From Rolex, Tiffany & Co., and Van Cleef & Arpels, to new Chanel, Dior, and Gucci stores, Toronto’s Yorkdale Shopping Centre houses the world’s top luxury brands under one ever-evolving roof. It’s sleek, chic, and curated – a different world than the Yorkdale I knew growing up. And the now-luxury mall’s message is becoming loud and clear: Unless you’re one of us, you can’t sit with us. In a court ruling on February 9, Justice Jessica Kimmel blocked Fairweather-owned brand Les Ailes de la Mode from moving into Yorkdale’s former Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) real estate.

According to court filings, Oxford Properties, Yorkdale’s landlord, said Fairweather stores “look and feel temporary and downmarket.” So, Oxford would rather lose millions in rent than cheapen the Yorkdale brand, which they call a “leading luxury retail destination.” Harsh? Maybe. But when we consider the future of Yorkdale, and of the shopping mall in general, the “mean girl” move makes sense.

Yorkdale’s Luxurious Glow-Up

Back in the pre-social media days, Yorkdale Shopping Centre was pretty comparable to other Greater Toronto Area (GTA) malls. It featured live animals at PJ’s Pet Centre, a variety of mid-market clothing stores, and a generic food court with the usual fast food options. Luxury items were essentially limited to the designer-filled Holt Renfrew, a Yorkdale tenant since the mall opened in 1964. Another original tenant? Fairweather. The women’s brand remained a Yorkdale staple until its lease expired in 2020.

While you can still find mass-market retailers – brands like American Eagle Outfitters, Dynamite, H&M, and Zara, for example – Yorkdale’s overall vibe has become one of high-end luxury. This is reflected in shiny new and upcoming mall arrivals, which include an 11,000-sq.-ft Yves Saint Laurent flagship, the first Canadian Tom Ford flagship, and a 12,000-sq.-ft Gucci global concept store, set to unveil this year.

According to Craig Patterson, founder and publisher of Retail Insider and a leading retail analyst, Yordale’s luxury transformation began with the 2009 arrival of Tiffany & Co. “Then, around 2013/2014, Bulgari, Cartier, and Ferragamo opened,” says Patterson. “I’d say about 12 years ago is when Yorkdale really just started accelerating as a luxury mall."

Yorkdale has been in a perpetual state of evolution since. The 2012 arrival of a new food court signalled a shift toward more premium dining, while the 2016-2018 East Expansion converted the former Sears location into a massive lifestyle wing housing Restoration Hardware, Sporting Life, and The Cheesecake Factory. In 2023, Oxford Properties Group announced another renovation for the mall – this one with a $28-million-dollar price tag – that would become home to Yorkdale’s recent luxury tenants and their impeccably designed retail spaces.

Yorkdale’s long-term vision is one of mixed-use, and includes the addition of nineteen residential towers on its property. This means the mall will become a front yard to thousands of new residents – an undoubtedly important consideration as we question what will fill the mall's HBC-shaped void.

The “Better Empty” Argument

Essentially, Oxford is avoiding the cheap fix to protect its long-term asset, even if it means losing millions in would-be rental income. First, a bit of context: As the landlord, Oxford owns the space, but RioCan owns the rights to the space, holding the long-term lease for the former Hudson’s Bay Company space – and it wants to fill it.

In January 2026, RioCan and court-appointed receiver FTI Consulting argued that Fairweather’s “Ailes” concept was a “commercially sound” attempt to stabilize a distressed asset. In court filings, they argued that the department store was a higher-end concept featuring brands like DKNY and Steve Madden, aligning with the head lease's requirements. For RioCan, which was funding a $75-million loan on the vacant space, the deal was a necessary hedge against a dark anchor that produced zero revenue while accumulating millions in interest.

According to 2026 court filings, Fairweather proposed paying just $1 million annually for the 300,000-sq.-ft space – a huge drop from the cool $2.8 million previously paid by HBC. But, for Oxford, the real risk wasn’t the low rent; it was asset dilution. Oxford Vice President Nadia Corrado testified that locking in a “downmarket” tenant for a 50-year lease — which could be extended further, to the year 2142 — would cost hundreds of millions in lost prestige, eventually devaluing high rents paid by surrounding luxury brands. So, for Oxford, a brand like Fairweather is a multi-decade liability.

