Around this time last year, something very interesting started to happen: developers across the country started to take aim at the development fees that governments levy on new construction and use to fund infrastructure projects. There has been varying levels of success, but what's undeniable is that there has been a sentiment shift around these fees.

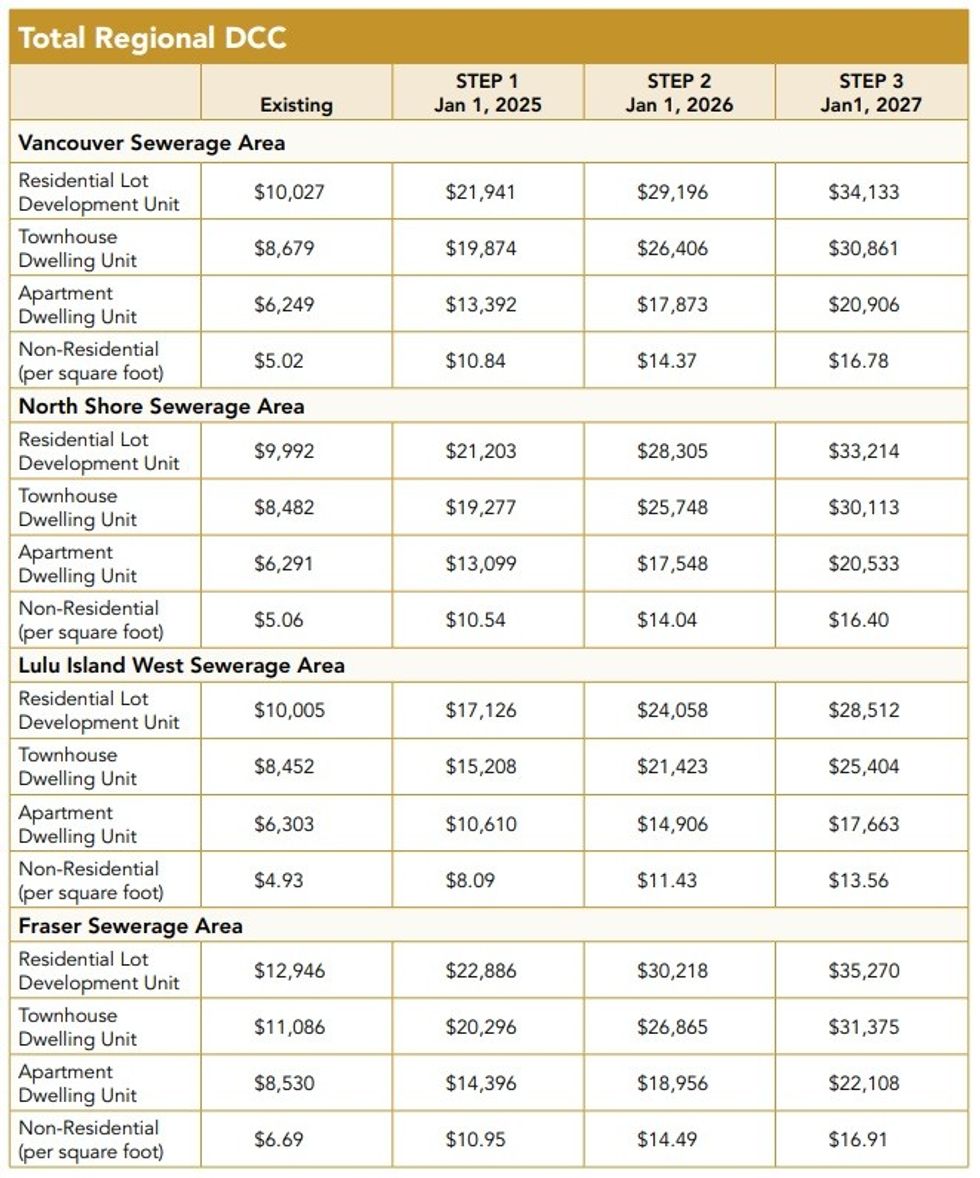

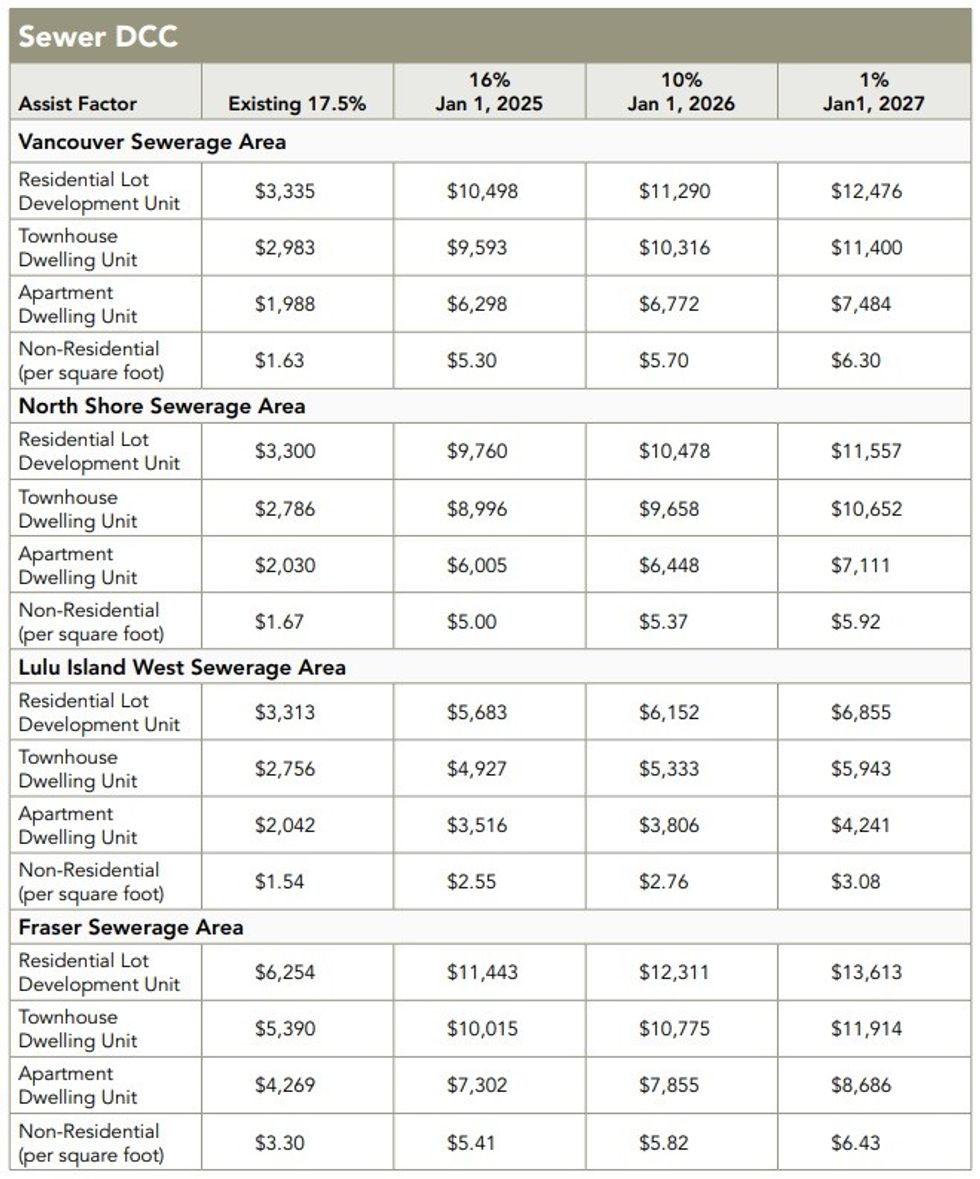

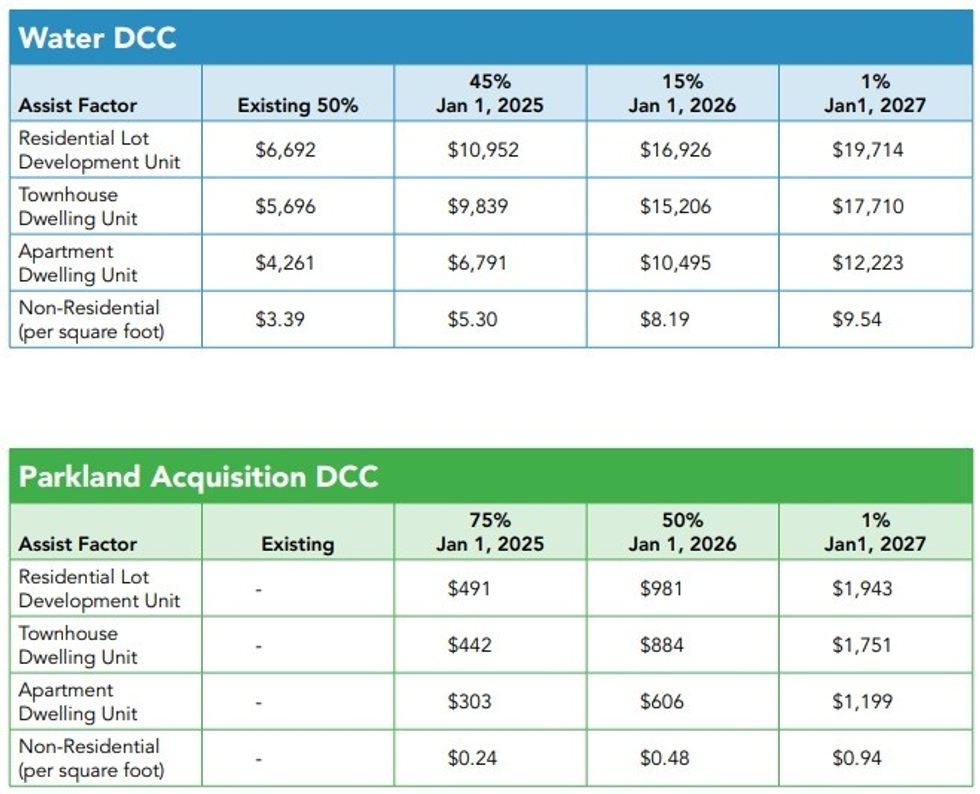

Here in British Columbia, the story really begins in Fall 2023, when the Metro Vancouver Regional District (MVRD) revealed that it was raising its development cost charges (DCCs) — in some cases doubling or triping the existing rates — which vary depending on location and property type. Despite pushback from federal Minister of Housing Sean Fraser at the time, the MVRD approved the increases, but agreed to implement the increases in phases on January 1 of 2025, 2026, and 2027.

After the increases were pushed through, all parties appeared to move on and the conversation died, until a group of prominent developers — Wesgroup, Polygon, and Anthem, among others — launched a letter-writing campaign in September, taking aim at the forthcoming increases. The developers were unified in asking for a series of changes, many of which have since come to fruition.

DCCs

Earlier this month, the Province announced legislative changes to allow 75% of DCCs to be paid upon occupancy or within four years, instead of paying it all upfront and within two years. Another change expanded the use of surety bonds for such payments, which developers often prefer to use instead of letters of credit. The Province also