Canada’s oldest Baby Boomers turn the big 8-0 next year. Though the country’s aging population is a long-understood reality, the stats put this demographic shift into perspective: The population of Canadian seniors (65+) is projected to swell to nearly one quarter of the overall population by 2040, according to the Government of Canada.

Generally, Canada’s 65+ set is healthier, living longer, and enjoying more financial freedom than previous generations. They're active, in-the-know, and perhaps even still employed. With that said, Canadian seniors represent an incredibly diverse demographic, with a wide range of needs and financial resources. For those in their later years, housing options can range from remaining at home independently or moving in with younger family members, to relocating to seniors' lifestyle communities, retirement homes, or – eventually – long-term care (LTC) facilities.

Adequately accommodating the housing needs and wants of older Canadians is inevitably complex and multi-layered. While there’s no one-size-fits-all approach, one thing’s certain: It’s time to get serious about housing seniors of all economic backgrounds.

Regional Differences

In 2017-2018, most Canadian seniors lived in population centres (79.5%). The Atlantic provinces (47.5%) and northern Canada (42.1%) saw the largest share of seniors living in rural areas. In 2021, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and British Columbia saw their proportion of the population aged 65 years and older higher than Canada overall.

“The population is aging more rapidly in certain parts of the country, particularly in Atlantic Canada,” Jordann Thirgood, Manager, Public Policy, CSA Public Policy Centre tells STOREYS. “For example, as of 2021, 23.6% of Newfoundland and Labrador’s population was aged 65 and older, compared to the national average of 19%. This is important because provincial government in this region will face higher costs to deliver healthcare and other public services, but only receive funding from the federal government on a per-capita basis that does not account for population age.”

Furthermore, Thirgood says that the population is aging quicker in rural Canada than in urban centres. “This raises important questions about how we build cities, and the ability for older Canadians to get around and engage with their communities in remote and rural areas,” says Thirgood. “Between 2016–2021, the proportion of the population aged 65 and older grew by 1.9 percentage points in urban centres, compared to 3.1 percentage points in rural areas.”

Changing Preferences

Compared to the past, a high number of Canadians have expressed their desire to age in place at their current residences. According to the Government of Canada, 92.1% of Canadian seniors (aged 65+) live in private dwellings in the community – many, with no plans to leave. “There is a growing preference among Canadians to remain within their home and community as they age rather than moving to an institutional care setting,” says Thirgood. “However, there are several supports, services, and legislative changes that need to be considered to better enable aging-in-place. For example, the home care services sector is largely underfunded and experiencing human resource shortages, homes and communities are not always built with all abilities in mind, and social isolation and loneliness are a significant concern for those living alone.”

A 2022 Ipsos survey revealed that nearly all Canadians aged 45 and older (92%) want to age at home, but only 12% said they could afford the cost of a personal support worker (PSW). According to our research, the cost of a PSW in Ontario currently ranges from about $28 to around $38 per hour. For those who require full-time care, remaining at home may therefore not be economically feasible.

In addition to potential at-home care, homes may require physical modifications to account for changing abilities. “Ideally, you want all the essentials – a bathroom, bedroom, kitchen, and laundry – on one floor,” says Darrell Booker, a Toronto-based realtor and owner of DH Group, a contracting company that specializes in accessibility modifications. He tells STOREYS one of the most important considerations to start involves how seniors enter and exit their homes, with the best case scenario being a garage or carport that connects to the home.

Booker says that the most common retrofits include everything from adding handrails, widening doorways, and installing universal flooring throughout the home, to equipping bathrooms with roll-in showers with benches, and kitchens with low-prep areas and shelves. To accommodate those with mobility devices, Chris Stigas, founder of accessibility consulting company HandiHelp, recommends appliances like fridges with either bottom freezers or vertical doors, and stackable washer/dryers that have buttons in the middle, as opposed to the top. Over-the-range microwaves will also need to be replaced with accessible countertop options, he says.

Larger-scale retrofits inevitably come with a hefty price tag. For example, a bathroom renovation to include the addition of a universal roll-in shower will cost $15,000-$20,000 – “on the low end,” says Booker. “If you’re looking for customization, then it will cost more than that.” Some may be eligible for help through initiatives like the Ontario Seniors Home Safety Tax Credit.

Some seniors – especially the more independent set – may find the simplicity and social aspects offered by an activity-packed seniors' lifestyle community attractive. Many of these communities have adapted with the times. “Today’s seniors prioritize active, purpose-driven lifestyles and seek options that offer a sense of community, and foster independence while providing personalized care,” says Ashley Sumler, Director of Quality of Life at Amica Senior Lifestyles, which offers luxurious seniors' residences. “There’s a growing emphasis on wellness, lifelong learning, and meaningful social connections. At Amica, we see this in the demand for enriching programs, curated experiences, and opportunities to explore new passions, whether through fitness, creative programming, or community engagement.”

