In the spirit of the end of the school year and start of summer vacation, Desjardins opted to grade the Bank of Canada on its pandemic-era response -- and let’s just say the central bank didn’t make the honour roll.

The report, authored by Desjardins Managing Director and Head of Macro Strategy Royce Mendes and Associate of Macro Strategy Tiago Figueiredo, states that the Bank of Canada “deserves a passing grade” for its early pandemic strategy -- such as cutting its Overnight Lending Rate to 0.25% in a series of emergency cuts in March 2020, and introducing a number of asset buying programs to protect markets and credit systems.

READ: Canadian Economy Headed for a Recession in 2023: RBC

This helped the economy “avoid a much longer recession or even a depression,” the report states. However, they state, the BoC dropped the ball at the pandemic’s mid-point when it failed to launch its hiking cycle in a timely manner, and misjudged the tenacity of spiking inflation.

“Unfortunately, these programs were not scaled appropriately during the long middle of the pandemic and created market functioning issues,” the economists write. “In addition, restrictive forward guidance limited the Bank of Canada’s ability to respond to underlying economic conditions, delaying the removal of accommodation that would have been consistent with mandated inflation.”

“The Bank of Canada should perform an honest post-mortem on what went right and what went wrong.”

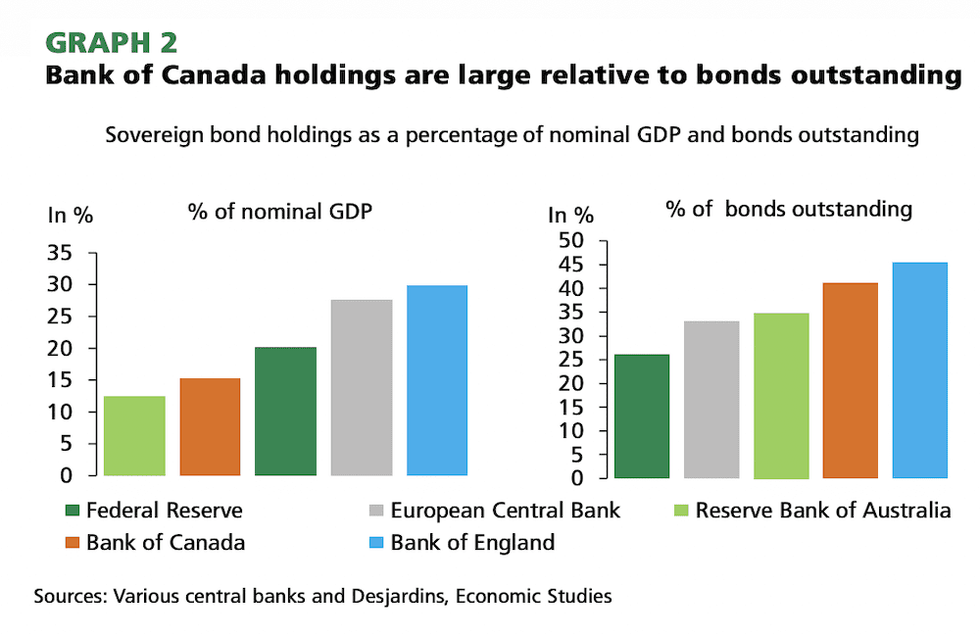

According to Desjardins, a key misstep for the monetary policymaker came with its Government Bond Purchase Program -- in order to keep the fixed cost of borrowing low, the Bank bought up to 60% of some bond issuings. It then held onto that massive balance sheet until April 13, when it announced it would kick off its quantitative tightening. That wasn’t soon enough, according to the economists; while the BoC’s bond holdings were low in comparison to some of its G7 counterparts, the size of its holdings “ballooned as a percentage of debt outstanding.”

“The Bank of Canada’s holdings relative to the size of the domestic bond market were clearly out of step with most other quantitative easing programs around the world,” write the economists. “And by the central bank’s own admission, that didn’t add much additional monetary stimulus. However, it did create market functioning issues, with the institution owning more than 60% of some bond issues.”

The Bank’s flunk out, though, was its refusal to hike interest rates at the first signs of stubborn inflation, insisting the trend was “transitory” in the early months of 2022. It didn’t embark on its rate tightening cycle until March, when it implemented a 0.25% increase. Since, it’s had to play catch up in its April and June announcements with supersized half-point hikes, and may need to deliver a 0.75-basis-point whammy next week -- a move not seen since 1979.

“The Bank of Canada also tied its hands with overly restrictive forward guidance. By committing to keep rates on hold until slack had been completely absorbed, it was acting like it was 2008 and the economy was suffering from weak demand,” the report states. “However, the pandemic took a major toll on both supply and demand and therefore required a different calibration for monetary stimulus.”

They add that the BoC’s insistence on using metrics such as the unemployment rate and capacity utilization rates didn’t account for disruptions restricting other forms of supply.

“As consumer prices began increasing more rapidly in 2021, the Bank of Canada’s pledge to keep rates on hold until “slack” was completely absorbed looked more and more out of touch.”