announced this month that it was extending the in-stream protection period for the MVRD's DCCs from one year to two years. On the local level, Vancouver approved a series of changes last month to also expand the use of surety bonds and to change the timing of when payments are collected.

Governments are showing a strong willingness to make these kind of changes and both Brad Jones, Chief Development Officer at Wesgroup Properties, and Rob Blackwell, Executive Vice President of Development at Anthem Properties, tell STOREYS that they have seen a sentiment shift around development fees over the past year — with some caveats.

Jones said he believes development charges started to get really bad around 2018. The City of Vancouver introduced Utility DCLs — DCCs are called development cost levies (DCLs) in Vancouver — in 2018, after the City realized it had a big infrastructure deficit, and the fees continued escalating from there before hitting a breaking point in 2022.

"That's when viability started breaking — in 2022," said Jones. "Revenues had gone up a lot — costs and revenue kind of move together and offset each other — and a lot of the sentiment among governments was that revenue was going up so we can up our fees and charges, but all that happened was viability eroded and we're seeing that now. I think we're going to see horrific housing start data when it flows through."

As for the changes governments have made recently, Jones grades them as "good, but not great." He points out that the change allowing 75% of DCCs to be paid upon occupancy or within four years doesn't come into effect until January 1, 2026, that the surety bonds change doesn't allow developers to replace existing letters of credit with surety bonds, and that the fee amounts are not changing like they are in other parts of the country.

Blackwell says all of the changes are welcome and "they all help to a degree," but points out that smaller developers may not be able to qualify for surety bonds and that the in-stream protection for Metro Vancouver DCCs, even after the extension, ends in March 2026, after which the rates jump up to the previously-planned 2026 rates.

"I think what you'll see is projects will just stop again, because they can't afford to pay those new rates," said Blackwell, who adds that the in-stream protection extension is only occurring because it was a condition of the $250 million in funding that Metro Vancouver is receiving via the Canada Housing Infrastructure Fund, as first reported by STOREYS.

CACs and ACCs

Another longstanding development fee in BC is community amenity contributions (CACs), which many local governments charge on new projects that require rezoning. These have historically been subject to negotiation between the local government and the developer, prompting the Province to create amenity cost charges (ACCs), which are intended to have set rates and replace CACs.

Although Burnaby and Coquitlam have introduced ACC programs, most local governments are still in the process of making the transition. Last month, however, Langley-based Lorval Developments won a lawsuit against the Township of Langley over its CAC policy. Surprisingly, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of Lorval and declared the Township's CACs policy as invalid and beyond its legal authority, calling into question all CAC policies in BC.