Amica’s programming includes tailored fitness programs, chef-prepared meals, and amenities like theatres, outdoor spaces, art studios, and wellness centres – all aimed at enhancing residents’ daily experiences. “As we evolve, Amica will continue to incorporate biophilic design, immersive technology, and wellness-focused amenities,” says Sumler.

In 2021, seniors residence vacancy rates were on the rise in all provinces except for Newfoundland and Labrador, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). Currently, 7.9% of Canadian seniors live in residential care facilities like residences for seniors or healthcare and related facilities. According to the CMHC's Senior Housing Survey, the average cost for standard spaces (where the resident doesn’t receive high-level care, defined as over 1.5 hours per day) was $3075 in 2021.

Those with complex healthcare needs may be better supported in a LTC facility, says Thirgood. As C.D. Howe Associate Director of Research Rosalie Wyonch highlights in her recent study, there are 2076 LTC homes in Canada – many, with frustratingly long waitlists. Wyonch says those who require support and don’t have an in-home caregiver are significantly more likely to be admitted prematurely to LTC homes and about one in nine new LTC residents could potentially have been cared for at home or in a retirement home setting. The cost of a LTC home currently ranges from $5,400 to $1200 per month, on average.

It’s no secret that the onset of the pandemic in 2020 hit Ontario’s LTC homes hard, underscoring a glaring need for reform. Some LTC homes literally saw seniors die by the dozens from COVID-19 within days of one another, leading to widespread scrutiny, criticism, and – frankly – fear of the province’s LTC homes. “The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted long-standing issues in Canada’s LTC system – today, 96% of Canadians aged 65 years and older report that they will do everything they can to avoid moving into an LTC home,” says Thirgood. “Reform is needed to protect the physical and mental health of residents and to better support the wellbeing of care workers.”

Real Estate Market Impact

There’s been a widespread belief that aging Baby Boomers, who own 41% of all homes in Canada, would release an influx of housing onto the supply-strapped Canadian housing market. But that hasn’t exactly been the case – not yet, anyway.

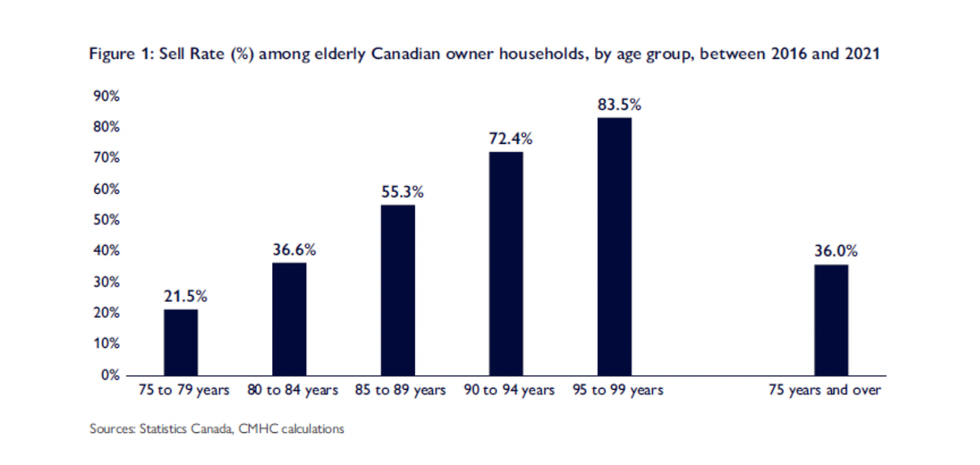

According to CMHC’s Housing Market Insight, the number of senior households who will sell their property is elevated only in relatively advanced age groups – something that reflects both the aging-in-place trend and longer lifespans. In fact, based on their data and calculations, Canadians wait until they’re in their 90s to give up their home. Therefore, CMHC says it will take another few years to see a “truly significant” number of senior households list their properties for sale. When they do, may some opt to downsize to condominiums, which could stimulate the struggling condo market with increased demand. As CMHC highlights, the proportion of condo-owning seniors increased by 5.1% between 2011 and 2021. In its November 2023 Housing Market Insight report, CMHC found that senior households in Vancouver and Toronto are most likely to opt for condos as they age. Montreal’s seniors, on the other hand, opt to rent.

