Canada’s much buzzed about and, at times, controversial mortgage stress test is up for review.

On December 15, the federal government will decide on potential adjustments to the mortgage stress test’s minimum qualifying rate (MQR) on December 15.

In a report released yesterday, RBC Assistant Chief economist Robert Hogue says policymakers are likely going to err on the side of caution and leave the substantial two percentage-point buffer in place. This is despite the current climate of sky-high interest rates that we haven’t seen in years.

“Now that interest rates have surged to their highest levels in more than a decade, the odds of a further spike in the period ahead have greatly diminished,” writes Hogue. “This will (or should) be an important consideration when Ottawa decides on potential adjustments to the mortgage stress test’s minimum qualifying rate (MQR) on December 15. Whether there will be any changes made to the size of the MQR’s hefty buffer is another matter.”

Hogue says he suspects policymakers will want to maintain a high degree of stringency in order to contain borrower or systemic risks in still highly uncertain times.

The mortgage stress test has been a hot button issue since its current form was first rolled out back in 2018, highlights Hogue. “Federally regulated lenders must ensure borrowers are able to withstand a sharp increase in interest rates by using a markedly inflated qualifying rate (the highest of 5.25% or the contract rate plus two percentage points),” writes Hogue. “This rate has frustrated potential home buyers with less than stellar borrowing credentials -- some of whom are no longer able to get a mortgage from federally-regulated lenders (at least temporarily). It’s also impacted stronger borrowers by reducing the maximum size of mortgage they qualify for.”

Hogue says that the stress test fulfilled its main purpose; protecting against a rate shock. According to Hogue, when interest rates were at historic lows, it made perfect sense to test borrowers against a massive increase.

“Indeed, the low rates meant there was a high probability of an increase over the term of the mortgage (five years is the most common in Canada),” writes Hogue. “The events of the past year are a case in point. The Bank of Canada’s policy rate increase has been sudden and massive (up 350 basis points in just eight months). The subsequent shock now confronting borrowers is exactly what the test was designed to protect against. It has enhanced both their resilience and that of Canada’s financial system.”

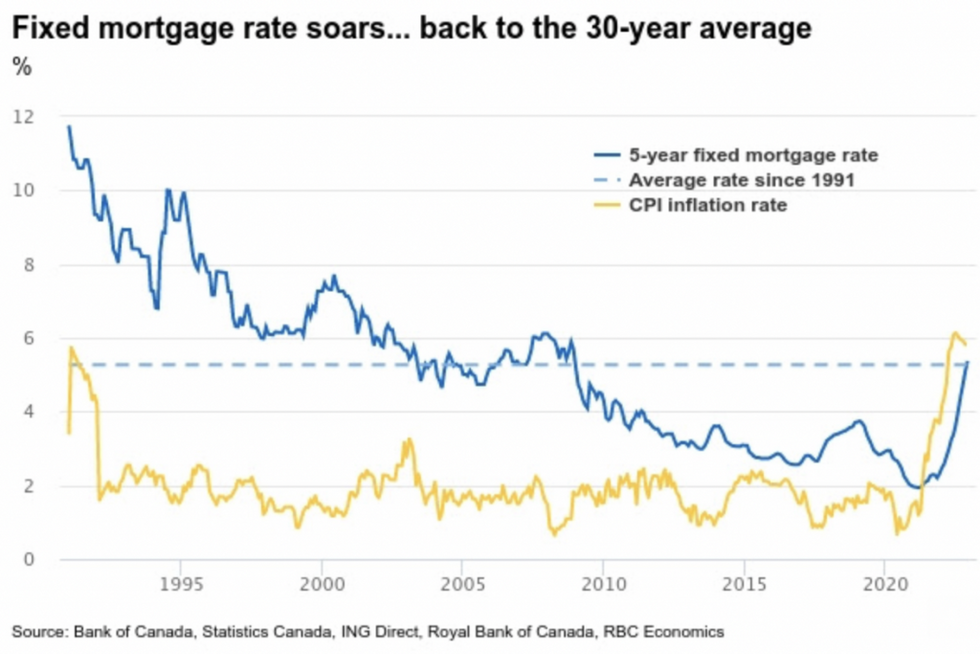

With that said, Hogue questions whether what was optimal a year ago is still the case now, with today’s much higher interest rates. “The likelihood they will rise by another 200 basis points is slim,” says Hogue. “Since the Bank of Canada adopted its inflation targeting policy in 1991, the five-year fixed mortgage rate has been above the current qualifying rate (around 7.7%) only 16% of the time. By comparison, when the stress test was implemented in January 2018, the qualifying rate at the time (around 5.3%) had been exceeded 50% of the time in the prior quarter of a century. Clearly the stringency of the test has significantly increased.”

As Hogue highlights, however, the stress test isn’t just about interest rates.

“It’s also intended to guard against other potential shocks like a drop in borrower’s income (e.g. due to a job loss) or developments (e.g. soaring cost of living, recession) that could threaten one’s ability to service a mortgage,” writes Hogue. “As we contend with four decade-high inflation and with our economy teetering on the brink of recession, such risks are evidently elevated.”

While the stress test may ruffle some feathers, Hogue says that getting rid of the stress test completely would not be advisable, nor is it even under consideration. “The test is an important prudential policy tool that is proving its worth in the face of soaring rates,” he writes.

So, while there is certainly a valid case to deduce the MQR buffer, Hogue believes policymakers will leave it in place as is. “We also suspect they would be weary of any moves that might ultimately stimulate housing demand at this stage -- or go against the Bank of Canada’s efforts to cool our economy down to tame inflation."