It's not the answers that matter, it's the questions. For city builders — whether they are politicians, planners, developers, architects or engineers — asking the right questions is the most crucial component of the process.

Inability to understand this leads inevitably to failure.

Talking to a room full of professional urbanists earlier this month, DIALOG principal, Antonio Gomez-Palacio, was blunt about the problem.

"In truth," he told those assembled, "we as an industry don't know what we're talking about."

The purpose of the gathering was to discuss a handbook that will address city-building through the lens of community well-being.

The report, which will be published in July, was prepared by DIALOG, a multi-discipline design practice, and the Conference Board of Canada. It will be available in July, free of charge, to all interested professionals.

"It's not an abstract conversation," Gomez-Palacio explains.

"It's about a series of issues that can be dealt with in concrete ways. We're trying to shed a light on social well-being. We need to ask ourselves whether we're creating environments where people are welcome."

That sounds obvious, but looking around the built environment of Toronto and its surroundings, it's clearly a lesson we have yet to learn.

"We don't think that planning and architecture can solve all the problems in the world," says another DIALOG principal, Craig Applegath.

"But what we do has a direct impact on people's lives. We still have to plan for the future even though we don't know what it will be."

Perhaps the best-documented connection between built form and people's lives, Applegath argues, is planning and active lifestyles.

The obesity epidemic that has swept across North America, for example, is due in part to the drastic reduction of walking in modern life. In the name of the car, vast swaths of suburbia have been laid out for the convenience of drivers. As a result, even for those suburbanites who would be pedestrians, there are few places to walk.

As Applegath also points out, "One of the big challenges of suburban neighbourhoods is loneliness."

This isn't something Canadian governments talk about. It is revealing, though, that last January, Britain's hard-right Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May named a minister for loneliness.

UK statistics tell us that nine million Britons describe themselves as lonely.

Clearly, architects, planners and developers play a role in dealing with such an intractable problem. Single-use zoning, for instance, can leave seniors isolated, not just in apartment towers but in neighbourhoods that have nothing to offer but more of the same.

But who's raising issues such as these?

The developers don't. Their concern is to sell units. Neither do architects. Their worry is design. Nor do planners. Their preoccupation is the rulebook. That leaves politicians, who spend their capital playing to the crowd with measures like keeping taxes low and filling potholes.

The Community Wellbeing Framework provides these same professionals with a list of specific questions that enables them and their clients to see beyond the myopia of their training, experience and ambition.

The document suggests, for example, that builders should try to determine whether the people who live in their subdivisions feel "welcomed, safe, and engaged, 24/7, regardless of background or physical ability."

They might also want to know if residents "have access to support facilities and services — daily, and during moments of need."

Other questions the DIALOG/Conference Board team identified are:

Does the project facilitate the uptake of active transportation, active lifestyles, and reduced car-dependency?

Can people of different income levels afford a high quality of life?

Can people realize the activities of everyday life within walking distance?

Are a diversity of perspectives, stakeholders, community, and disciplines meaningfully integrated from the outset and throughout the implementation/life of the project?

These are just a few examples, each indicative of an exercise carefully crafted to clarify thinking and open eyes.

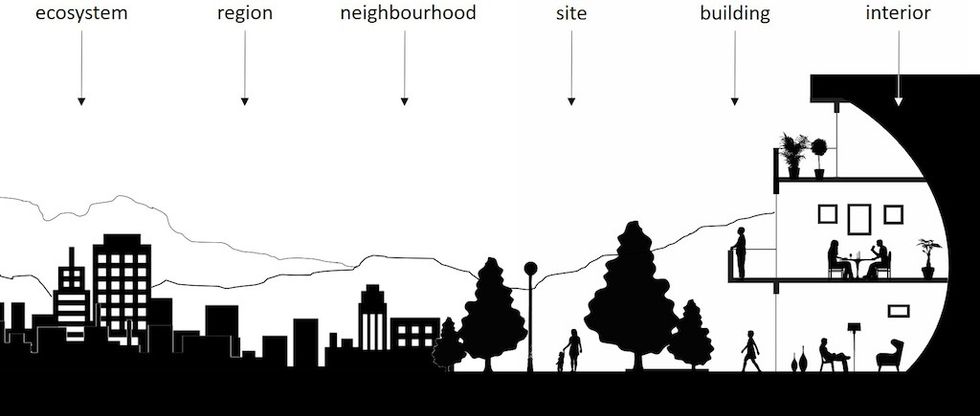

This attempt to create a more holistic approach to city building is a sign of Toronto's growing maturity and a deeper understanding of the need to see each project within the larger civic context. No longer is it enough simply to examine and judge a proposal in terms of how it meets an existing set of largely arbitrary criteria.

What will make the document important is whether it marks the beginning of a cultural shift.

Rules and regulations will change, of course, but that won't alter how professionals think. To accomplish that will be infinitely more difficult, especially in a city where political leadership has become an obstacle to change.

But as the handbook also shows, with the civic government missing in action, leadership now comes from the other sectors — institutional, professional and private.