Renting is becoming commonplace among Canada's seniors. According to new research from Point2Homes, Ontario’s fastest growing segment of the rental market are Boomers aged 65+. In the notoriously pricey Toronto, there are over 59,000 solo seniors who rent their homes. The report attributes factors like downsizing, the desire for less responsibility in those golden years, divorce, and widowhood as factors contributing to older Canadians as the more significant proportion of solo renters. If more seniors are choosing to rent, this will obviously place more pressure on the rental market, which has been historically dominated by young people, especially the smaller units. The Point2Homes study drives home the need to focus on creating adaptable homes that cater specifically to older renters and reduce financial barriers

"As the population ages, there’s growing demand for homes that feel supportive, welcoming, and adaptable to changing needs,” Alexandra Ciuntu, author of the Point2Homes study tells STOREYS. “For many, aging comfortably while maintaining independence is key, which could drive the residential market — especially rentals — toward housing options designed with accessibility, connection, and flexibility in mind. Technology might likely play a bigger role too, as a more tech-savvy generation ages and shapes demand for features like smart safety systems and tools to simplify daily living. Ultimately, senior living should aim to go hand-in-hand with the community — something Canada’s housing landscape is still trying to figure out."

The hard-hitting reality is that the number of seniors housing suites built in the past decade is simply not keeping pace with demand. Of course, current challenges exist when it comes to the cost to build any type of new housing project – seniors lifestyle community or not. These include everything from persistent red tape, to sky-high construction costs and development fees in regions like Toronto. In its latest Housing Market Outlook, CMHC projects that starts will slow down between this year and into 2027.

Meanwhile, a new research paper from the Real Estate Institute of Canada (REIC) highlights how senior housing is becoming a high-performing investment class. The lack of government funding for Canada's aging population presents a lucrative opportunity for private investors and developers to meet the rising demand for senior housing and long-term care facilities across the country, it argues. According to REIC, an additional 450,000 LTC and retirement home units are needed by 2040 to meet this demand.

How Can We Best Plan?

As Wyonch highlights, across Canada, more than $1 of every $4 of provincial government healthcare spending is directed to caring for people over 75. “Despite significant growth in total healthcare spending on seniors, per capita spending has declined in some provinces, showing that there is extremely limited fiscal capacity to increase spending per senior,” she writes. Wyonch points to shortcomings that exist in current policies that leave lower-income seniors and those who rent financially vulnerable to costs associated with retirement homes and care.

Wyonch shines the spotlight on an unmet need for home care in Canada, which invests fewer resources to home and community care than other OECD countries. Wyonch therefore recommends that provinces should invest in public home and community care, while also expanding private provision of care. Furthermore, they could take a page from Quebec’s book and provide a refundable tax credit for senior renters to access retirement home spaces and home-support services that enable seniors to age in place longer.

“Canada needs to reimagine where we live as we grow older and create more age-friendly communities,” says Thirgood. “A critical component of this will be ensuring that housing is accessible by adopting and enforcing accessibility standards and providing enhanced financial support for older adults who require modifications to remain at home. Mandating accessible design through building codes could greatly increase the supply of new housing that is accessible for all abilities – Canada’s federal housing advocate has recommended incorporating measures from the Accessible Dwellings Standard developed by CSA Group and Accessibility Standards Canada into legislation, making it legally enforceable to ensure compliance.”

CMHC suggests that some supply-side solutions include creating homes from existing units in the form of laneway homes or garden suites. While both were legalized in Toronto in 2018 and 2022, respectively, these types of dwellings have been disappointingly slow to gain traction. The REIC report highlights the potential to revive the struggling condo market by repurposing underperforming or unsold condos into senior housing, and points to examples of adaptive reuse of existing buildings, like Greenwood Retirement Communities' conversion of a 50-year-old Brampton Holiday Inn hotel into seniors' housing.

In a report released earlier this year, the National Institute on Ageing called on all levels of government to make the small care home model the standard across the country when it comes to the provision of long-term care. This marks a “transformative shift” away from delivering care in large institutional care settings to smaller, more personalized, shared home-like environments. Doing so is aligned with public preferences and intended to improve both care outcomes and working conditions.

“There are great examples of housing innovation in Canada, particularly within naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs) where older adults are clustered in specific buildings or neighbourhoods,” says Thirgood. “This can be leveraged to create programs that more effectively provide health and social services, develop and sustain communities, and combat loneliness and isolation among residents. While there have been many NORC pilots and programs since the1980s, Canada’s policy environment has made it challenging to help scale these beyond the local and grassroots level. In this regard, we can learn from New York – the only jurisdiction in North America to recognize NORCs in legislation, set out a framework and funding eligibility criteria, and successfully expand.”

Thirgood acknowledges that planning for an aging population goes beyond the physical home. “Ensuring that physical and virtual environments are barrier-free will help lay the foundation for healthy aging,” says Thirgood. “For example, an accessible public transit system with robust specialized para-transit services will enable older adults to engage with their community and maintain social ties, and incorporating the perspectives of older adults in the design and development of new technologies and services will ensure equitable access.”