Take a look at the unit counts and suite mixes of new development projects and you'll typically see a good amount of studio units, a high amount of one-bedroom units, a similar amount of two-bedroom units, and then a significant drop-off in three-bedroom units.

Recently, Bosa Properties and Kingswood Properties revised their proposal for 1728 Alberni Street and 735 Bidwell Street in the West End of Vancouver, with the new proposal set to include a 44-storey rental tower with 20 studio units, 221 one-bedroom units, 136 two-bedroom units, and zero three-bedroom units, plus a 41-storey strata tower with a suite mix of zero studio units, 124 one-bedroom units, 83 two-bedroom units, and 29 three-bedroom units.

Similarly, for the McDonald's near Science World in Vancouver, Greystar recently proposed two towers that would provide a total of 371 rental units, with a suite mix of 73 studio units, 166 one-bedroom units, 114 two-bedroom units, and 18 three-bedroom units.

Over in Burnaby, Peterson and Create Properties have moved onto the first phase of their Burnaby Lake Village master plan, where Phase 1A will include a total of 116 studio units, 273 one-bedroom units, 228 two-bedroom units, and 22 three-bedroom units, while Phase 1B is then expected to include 72 studio units, 211 one-bedroom units, 204 two-bedroom units, and 18 three-bedroom units.

Those low totals for three-bedroom units stand out and there's a good reason: the profit margins on three-bedroom units are so low or non-existent that they are essentially subsidized by the smaller units.

The Numbers

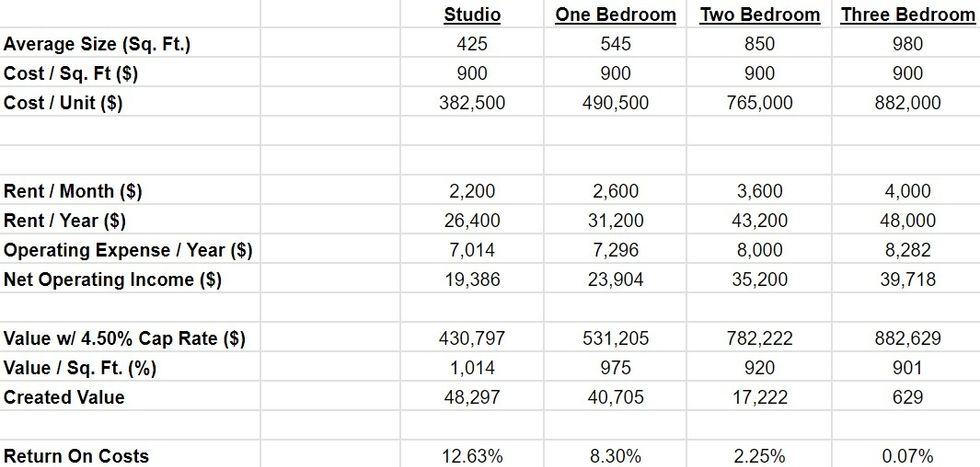

These days, factoring in all the various costs and assuming a relatively normal price for the land, the cost to build is around $900 per square foot, says Hani Lammam, Executive Vice President at Cressey Development Group, which is a flat number that doesn't change across unit sizes.

Based on average unit sizes of 425 sq. ft for studio units, 545 sq. ft for one-bedroom units, 850 sq. ft for two-bedroom units, and 980 sq. ft for three-bedroom units, the total cost translates to around $382,500 per studio unit, $490,500 per one-bedroom unit, $765,000 per two-bedroom unit, and $882,000 per three-bedroom unit.

Prior to announcing last month that it was delaying the change from March 2025 until 2027, the Province was also set to update the Building Code to require 100% of units in condo and apartment buildings to meet accessibility requirements, which many developers were very concerned about. The changes would have resulted in increases to unit sizes, increases in the size of non-leasible/saleable common areas, and less total units due to decreased efficiency, several developers have told STOREYS.

On the other side of the ledger is the income. For a rental building in an average location, asking rents of $2,200 a month for studio units, $2,600 for one-bedroom units, $3,600 for two-bedroom units, and $4,000 for three-bedroom units are realistically achievable (without factoring in affordability requirements). After deducting operation expenses, including property taxes, these units are held with an annual net operating income of around $19,386 per studio unit, $23,904 per one-bedroom unit, $35,200 per two-bedroom unit, and $39,718 per three-bedroom unit.