To a casual observer, turning down $1 million in annual rent seems like financial self-sabotage. But as commercial retail analyst Ross Moore explains, Oxford is playing a much more sophisticated long-game. While a property’s value is a function of Net Operating Income (NOI), Moore notes that in the short term, "the value will fall, but with the prospect of replacing a low-rent department store with retailers possibly paying more, the cap rate may even fall, giving a small boost to net asset value (NAV)." Calling Yorkdale Oxford’s “crown jewel,” Moore cites it as a special case where brand integrity outweighs immediate cash flow.

“It is better for the landlord to wait for the right tenant(s) to enhance their target market's shopping experience vs. fill the space quickly with the wrong tenant,” agrees Bruce Winder, a retail analyst, and author of RETAIL Before, During & After COVID-19. “Having said that, they do need to fill the space as it becomes an eye sore after a while and they lose traffic and revenue.”

Realistically, it’s not like Yorkdale is struggling. With $2 billion in sales annually, it’s currently Canada’s most successful mall. “It’s critical for Oxford to maintain and grow Yorkdale's premium positioning in order to preserve their position in the market and their business model,” says Winder. “Premium shoppers make up a disproportional amount of spending right now and Oxford needs to ensure they remain a destination for this segment.”

The Ruby Liu Precedent

While their move may give pretentious vibes, Oxford’s rejection of Fairweather is backed by Canadian case law. Patterson points to a legal test established in the high-profile 2025 Ruby Liu (Central Walk) vs. HBC case. Canadian billionaire Ruby Liu was blocked from taking over 25 former HBC leases when Justice Peter Osborne ruled that a landlord can reject a lease agreement based on the "appropriateness" of the tenant and their track record in managing a massive retail undertaking.

“The judge must decide whether the proposed business is a suitable fit for the shopping centre in a specific anchor space,” explains Patterson. So, for a mall that’s spent the last 15 years meticulously curating a loop of luxury, the Fairweather brand isn’t just a style clash – it’s a legal liability.

In the world of Canadian commercial real estate law, both the Ruby Liu and Fairweather cases have fundamentally shifted power back into the hands of the landlord. It also marks the end of an era where any paying tenant was a good tenant. Instead, Yorkdale’s selectivity is part of a strategic, multi-million-dollar plan.

Archaic Anchor Stores?

From the looks of things, the traditional anchor store is on its way out. The beloved HBC is just the most recent casualty in Canada’s mall department store demise. Some malls have not filled the space Nordstrom, which made its anticipated Canadian arrival in 2016, left behind in 2023. Let’s not forget about Sears (2017) and Target (2015) before that (RIP).

As much as I love a good department store, these massive spaces are now tricky to fill with one brand. So, malls are subdividing. At CF Toronto Eaton Centre, the former Nordstrom space has recently become a Simons, a Nike flagship store, and an Eataly. According to a 2026 report from JLL, 64% of vacant HBC space is currently being subdivided into mid-size boxes. Meanwhile, 22% is planned for redevelopment and just 14% will be allocated to a single tenant.

“Department stores just don’t have the same drawing power they did back in the 1950s, 60s, 70s and 80s,” says Moore. “The model has long since broken down, and now regional mall owners need to look to a more diverse range of retailers that can perform the same function, and maybe even pay a bit more rent. The biggest challenge is taking very large floorplates and demising this space into blocks that work in terms of layout and functionality. No doubt some very creative architects will come up with something that will work, but it’s not an inexpensive option.”

Indeed, Canadian malls are reinventing themselves, moving away from self-defining through traditional anchor stores in favour of mixed-use and luxury-focused strategies. Given Yorkdale’s move to residential towers, perhaps making the real estate more of a lifestyle hub than a shopping centre makes sense. Premium-paying future residents would likely rather have an Eataly or Equinox downstairs than a Fairweather.

