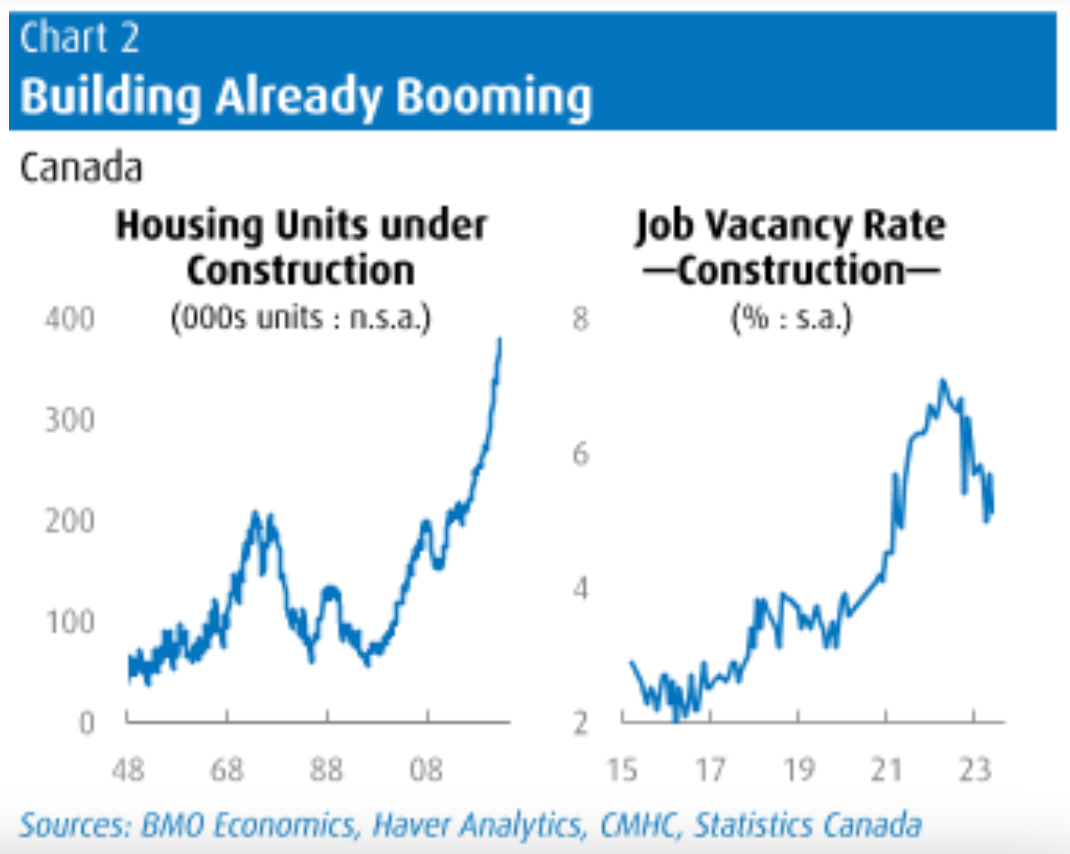

And then there’s the unprecedented economic status quo. For builders and developers, financing costs have surged in recent years. Even with the upward trajectory of rental rates, “current cap rates don’t ‘pencil’ well after 475 bps of tightening by the Bank of Canada,” says the report.

“The implication is that builders are finding it more difficult to pre-sell new developments, which is usually a hurdle to receive financing and break ground on construction. Suffice it to say that these tougher conditions are not going to just go away overnight.”

BMO’s report then digs into the challenges presented by CMHC’s methodology, noting that the housing affordability from the early 2000s “took place in a world we can’t, or wouldn’t want to, totally recreate.”

“That period followed a decade-long bear market in housing, particularly in Ontario, where nominal home prices took more than a decade to recover declines. The 1990s recession saw double-digit unemployment in the province, a large overhang of housing inventories, and many industry participants go out of business,” says the report.

“Meantime, population growth trends were starkly different leading into the early 2000s, with growth in the 25-40 age cohort (indicative of incremental housing demand) in outright decline for 13 years through 2006 (coincidentally 2003 was the absolute low). The demographic forces couldn’t be further from those conditions today, with millennial demand peaking and supplemented by robust international immigration flows.”

