There are many historic buildings in Toronto with important ties to LGBTQ+ history. The phrase “meet me under the clock,” was an invite to the St. Charles Tavern just north of College Street on Yonge Street. The tavern, whose fire house clock tower was being incorporated into a condominium (that project has since entered receivership), was a popular drag spot, but also the site of violence against the community.

The Brunswick House was where four lesbian women dubbed “The Brunswick Four,” were refused service and dragged out by police after performing a parody of the song I Enjoy Being a Girl, which they adapted to I Enjoy Being a Dyke in 1974. The women inspired the LGBTQ+ community at time when activism was growing.

There are also a series of homes scattered throughout Toronto’s east and west end, sitting on quiet residential tree-lined streets, on top of businesses along major roadways or steps away from the hustle and bustle of the city.

The homes unsuspectingly play a part in the story of a gay activist who dared to change how the community was perceived and gave Canadians a perspective of the lifestyle at a time when many hid their sexuality. These homes were once the residence of Jim Egan, a man many consider Canada’s first gay activist.

The Life of a Pioneering Activist

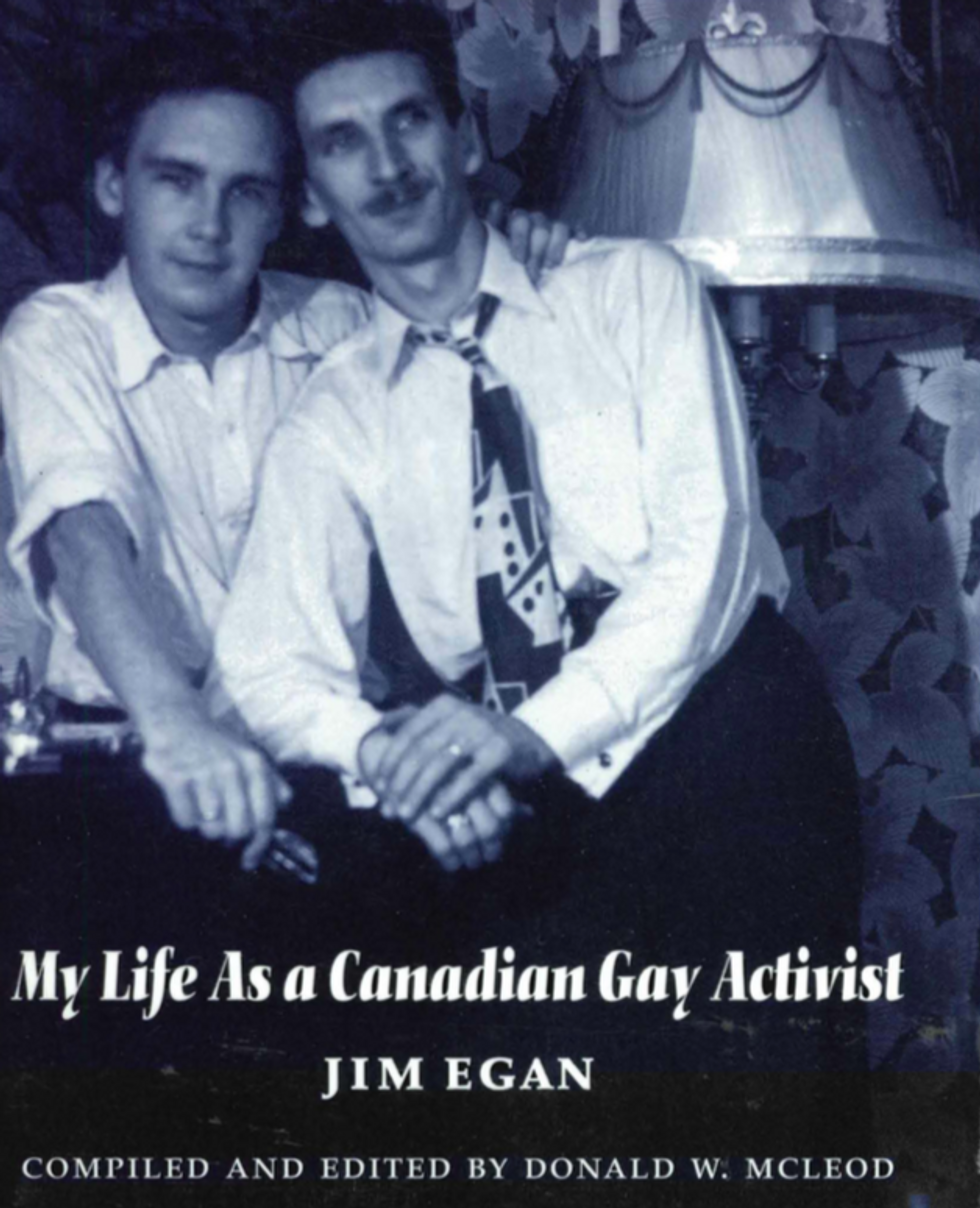

James Leo Egan was born at St. Michael’s Hospital on September 14, 1921 and died on September 3, 2000 in Courtenay, British Columbia. The eldest son of James Egan and Nellie Engle, he attended Holy Name School and Eastern High School of Commerce. In his book, My Life as a Canadian Gay Activist, Egan reveals it was at age 13 or 14 when he realized he was sexually attracted to males.

He tried to enlist during WWII but was rejected due to a corneal scar. He went to work at the University of Toronto in its Zoology Department, embalming rabbits and preserving frogs, and later at Connaught Laboratories in their insulin production department. He eventually joined the Navy and stayed until 1947.

READ: Legendary Houses: An Apartment for Dance Pioneer Celia Franca