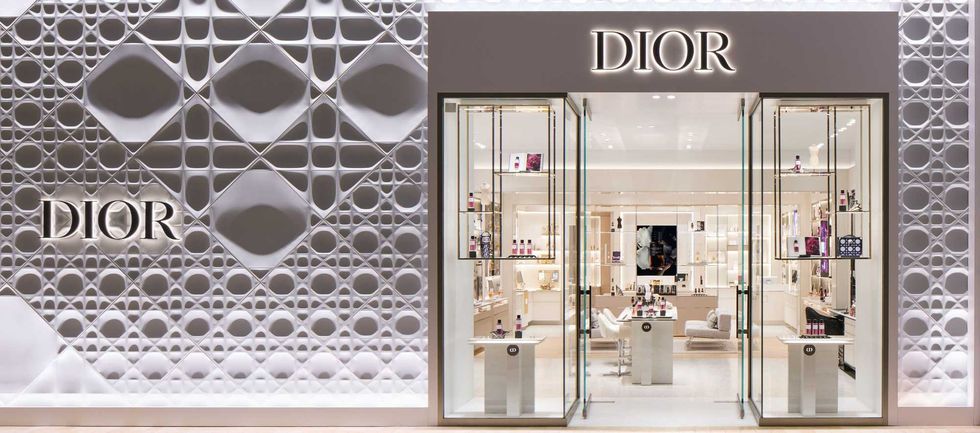

Essentially, the Yorkdale mall brand itself is becoming more of a draw than its anchor stores. Yorkdale no longer needs large anchor stores to draw traffic – not when there are micro-anchors like a Dior store complete with a 145-foot-long, 3D “Lady Dior” quilted handbag facade, or a Louis Vuitton with a two-storey LED screen that animates the Monogram flower motif.

Brand image and lifestyle considerations aside, the math makes sense at Yorkdale. Consider the numbers. To a landlord, one Chanel, where the average entry price of a handbag is around $10,000, is better than a dozen mid-market anchors. According to Patterson’s reporting, Yorkdale’s Chanel location is projected to generate $100 million annually – roughly double the sales volume of Chanel’s standalone store on Yorkville Avenue. It’s also nearly 12(!) times the total revenue Fairweather’s proposed concept would likely produce — in a space 30 times the size.

Life in the Dead Zone: The “K-Shaped” Economy

In the luxury market, the in-person shopping experience is as important as the actual purchase. Buyers want to feel the caviar leather of a new Chanel bag as they weigh their options in their hands, or try sparkly diamond Cartier jewellery on for size before swiping the credit card. In 2025, physical luxury stores accounted for 81% of all personal luxury goods sales globally. Tellingly, the same year, luxury retail square footage in North America actually rose by 65%, even as general mall foot traffic declined.

The same success isn’t necessarily true for mid-market brands. In the wake of the pandemic and with the mass rise of ecommerce, we’re seeing challenges for the middle class mall. Retail analyst Bruce Winder says that middle class retail is disappearing, while luxury and discount brands are thriving. Winder refers to this as a “K-shaped” economy – and it's a starkly divided one.

For affluent Canadians on the upward trajectory of the “K,” wealth is anchored in appreciating assets rather than stagnant wages, allowing them to treat high-end luxury – AKA a trip to Yorkdale mall – as a form of investment. Meanwhile, on the downward path, today’s economy has forced most consumers to trade down to discount banners to manage rising costs. This leaves middle-market retailers like Fairweather in the dead zone of the “K.”

“We all know that middle retail has been the hardest hit over the last decade,” says Winder. “Luxury is doing well, value is thriving, but the middle is suffering as the K-shaped economy continues its importance. Retail is unforgiving and newer generations may see other brands as more relevant also.”

Some strategic suburban malls that can’t attract luxury brands are putting their real estate to use for things like entertainment centres, grocery stores, and fitness centres. For example, the former HBC location at Oakville Place has been entirely reimagined as a Nations Experience, a 120,00-sq. ft hybrid of a massive multicultural grocery store and a high-tech amusement park.

Of course, this would be off-brand for Yorkdale. "That box at Yorkdale is quite prominent; it’s 15% of the square footage of the entire mall,” says Patterson. “It’s a significant piece of space that is going to have a visual impact on the shopping centre, especially given its visibility from highways. Perception, to many, is the reality.”

Beyond the Box

If the middle is a dead zone, Yorkdale isn't exclusive for the sake of it. It’s future-proofing itself. You can still be a thriving mid-market mall in global cities if you’re a tourism and transit hub like Eaton Centre, where sheer volume is your greatest asset. Or, perhaps, if you morph into a multi-service hub like Thornhill’s Promenade Shopping Centre. But those are different stories.

For Yorkdale, it appears the power move for 2026 and beyond is the showstopping standalone flagship – the type that are anchors for the mall in their own right. These micro-anchors create a destination that is immune to the department store rot, offering an exclusivity that can’t be replicated.

Let’s not forget about the mall’s thousands of new neighbours. For them, Yorkdale isn’t just a nice place to shop, it’s a priority amenity. As Moore suggests, the traditional department store box is a "relic of a bygone era,” and the mall’s retail mix could very well dictate the success of the upcoming residential buildings. By choosing a dark anchor – at least, for the time being – over the wrong one, Oxford is essentially revealing that in 2026, the most expensive thing isn’t an empty space. It’s a diluted brand.