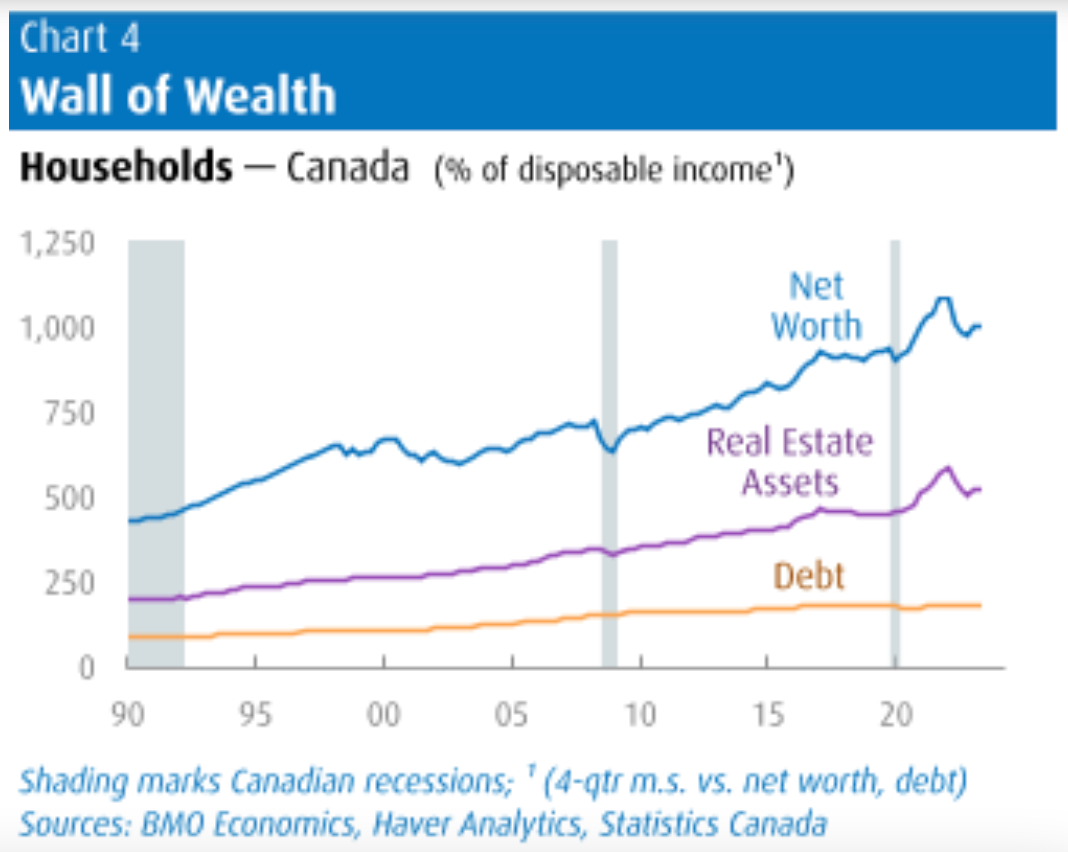

Friday’s report also points out the tremendous rise in household wealth in the past 30 years, which has given rise to “relentless strength in investment demand.”

“Household assets are more than six times the size of debt. And while real estate appreciation has accounted for a good portion of the enormous rise in household assets, financial assets have also risen rapidly and account for a bit more than half of the total,” notes the report.

“This run-up provides households with plentiful financial firepower, and at least some of this deep well is finding its way into real estate investments, whether on an individual basis, in partnerships, or through institutional channels.”

Canadian housing markets are on track to soften in the coming months, but nonetheless, an end to the housing crisis is a long way off. Many of the barriers to getting more housing off the ground quite clearly lean systemic, and are yet to be effectively corralled by policymakers.

“It’s good to have lofty aspirations for homebuilding given the tightness in Canada’s housing market and rapid-fire population growth. But we can’t be led down a blind alley of wildly unrealistic targets, then, expect a major push to build will alone solve affordability strains,” conclude Porter and Kavcic.

- 'No Silver Bullet': Economists Recommend Targeted, Coordinated Policies To Solve Canada's Housing Crisis ›

- Canada’s Housing Crisis 'Worse Than Perceived' As NPRs Continue To Be Undercounted ›

- Canadian House Prices To Fall 10% In 2024 As Economy Slips Into Recession ›

- Population Growth Is Outpacing Housing Completions By 40% ›