A new report from TD Economics warns that Canada's housing supply gap could widen by 500,000 units within the next two years if immigration continues at its current pace.

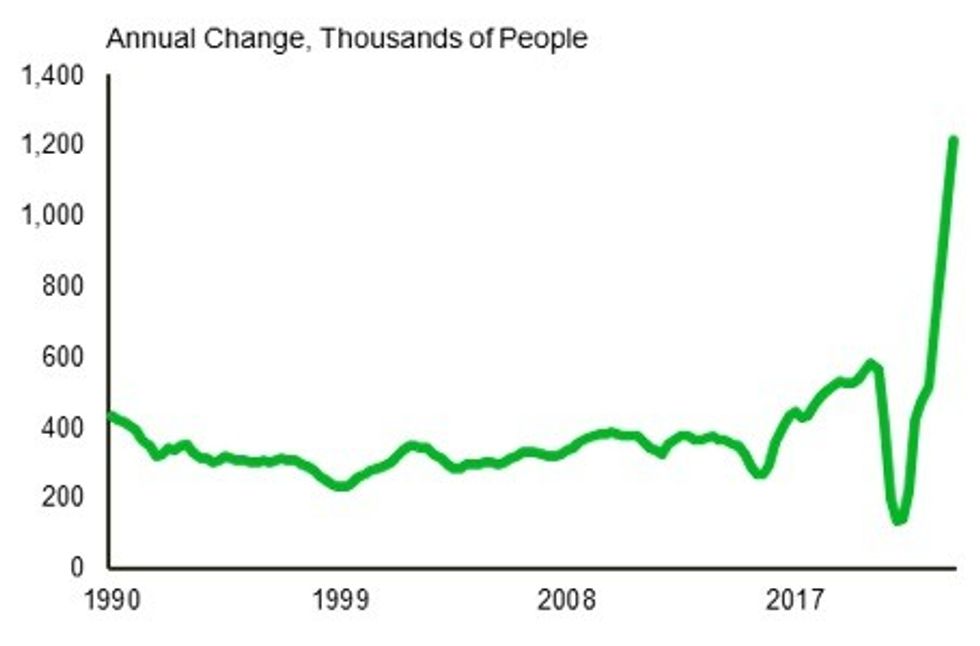

Over the past year, Canada's population grew by 1.2M people -- more than double the pace seen in 2019 and the years preceding -- 60% of whom were non-permanent residents, such as refugee claimants or those with a work or study permit.

The remaining 40% were welcomed under the federal government's elevated immigration targets, which aim to attract another 465,000 permanent residents in 2023, 485,000 in 2024, and 500,000 in 2025.

The group of non-permanent residents is an essential part of Canada's immigration strategy, which seeks to solve shortages in the workforce and attract skills in key sectors, such as healthcare and technology.

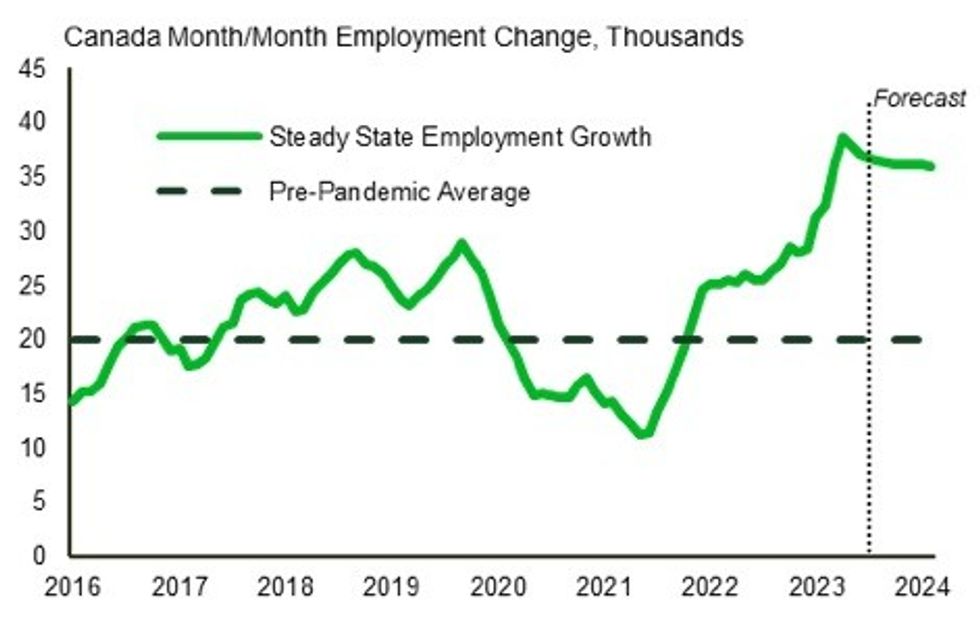

In the labour market, the benefits of the population boom are already apparent -- monthly job growth has averaged around 40,000 since the spring of 2022, while the monthly trend observed from 2010 to 2019 was 20,000.

