If renowned modernist painter Gordon Smith hadn’t lived to 101 years of age, it’s highly probable that his Arthur Erickson designed house — probably the most famous Erickson residence in the country — wouldn’t have survived.

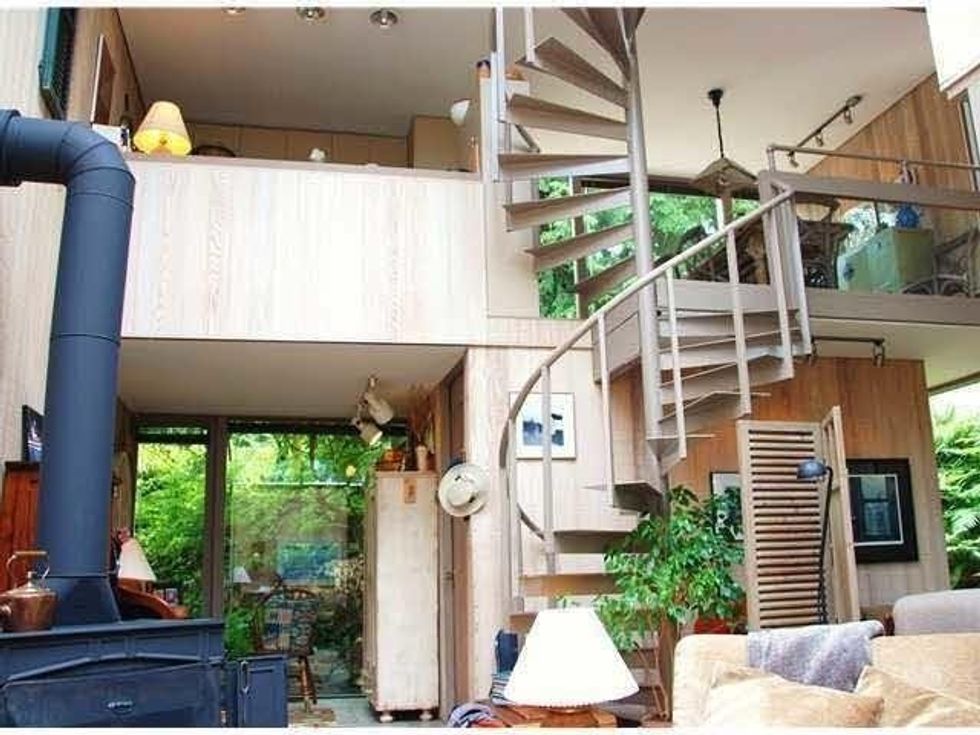

The small house, built in 1964, with extensive glazing and cantilevered beams, sits nestled within a forest setting near the ocean in West Vancouver, on a lot worth millions. Considering the land value, a lot of buyers would have knocked the house down, cleared the trees and built a mansion. But Smith, who commissioned Erickson to build the house for him and his artist wife Marion, who died in 2009, lived in the house until his death in 2020. The couple didn’t have children, and Smith wisely left the house in the hands of Equinox Galleries owner Andy Sylvester and curator Daina Augaitis, who’ve spent the last two years restoring it.

As a fundraising drive for the Arthur Erickson Foundation, they are showing off the results with group tours on June 24. It is the first public viewing of the famous modernist house, which includes a new display of contemporary art on the walls (Smith donated much of his own stellar collection when he was alive). The $500 ticket also includes an optional tour of artist-writer Douglas Coupland’s house nearby, hosted by Coupland himself. (Coupland was a dear friend of Smith’s).

And tickets are being snapped up — which tells you something about the level of interest in Erickson’s work. It tells you something else, too, says heritage expert and consultant Don Luxton.

“It tells you something about marketing,” he says. “The Smith House is the greatest house that Erickson did, arguably, and the fact it’s preserved is a triumph. You never keep everything, but it shows that it’s possible to find the right owners for these buildings. And that that house had an audience.”

Not all midcentury modern houses are so lucky. Back in the 1950s and 1960s architects who favoured modern designs had free rein on Vancouver’s North Shore, particularly in West Vancouver, with its ocean views and rugged forested slopes. Land was relatively cheap and the geography a welcome challenge to the new generation of designers who were keen on integrating the lush surroundings. They built a lot of modern houses with a particular West Coast style.

