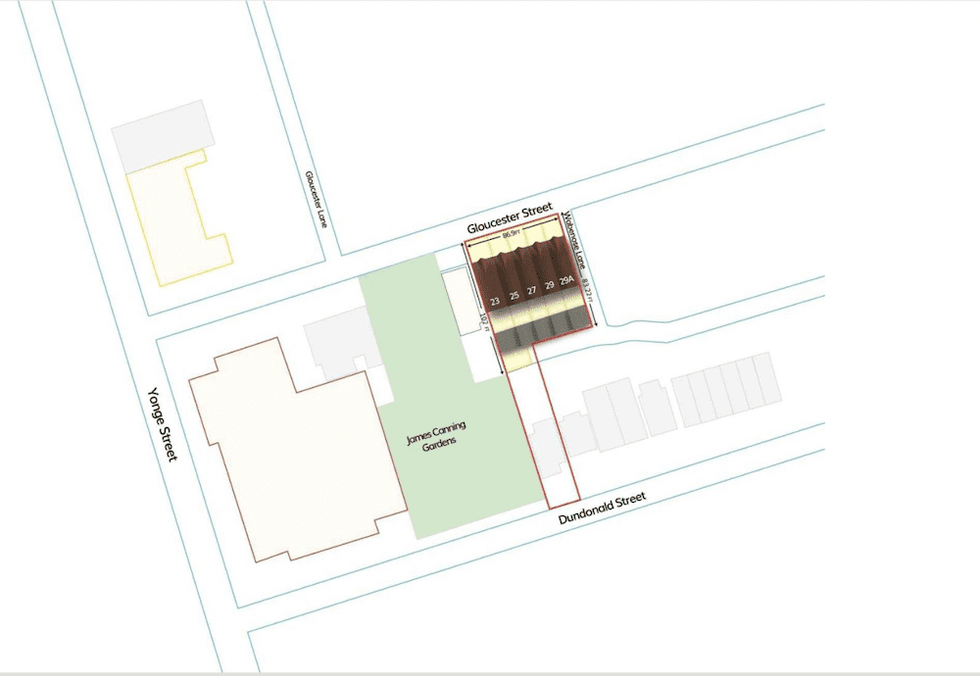

An air of frustration hangs about a strip of properties nestled on a quiet street in the vibrant Church-Wellesley neighbourhood. The stately brown brick townhouses running between 23-29a Gloucester St. -- along with 16 Dundonald St., located one block south -- are part of a consolidated parcel for sale, listed at $49,230,000.

However, attempts to sell the lots, which have been underway since January 2021, have faced several hurdles -- and owners are now concerned current efforts are being quashed again with what they call the weaponization of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

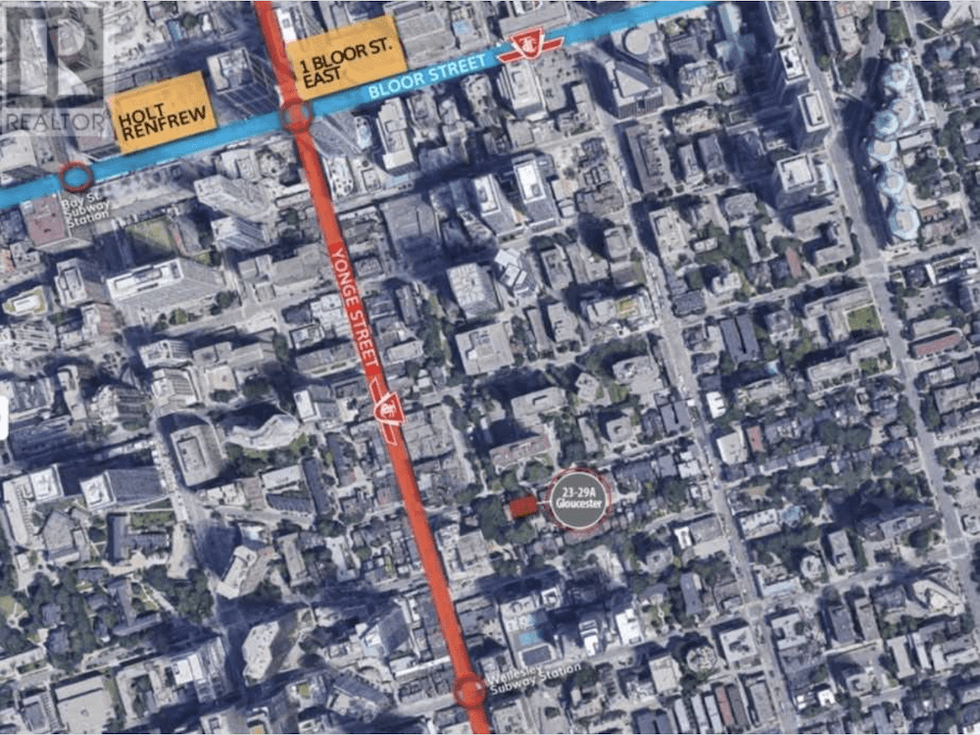

The properties in question are located just east of Yonge St., with 16 Dundonald positioned directly across from the Wellesley TTC subway station. The surrounding neighbourhood has seen rapid intensification; a total of 19 active development applications are currently underway in the direct vicinity, including the new Concord development Gloucestor on Yonge going up just steps away.