Assuming that income capitalizes at a rate of 4.50% — reasonable given recent interest rates, Lammam says — the yielded dollar value would be around $430,797 for studio units, $531,205 for one-bedroom units, $782,222 for two-bedroom units, and $882,629 for three-bedroom units.

Those numbers sound good and make the large units seem profitable, but after deducting the aforementioned costs per unit, which increase as the size increases, the net value created is $48,297 per studio unit, $40,705 per one-bedroom unit, $17,222 per two-bedroom unit, and just $629 per three-bedroom unit, which amount to returns on costs of 12.63%, 8.30%, 2.25%, and 0.07%, respectively.

The Cost-Benefit Analysis

"The real problem, though, is not that we don't make money off of the three-bedroom units, it's that we have to drive the revenue [higher] on the one-bedroom units in order to subsidize the three-bedroom units," Lammam explains. "It's not good enough not to make money on it. In order for me to be able to finance the project, I have to average out a return across all of it, so what really happens is the one-beds are subsidizing the three-beds. That's really what happens."

For strata units, the numbers are not much different, Lammam says, but the process is a bit different as developers have to pre-sell a certain amount of units before they can commence construction. It's commonly known that lenders generally require developers to sell somewhere between 60% and 70% of units in a project before they provide construction financing. However, what's less known is that they are often required to do so with a profit margin of about 15%, various developers have confirmed to STOREYS.

For developers, however, it's not as simple as just adjusting the unit counts to find the suite mix that works, financially, because many local governments have requirements around how many "family-sized units" — often defined as two-bedroom units and three-bedroom units — have to be provided. In Vancouver, for example, projects that involve rezoning are required to provide 25% of their units as two-bedroom units and 10% as three-bedroom units.

When it comes to the end users, whether it be buyers or renters, developers don't just look at what prices they can demand, they also have to look at the rest of the field and see what other options those end users have at that price-point. Yes, $4,000 a month for an apartment in Vancouver may be an achievable price, but that becomes less true if families have options to rent a townhouse in Surrey or Langley for around the same price.

"Once you get to a certain rent or purchase price, as a buyer, I have options," said Lammam. "The one-bedroom or even two-bedroom apartment appeals to that young, upstart new family, but the moment that family grows, it's hard to stay in an apartment, and I don't think it's the ideal. I don't think a family wishes they can live in an apartment, I think they wish they can live in a house."

Many of the families that end up in three-bedroom apartments are there because they can't afford a house, says Lammam, so there is no depth to the demand for family-sized apartments. Nonetheless, developers still have to meet the requirements.

"Are we trying to fit the square peg into the round hole? We're forcing developers to build three-bedroom units, but the market doesn't want it. It's not that they don't want three bedroom units, it's that that target market doesn't want the apartment format; they want a townhouse or a house. That's really the issue here."

Shrinking Margins

When developers undertake a project, they start with the ending: the returns they need to satisfy their lenders, investors, and themselves. They then factor in all of the parameters they have been given: the land cost, the amount of family-sized units they have to deliver, the DCCs, the construction costs, among others.

Those things are largely out of their control and essentially act as walls that are closing in on them from various directions, and the remaining space is what they have left to maneuver with.

Over the past few years, the requirements on returns have not been lowered. Meanwhile, the cost of land is still high, the amount of government fees continue to increase, and construction costs have also not dropped. On top of this, requirements pertaining to unit sizes, accessibility, and sustainability have stayed generally the same, been added, or increased, so the walls are just continuing to close in and the amount of space developers have to work with is just continuing to dwindle.

None of this is even factoring in the most important issue in our housing crisis: affordability. If the aforementioned rents are required to be set at CMHC median rents, or 20% below CMHC median rents, the achievable return on costs is then that much smaller, projects become that much less viable, developers become that much less willing to take them on, and our housing crisis, unfortunately, becomes that much more worse.

- Wesgroup SVP Of Development Brad Jones On The Challenges With DCCs, REDMA ›

- High Interest Rates Resulted In 30,000 Fewer Housing Starts In 2023: CMHC ›

- Inside The Metro Vancouver DCCs And The Potential Housing Price Increases ›

- Inside The Financing Challenges Developers Are Facing With Rental Projects ›

- How Long Does It Take New Market-Rate Housing To Become Affordable? ›

- A Breakdown Of Metro Vancouver's Housing Needs By Geography & Tenure ›

- Why Constuction Costs Are Higher In Vancouver Than Toronto ›