But with land now at a premium, and real estate investment a key market driver, it’s difficult to justify a small house on a large lot, says Luxton. That makes marketing of the houses key to their survival — especially without crucial government policies in place to save them, including incentives, such as tax breaks for those owners that do preserve them, he says.

“Nobody is trying to help these [home owners], so the fact that any of these buildings survive is remarkable,” he says. “The hope for them is you’ve got to increase the value of the building in terms of how you market them, and you have to make it a prestige thing. That works in other jurisdictions, in Palm Springs especially. People are mad to buy these midcentury modern houses, especially if a star lived there. But it’s a different market in Palm Springs.

“So there is a lot that’s working against the buildings in Vancouver, and mainly it’s just sheer land value.”

The latest Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver statistics show that despite interest rates doubling, home prices have increased about 5% year to date. Near record-low inventory has created a competitive price environment despite the increased cost of borrowing, according to the board. Buyers are looking, which puts pressure on vulnerable West Coast Modern homes that are relatively small in relation to their lot size.

That’s the problem for the house designed and lived in by architect Robert Hassell, at 5791 Telegraph Trail, in West Vancouver, which is listed for $1.99M. The tall cedar-clad structure called Hassell House is being marketed as a teardown with no regard for its provenance. On the other hand, there is also the Bowker House, a Fred Hollingsworth and Barry Downs collaboration that is on the market for the first time in more than 50 years that is being marketed for its midcentury prestige and splendor, with 20-foot-high cathedral ceilings, exposed wood expanse and considerable glazing and views of Howe Sound. The 2,794-sq.-ft house, built on a large lot at 6850 Hycroft Rd. in West Vancouver, is listed for $3.198M.

Luxton says it’s difficult to tell what percentage of the houses have been lost and how many have been saved because so many are undocumented.

West Vancouver has identified 124 houses built between 1945 and 1975 as having architectural importance. Only six are municipally designated heritage buildings from that time period. But their preservation depends on the property owners who appreciate them, and little else.

Maintenance of the homes is up to the owner, and if a house falls into disrepair there’s little that can protect it, says Luxton.

“It’s hard to say what percentage are disappearing but certainly there is an erosion of the building stock, and except for some prominent buildings, not everything is going to be saved.

“At least [realtor] Trent Rodney and some others are trying to market these things. At least there is more awareness.”

Rodney made a splash last summer when his firm sold a 2,434-sq.-ft Erickson house on Eagleridge Drive, known by architects as Catton House and re-named Starship House by Rodney because of its angular shape. That house sold for $4.3M and made it clear that West Coast Modern houses have an audience that is willing to shell out. Critics complained about the re-naming of significant homes for marketing purposes, but Luxton says the names don’t matter as much as the fact that the houses are surviving.

Rodney is currently marketing another Erickson house, this one in the seven-acre Monteverdi Estates that Erickson designed beginning in 1979. The community consists of 20 homes, most of them on a hillside, with landscaping by legendary landscape architect Cornelia Oberlander. But house No. 8 is on a flat lot, and it’s the first time it’s been on the market in a decade, according to Rodney.

“A lot of people think it is a strata community because of the extra community space, but it’s not,” says Rodney.

Not one house in Montiverdi Estates has been torn down. And Rodney — who has carved out a successful niche selling the general West Coast Modern style — says he hasn’t sold a house that got demolished yet. Instead, he has buyers, mostly creative types, patiently waiting for exceptional examples of midcentury or West Coast Modern houses to come up for sale. His strategy is that he prices the houses for their value, not just the cost of the land.

“The reason we haven’t had one demolition is we charge a premium for the architecture as a work of art. So when we market a piece of architecture, people understand there is a premium attached to the building and the architectural significance there.”

Luxton took the same approach years ago as founding director of Heritage Vancouver. By telling the story behind a house, he says they gave the building cachet. Suddenly people would want to own a home by Samuel Maclure, a West Coast architect from a much earlier period.

Again, it comes back to the marketing.

“You have to see them as having a pedigree, like collecting fine old cars,” says Luxton. “It’s a prestige thing. Erickson houses are being bought by people who treasure them. They have real value to people. But those are the exceptions.

“Your average run-of-the-mill midcentury modern building might not hit that level.”

As the market heats up, those houses will just become demo bait.