Lorval Developments Ltd. v. Township of Langley

In an interview with STOREYS earlier this month, Lorval Developments President & CEO Thomas Martini says they were planning a business park, film studio, and commercial space on about 70 acres of land that was designated for employment use. However, after the 2022 municipal elections brought in a new Council, the Township opted to update the Williams Neighbourhood Plan and introduce a CAC policy, resulting in Lorval being charged with nearly $40 million in CACs, which are not usually levied on commercial projects and made their project unviable.

Martini said there was no opportunity for discussion with the Mayor and Council, prompting Lorval to file its civil suit. Lorval is now reassessing the project and how to proceed. Martini says he believes that the ruling affects any CAC that any City has been charging and that the Province likely views the ruling as a positive because it encourages municipalities to transition to ACCs.

"What I think is important to highlight is that the Mayor and his slate took a gamble. When they ran in the last election, they were very clear that one of their main mandates was to have developers pay for soccer fields, and hockey rinks, and other amenities. I think that gamble hasn't paid off and I imagine they're quite embarrassed by that, because now they have to find the dollars to pay for the money they borrowed."

The Urban Development Institute says the implications of the ruling — which can still be appealed — could be significant and that they are reviewing the case. Both Jones and Blackwell say that the implications of the ruling remain to be seen, but could very well also become moot as local governments continue to phase out CACs and switch to ACCs.

"I think across the board, I've been surprised at how high the [ACC] rates are," said Jones, commenting on some of the ACC programs he has seen. "So far, the ones that have published projected rates have not really done a fulsome financial analysis, and I think that's a really important part of the process and legislation, because if you're doing those rates based on the market today, they're not viable. The municipalities are struggling to reconcile that because they all are trying to deliver amenities. But 100% of nothing is still nothing, so the rates need to be set in a way that we can deliver housing, because right now the cost of delivering new housing is more than the market will pay."

Will The Changes Make A Difference?

Both Jones and Blackwell say the changes that have occurred are positive, are welcome, and may help some projects, but are not enough to have a significant industry-wide impact that changes the market. Other costs such as those associated with land, financing, and construction have settled down recently, but the biggest cost remains development fees and none of the changes seen so far are going as far as to lower the actual amount of the fees.

"A fee that isn't viable still isn't viable whether you change the day of payment," said Jones. "The date of payment will help and it will help projects that are in-stream and trying to go ahead, but it isn't in a meaningful way changing the viability of projects. It's still a cost to the project and it's a really high cost. What you're doing is just moving the payment date and knocking the interest off. It's a meaningful amount of money, but it's not gonna take a project that's not viable and make it viable."

"Everything shifted and most project opportunities became non-viable when the Metro Vancouver DCCs went through," Jones added. "The theory is that it would reset the land market and land values would come down, but that's a misconstrued understanding because there's other things you can do with land. What's happening right now is sites — predominantly TOD sites — are worth more in their existing commercial retail uses than they are as a redevelopment, because of the fees and charges. We're having those conversations around the region right now where it makes more sense to leave a site as an existing strip mall or grocery-anchored shopping centre. That's a more financially-prudent decision, and higher land value, than it is to go undertake a multi-billion-dollar development. It's really undermining the provincial efforts around TOD."

For Blackwell, he says another aspect of the problem is the lack of coordination between different levels of government. As one example, he points out that Metro Vancouver pushed through the DCC increases in 2023 a month after the Government of Canada eliminated the GST on new rental construction. That kind of "one step forward, one step back" situation is still happening, he says, such as the Province's increased sustainability and adaptability requirements, which adds more costs than these tweaks save.

"I don't think anyone argues with the intent, because on its own, it makes sense, but you have to sort of balance it with everything else that is going on and be practical about it. It's not going to be one thing that's going to change everything, it's going to be an accumulation of different things that make a difference. For that reason, these changes are welcome, but to save money here and wipe it away by spending money in a different area, you're neutral and you're not making any progress."

"The in-stream protection helps those in-stream projects because they were underwritten with an understanding of what the rules are, and then the rules changed," he adds. "So you go back to what those rules are, and that helps make those projects perform as they were originally planned to perform, as opposed to under a new set of rules, but with new projects that are under a new cost regime, those are the projects that aren't moving forward."

The real problem, both Jones and Blackwell say, is the way infrastructure is funded, which is generally through the collection of development fees and property taxes. Because raising property taxes is tantamount to political suicide, the financial burden disproportionately falls on new construction. 'Growth pays for growth,' as many governments say. There is a glimmer of hope, however, as the Liberals pledged during the election to lower development fees and support infrastructure. When that comes to fruitition is unclear, but time is clearly of the essence.