However, this particular patch of street differs from the rest of the neighbourhood in that it lies within the Gloucestor / Dundonald Character Area, one of nine designated protected neighbourhoods outlined by the North Downtown Yonge Official Plan Amendment, (Official Plan Amendment 183). That means any new development must conform to stringent design directions. Notably, OPA 183 stipulates that “large scale and tall building developments are not appropriate built forms for this Character Area.” It also states that while most of the buildings within the CA are not listed within the City of Toronto Heritage Inventory, “a large number of them carry notable and distinct architectural design.”

In order for a tall tower to be erected on the Gloucestor lots -- and with a price tag of $49M, it’s clear the sellers intend to attract a developer for that purpose -- a Zoning By Law Amendment (ZBA) and Official Plan Amendment (OPA) would be required.

Neighbourhood Pushback

But that it’s at all possible a tall tower could be built there has drawn the ire of the Church-Wellesley Neighbourhood Association (CWNA), which wrote in a recent newsletter, “The Gloucester / Dundonald Character Area is unique in its aim of strongly protecting low-rise dwellings, because it is surrounded by other Character Areas that allow for higher density.

READ: Can Toronto’s Heritage Study Stand Up to NIMBY Attitudes?

“If the properties were sold to a developer, a proposal for a tall building would be opposed by the City and by CWNA. If the developer appealed the proposal to the Ontario Lands Tribunal and succeeded in having the Neighbourhood zoning thrown out in order to erect a tall building, the precedent would essentially green light the Manhattanization of our neighbourhood's quieter side streets, both east and west of Church Street.”

A spokesperson for the CWNA, who requested to remain anonymous given his personal connection to involved parties, told STOREYS that the sellers and their representation are “dreaming in technicolour”.

He says that unlike other towers that have been recently erected in the area -- each of which the CWNA has “gone to the mat” for and reviewed closely -- a build on this particular strip falls outside of the context of OPA 183. “This is why a ZBA is going to be rejected by planning, because it’s inconsistent, and then it would go to the OLT [Ontario Land Tribunal], he says. “And, while the OLT is in favour of developers more than the OMB was, nevertheless, this is a very defensible situation.”

“The Horse Has Left the Barn”

Claims such a build would cause the “Manhattanization” of the community seem ironic to Graham Alloway, Broker of Record and lawyer at Catalyst Real Estate Brokerage Ltd., which is representing a number of the sellers in the consolidation.

“I think the expression is, ‘the horse has left the barn,’” he says, pointing to the multitude of towers recently erected south of Bloor. “Zoning would obviously have to be changed, but the precedence for the amendment to the zoning are already there, starting with the Concord development, which is literally sitting right next door to this particular development, and the one that is to the south side on Dundonald. So the precedent for the amendment to the zoning is everywhere.”

“Everybody is entitled to their opinion, but nobody ever wants what is going on in their backyard.”

“We Barely See the Sun Anymore”

That the neighbourhood is insistent on preserving this particular spot is baffling to Steve Martin, one of the consolidation’s sellers; he points out that their patch of Gloucester remains the only untouched strip, as towers abound in all directions. That they’re not able to cash out seems nonsensical, he says, given the city’s overall mandate to increase intensification, and the fact they’re located so close to the subway line.

“What we’ve noticed in the last 13 years living on the street is that everything around us is becoming towers and yet the south side of Gloucester and the north side of Dundonald are restricted -- and now we’re feeling like we’re living in the valley of the towers,” he says.

“We barely see the sun anymore, our gardens are suffering, it’s just not a very good quality of life. We just don’t understand why the City would insist [against a development] when you’ve got around 11 neighbours, all willing to consolidate, to give maybe 400 new families the ability to live downtown, with subway access, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from having to travel from the suburbs to their jobs downtown. All this put together, to us, just does not make any sense.”

A longtime resident of the Church-Wellesley neighbourhood who’s invested in the community over decades -- even raising thousands for the CWNA Foundation -- Martin says he feels personally slighted.

“When you have a community that doesn’t want to see change for the sake of their own good -- what about your neighbours that have greatly invested in this community all along? This is part of our retirement plan: I just turned 60. To be picked on because it’s zoned as residential but everything else around you is not, the way I look at it is when you’re in a major city, and it’s a growing major city, anything within a block to two blocks [of] a subway line should never be restricted to low-density housing. It just doesn’t make sense.”

The Question of Heritage Status

But zoning rules aren’t the only bump a prospective purchaser would face -- there’s also the issue of 16 Dundonald. Known as the Francis William Johnston House, it was built in 1907 and was home to one of the area’s first alderman and his wife, Maria Island Johnston. It’s considered to be an example of Edwardian Classical-style architecture and features the neighbourhood’s only crenelated bay window, says Adam Wynne, the local volunteer historian who recently nominated the property for heritage status.

