Although housing affordability in Canada is at its worst level in decades, sky-high home prices are actually keeping wealth inequality in check.

This is according to a new report from TD Economics, authored by Senior Vice President and Chief Economist, Beata Caranci, Managing Director and Senior Economist, Francis Fong, and Research Analyst, Mekdes Gebreselassie.

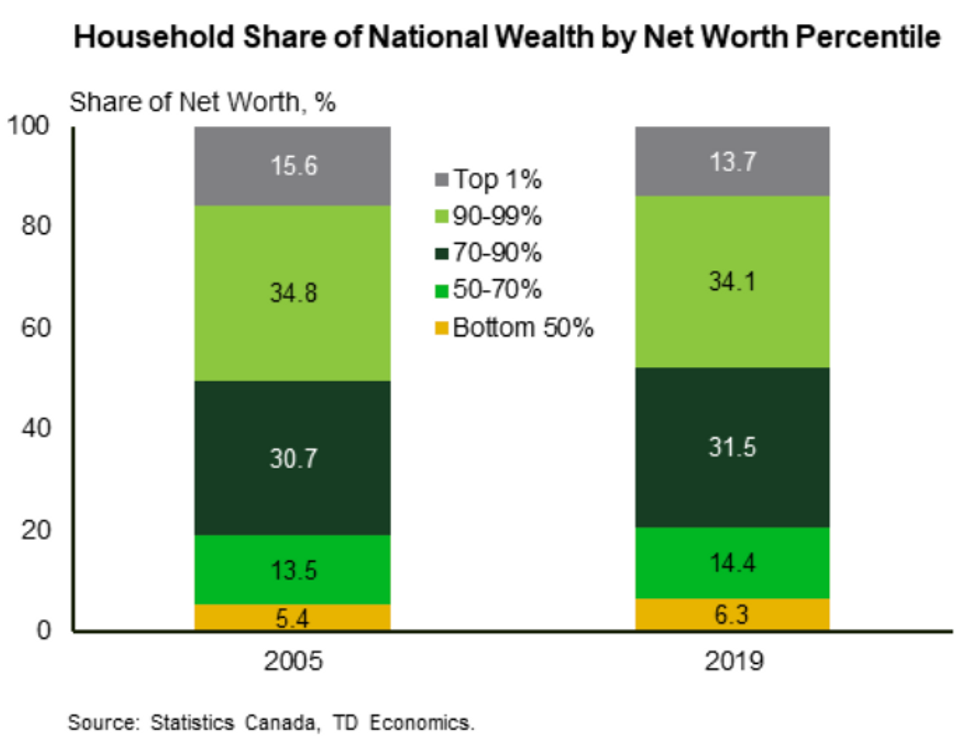

The report revealed that wealth inequality has narrowed in Canada. The share of wealth held by the top 1% and 10% of households declined between 2005 and 2019. Conversely, the net wealth of the lower percentiles has increased.

At the same time, housing prices are skyrocketing, with the national average currently 80% higher than the decade before.

So how are the two -- wealth inequality and housing affordability -- connected?

"Our goal was to disentangle to what degree deteriorating homeownership affordability has worsened or contributed to wealth inequality in Canada. We were surprised that the research showed wealth inequality has not increased in Canada, and that homeownership was one of the big reasons why," says Francis Fong in an interview.

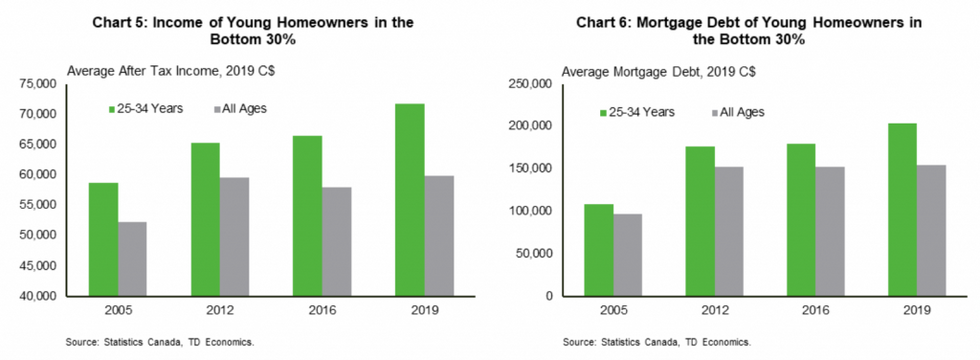

“Digging deeper into the data, we found that while homeownership rates among the younger age brackets -- particularly Millennials and Generation Z -- were similar to prior generations, they were more likely to have higher incomes and/or benefit from a transfer of wealth from parents and friends relative to the generations preceding them."