However, while the influx of non-permanent residents bolsters the labour market and supports economic growth, the report cautions it could strain other segments of the economy, particularly housing affordability.

With starts trending downwards and supply levels low, assessments of Canada's future housing stock, in both the ownership and rental markets, were already pointing to worsening affordability prior to the surge in newcomers.

Now, as declining construction levels coincide with the growing population, the report estimates that from 2023 through 2025, Canada’s housing supply could fall short of demand by approximately 215,000 units.

But, with several signs pointing to another one-million-plus person year, that demand-supply gap could instead double over the same timeframe.

"We estimate that a continuation of a high-growth immigration strategy would widen the housing shortfall by about a half-million units within just two years," the report warns.

"Recent government policies to accelerate construction are unlikely to offer a stopgap in this short time period due to the natural lags that exist in adjusting supply."

Even if Canada's population growth slows back towards its long-term average, there would still be a shortage of 150,000 units come 2025. As such, a "meaningful improvement in affordability will likely remain elusive,” the report fund.

Dr. Mike Moffatt, Economist and Assistant Professor at Ivey Business School, tells STOREYS that without getting shovels in the ground today, the housing-related social issues that have worsened over the last several years, like increased homelessness and refugees sleeping on the streets, will continue to deteriorate.

“The worse it gets the harder it is to dig ourselves out of that hole,” Moffatt said. “We need to get on this. The situation is getting worse.”

As the report notes, governments have been attempting to remove barriers to building more housing. For example, in Toronto, the City has approved changes that promote density, including allowing multiplexes in all neighbourhoods, while the Province of Ontario has reduced development fees.

But, even with the changes, construction timelines are such that it would take years for completions to catch up. And, even if the changes do lead to record completions -- an "aggressive assumption," the report states -- the housing gap will still persist if Canada continues to see annual population growth over one million.

Although the task seems futile, Moffatt says there is a lot more that can be done, by all three levels of government, in order to speed up the pace of housing construction.

At the municipal level, cities can work to speed up the approvals process. On a provincial level, in Ontario, the government can implement the remaining recommendations laid out by the Housing Affordability Task Force. For its part, the federal government can remove the HST and GST on new rental buildings.

“There’s a lot more we could do. It’s just a matter of getting the political will, and having politicians recognize the crisis for what it is,” Moffatt said. “Frankly, I’m stunned they’re not doing more. This housing system isn’t working well for anyone.”

Making matters worse, the report says, is that the population surge is a “textbook demand shock” — newcomers become consumers, and the rapid rise in demand overwhelms the economy’s ability to respond.

Without a coinciding increase in productivity, which “has not been Canada’s forte,” any persistent demand shock is addressed by higher interest rates, which, in turn, erode affordability and raise the cost of construction.

“Adding up the pieces, concerns around affordability will not likely abate in the foreseeable future. This cautionary tale of housing pressures can be applied to many other parts of society, from social systems to health care to physical infrastructure,” the report reads. “Everything needs balance.”

The report stresses that population growth is both a good thing and a necessity given Canada’s aging population. But, if it happens too fast and newcomers can’t be readily absorbed into the social end economic fabrics, the benefits begin to erode.

Part of the solution lies in removing workplace barriers, like credential recognition for medical professionals and engineers, allowing those already acclimated in Canada to enter the workforce. This would reduce external demand for workers — although they will still be needed — therefore easing pressure on other areas of the social system, like demand for housing.

“A lot can be done to better integrate both new and existing Canadians so that people can reach their full potential. It can’t just be a matter of bringing in an unchecked amount of people to take the lower paying jobs on offer,” the report reads.

“To set the country up for success, policy needs to be balanced in ensuring an appropriate infrastructure is in place to bring the best out of workers and families. This way the economic pie won’t just grow in size, but the quality will increase as well.”

To Moffatt, the worst-case scenario is that Canada’s historic tolerance towards immigration, and wide-held recognition of its benefits, declines as a result of the housing strain.

“My real fear is that [that tolerance] starts to crack, and people blame newcomers because their kids can’t find a home or because the rent is too high,” Moffatt said.

“I would absolutely hate to see that happen. And I think there is a real risk if all three orders of government don’t start to take this crisis seriously.”