While a heritage designation wouldn’t prevent redevelopment outright, it would require a developer to include particular elements of the property in its planning.

“Ideally it would be more than just the facade, because we do see a lot of ‘facadectomies’ as we call it in Toronto,” Wynne says. “But from my understanding, the community does not want to see a large tower on this site.”

However, Martin says it’s a stretch to say the unassuming red-brick home -- which was last sold in February 2009 for $690,000 -- has retained any actual heritage value, given the changes made to it over the years. “The property they mention for heritage -- if you live downtown and you go and look at that property, you’re going to say to yourself, ‘What are they talking about?’ That property was purchased probably about 10 years ago, they’ve completely remodeled the entire outside of that house,” he says. “There’s nothing heritage about it, but the community wants to use the heritage foundation as a weapon against any development whatsoever. I could understand, if it was an amazing house and kept as it was 150 years ago, OK. But in this case, it hasn’t been, so there’s nothing of heritage to be kept.”

It wouldn’t be the first time a sale for the parcel would be thwarted by technicalities. In fact, this is the second iteration of the consolidation. The first, which was active between January -- May 2021, did indeed draw an offer from a developer. That deal fell through, and Martin speculates it was due to resistance to the developer’s (who can’t be identified for legal reasons) entry into the neighbourhood, based on previous negative dealings with the city, along with confusion around the city’s impending Inclusionary Zoning bylaw.

He bases his theory on a conversation he had at the time with Ward 13 Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam, saying, “I know that when we had a meeting with her last year, when the offer from the developer was still on board, we said, ‘This developer is supposedly going to put in the 30% affordable housing.' And she at the time didn’t even seem to be aware of this new bylaw, and said, ‘I’ve never known this developer to put any affordable housing in any development they do.’”

“And then what we did find out later on after the deal fell apart was that this particular developer had another development that was supposed to go forward in the Yonge and Eglinton area, and the city councillor for that area had spoken to them and personally told him he was for the development. Then, when there was resistance from the neighbourhood, that same councillor was on the picket line with the neighbours. So apparently, this developer decided to sue the city. In that case, knowing that information, if I was in Wong-Tam’s shoes, knowing this particular developer that wants to go into her territory is known to the city, yeah, I wouldn’t want to deal with them either.”

Based on City of Toronto’s Inclusionary Zoning Bylaw, which went into effect in November 2021; the Gloucestor strip falls within IZM Area 1, which requires 10% of total new residential gross floor area secured for affordable ownership housing, or 7% for affordable rental.

“This is Not a Yonge Street Property”

However, Wong-Tam tells STOREYS that blocking such a development would fall well outside of her purview as local councillor. She says to her knowledge, no development permit has ever submitted to the city for the Gloucester lots, so it’s all very “hypothetical”.

READ: Toronto Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam to Seek Provincial NDP Nomination

“In no way have I said, ‘Don’t sell’ -- and it’s unlikely that I could dictate the price on an agreement of purchase and sale. I think that there’s a perception that the local councillor or a local representative can make things happen or stop things; I just don’t have those powers,” she says.

“But if they are looking for permissions from the city to change the zoning or permissions from the City to amend the official plan amendment, that is a highly disciplined process that is regulated through legislation. I think that’s where we need to begin -- if whoever wants to assemble this parcel, if they choose to do it, they can walk through the door and present their idea like hundreds of other developers that have done so in the City, throughout every ward. They come in and they say, ‘This is what we’d like to do, and this is what our proposals are.’ But no one has come forward to let us know what their proposals are, or what their intentions are.”

However, she adds, there are a “number of considerations” as to why the Gloucester site isn’t suitable for a tall tower, adding that it would have been long snapped up by one the city’s world class developers if that were the case. “Not every site in Toronto is a tall building site, and we have to be able to properly evaluate what sites should be tall buildings, and simply being close to a subway line doesn’t automatically give you the right to put in a tower,” she says. “This is not a Yonge Street property, the addresses are clearly on a side street, and there is no rationale for what I’d call a Yonge Street architectural typology. It’s not Bay Street where we’d expect very large and sizeable towers, it’s a side street, and a side street abutting a park and laneways.”

She also calls into question the parcel’s hefty price tag, saying it could be considered “disingenuous” to be marketed as an option for a developer in the first place.

“I think what I’m seeing is land speculators and potentially real estate companies knocking on a lot of doors in neighbourhoods offering very large amounts of money to property owners, telling them that they should sell, because they could reap tremendous profit if they can get a condominium built there,” she says.

“And I think there is a process here that is underway that I would say is disingenuous because those real estate brokers and those land speculators... they’re not the ones who are ultimately submitting the application for rezoning. They’ve made their commissions and they’ve made their money, and they’ve left. To get those applications through for rezoning, you’re going to have to work with a reputable developer who has assembled a team of experts who can guide them through a planning process.”