After experiencing gay culture in Europe, Egan began immersing and learning about Toronto's gay scene. One establishment, the Savarin Hotel on Bay Street, is where Egan met his life partner Jack Nesbit. Within a few weeks, they moved in together at Cotswold Court Apartments on Cumberland Street. They moved multiple times in their life to Oak Ridges and Beamsville in Ontario and British Columbia. It was in Oak Ridges when Egan began challenging a culture of homophobia presented by the press.

Fighting Back One Letter at a Time

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, headlines and stories in local tabloids were homophobic, villainizing the gay community with depictions of its members being abnormal and sexual deviants. There was even a publication that felt “pervert” was an appropriate synonym for homosexual.

It was a dangerous time to come out, leaving many of these inaccurate depictions unchallenged. Egan decided to change that and began writing letters to editors whenever he saw one of these headlines. He wrote to local tabloids like Flash and Justice Weekly and American publications like Esquire and Parents Magazine.

It took time for his first letter to be published, but Egan worked hard to debunk and protest these misconceptions and provide an honest depiction of homosexuality. He was offered a column in the tabloid True News Times titled “Aspects of Homosexuality” and a series for Justice Weekly titled “Homosexual Concepts.” He’d also help Maclean’s Sidney Katz on his piece “The Homosexual Next Door: A Sober Appraisal of a New Social Phenomenon.”

His partner Nesbit was uneasy with his activism. When Egan started being noticed in Beamsville for his letters, the pair relocated to Toronto. They separated for a period, but eventually reunited and moved to British Columbia. Egan would write letters on and off for 15 years until 1964.

Egan helped drive change again after his partner was denied spousal allowance benefits under the Old Age Security Act because same-sex spouses were not eligible. The pair appealed the decision and took it to the Supreme Court of Canada. While they lost, the Supreme Court of Canada agreed that equality rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms should encompass sexual orientation -- a major win for the LGBTQ+ community.

Mapping Egan’s Residential History

Egan’s memoir maps out his living situation from birth. There are four homes Egan identifies that still stand in Toronto, and one undisclosed home in the College Street and Spadina Avenue area and Cotswold Court Apartments which was demolished.