But while these young Canadians have high incomes and intergenerational wealth working in their favour, they’re also facing high-interest rates, inflation, and rising mortgage costs. Meanwhile, income levels have certainly not kept pace.

READ: "How High is This Sucker Going to Go?": Rising Rates Renew Calls to Tweak Stress Test

“For those with [financial] advantages, we found that debt levels are still higher than previous generations,” says Fong.

High debt levels are capturing young Canadians in the lower net worth brackets, but it’s that same group that’s responsible for pushing the bottom 30% net worth percentile up.

But TD cautions that, going forward, young Canadians are "likely to not just repeat, but accentuate the narrative of wealth inequality across housing lines with affordability now at its worst level in decades." Unaffordability will be exacerbated by rising interest rates.

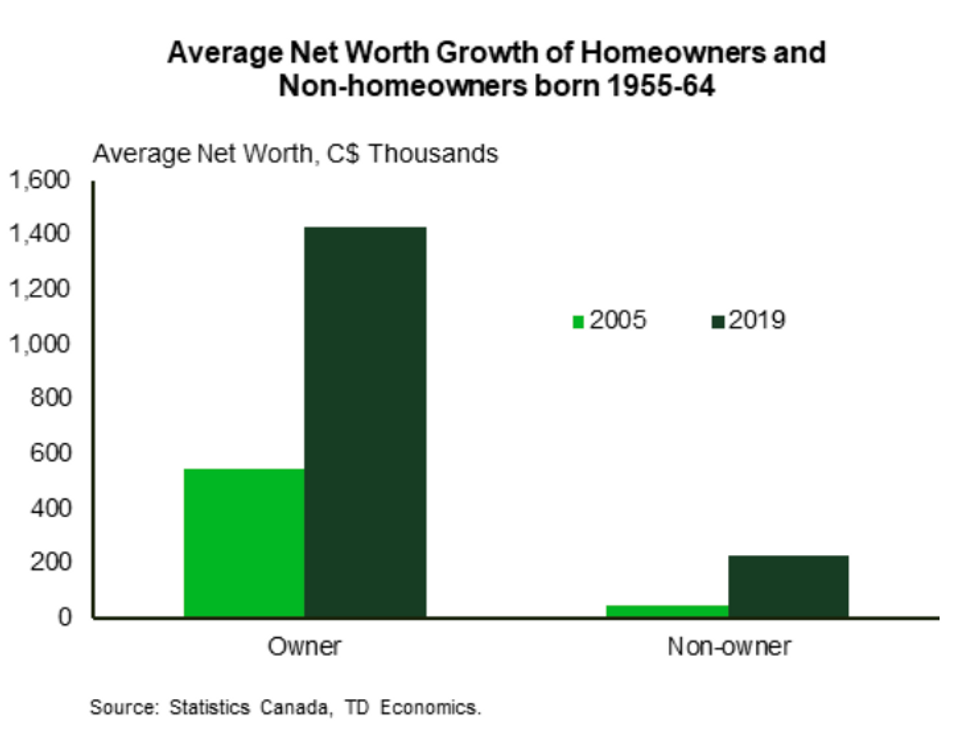

While real estate values are not currently driving wealth inequality, TD also found the wealth gap between homeowners and non-homeowners is indeed widening. The average net worth of homeowners born between 1955 and 1964 now exceeds $1.4M. This is more than six times that of their non-homeowner counterparts.

Fong explains that a big driver of the wealth divide is the fact that non-homeowners aren't able to reap the benefits of property equity or "forced savings."

“Housing is unique because it's the only non-financial fixed asset that appreciates over time, while you’re consuming it,” says Fong. “The homeowner simultaneously accumulates wealth as home prices rise because they are paying down their mortgage, and with each payment, their equity goes up. On top of that, there are many different subsidies and tax incentives that exclusively benefit homeowners and where there’s no directly comparable mechanism for people to build wealth who are non-homeowners.”

TD’s report goes on to say that specific policies need to be put in place to improve wealth outcomes for renters.

“This can be achieved either by re-assessing the current milieu of housing subsidies, or by providing targeted, equal-value supports for renters to allow the opportunity to save and keep up, rather than forcing Canadians to leverage to greater lengths in order to “get in.”

“On the surface, Canada might appear to be doing quite well on inequality, but digging beneath that surface shows that we have merely papered over the fissures that separate Canadians along housing lines. Governments should ensure they are assessing how new and existing policies can unintentionally deepen the divides and how to improve broader access to wealth creation.”