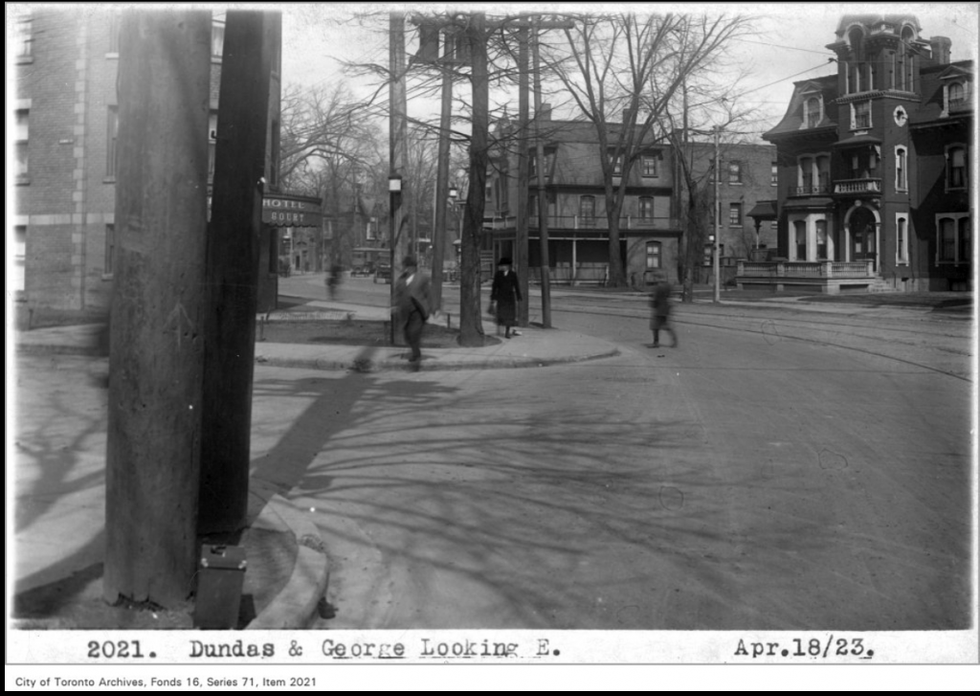

The residence at 281½ George Street located a few doors north of Filmores Hotel, then the Wilton Court Private Hotel, was where Egan lived in his infancy. Today, it is a rooming house, gated off with a sign on the front door reading “George House.” The main and second floor have decorative semicircle stained glass windows sitting above unimpressive modern windows. The main floor window and entranceway both have archways and the second floor features a balcony.

Toronto’s Danforth Village neighbourhood also has an Egan family residence at 39 Westlake Avenue. The semidetached home is well over 100 years old. It has beautiful columns struggling to hold up the veranda’s caving roof, uneven front stairs and discoloured bricks on the facade. Egan notes he has only vague memories of his time on Westlake Avenue as a child other than the nearby Danforth Creamery.

The home at 245 Bain Avenue, another childhood residence, sits on a quiet street in the Riverdale neighbourhood by Withrow Park. The house has a sunroom in the front, not original, but the home itself has a flat exterior with a second-floor window popping out.

In 1963, Egan and Nesbit rented an apartment above the Bloor Supermarket at 1052A Bloor Street West in Bloorcourt Village. The building, according to a dirt ridden building marker, was built in 1922. Today, the apartment sits above The Maker Bean Café and its façade has been stuccoed. The unit Egan lived in was described in his memoir and notes, “...one of the bedrooms there has been converted into a library study, and the walls were lined with bookcases.”

Pride

As I searched the streets of Toronto for Egan’s former homes and told his story to community members and current homeowners, they were honest in that they didn’t know who he was. Egan’s legacy may not be as obvious as some whose names are on plaques and buildings, but his story, bravery, and trailblazing actions resonate throughout the LGBTQ+ community fuelling pride.

Three years ago, a Heritage Minute about Egan’s life was released. It was the first LGBTQ+ story of the over 75 shorts made. As we celebrate Pride Month it’s important to remember Egan’s story, the other influential people who led change, the events that prompted their causes, and the work we still need to do.

(Lead image of 281 ½ George Street in 2021)