In cities that are facing a housing crisis, such as Vancouver, most people tend to agree that there is indeed a problem. The disagreement comes when discussing how to solve the problem, and that often boils down to a debate about density. Are high-density skyscrapers the way to go? Should that come at the expense of single-detached homes? Less discussed is what's in between those two options: missing middle housing.

But that's changing.

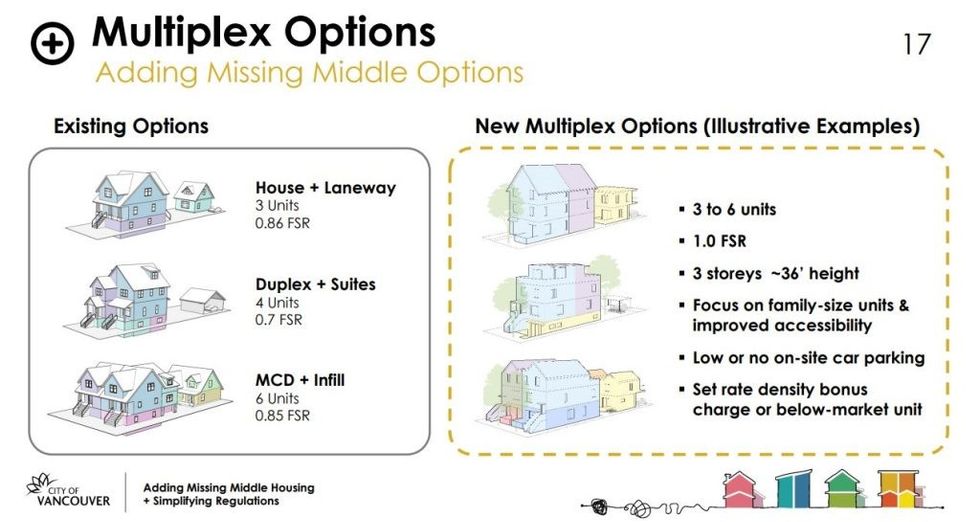

A term coined by the Founder of Opticos Design, Daniel Parolek, in 2010, missing middle housing consists of multi-unit residential buildings constructed in a house-size building, such as duplexes, multiplexes, townhouses, and low-rise apartment buildings. These types of housing were popular in the early 20th century, but eventually gave way to single-detached homes and then high-rises, and can fit seamlessly into existing residential neighbourhoods while providing a diverse array of housing options.

The City of Vancouver is currently in the beginning stages of a potential plan to add more missing middle housing, a process that began in January 2022 with a motion called "Making Home: Housing For All Of Us" that was moved by then-Mayor Kennedy Stewart.

"Vancouver suffers from a 'missing middle' of housing choices with the Downtown core featuring a highly-densified urban landscape but the vast majority of the remaining residential land reserved for legacy housing forms such as single-detached homes or duplexes usually too expensive for all but the wealthiest to rent or buy," Stewart wrote.

Last month, City staff returned with a presentation of their findings and how to add more missing middle housing. It's a step in the right direction, but many believe that the proposal, as currently outlined, doesn't go far enough to make a significant impact.

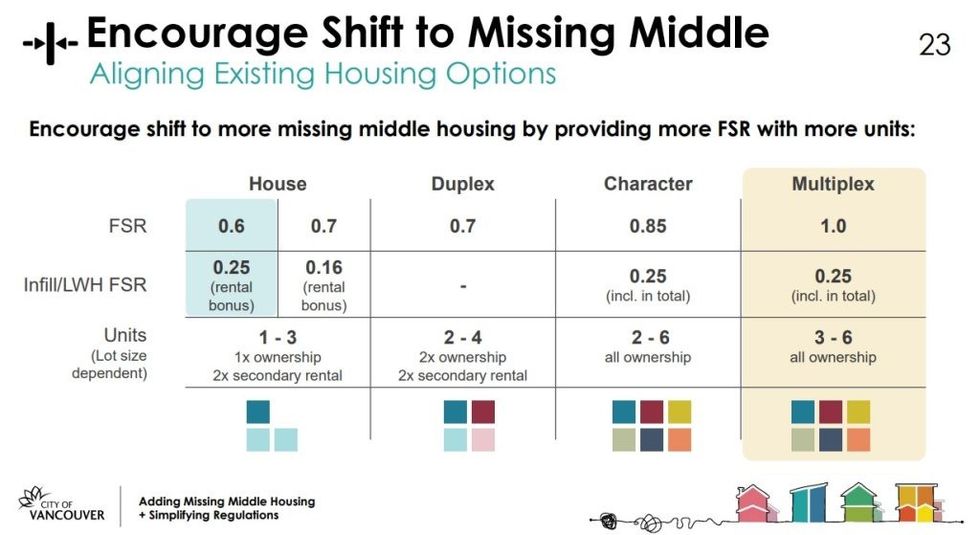

Here, again, the debate is about density, and specifically: the Floor Space Ratio (FSR).

Floor Space Ratio (FSR), Explained

FSR is the number, usually expressed as a decimal, that represents the maximum amount of square footage a property is allowed to be built to, relative to the size of the lot. An FSR of 0.7, for example, means that if a site is 1,000 sq. ft, the maximum size of a house that can be built on the site is 700 sq. ft, which means that the higher the allowable FSR, the higher the density.

In Vancouver, residential zones (RS) allow for FSRs beginning at 0.60, with bonuses and exclusions permitted if certain criteria are met, and higher FSRs are allowed for properties with additional units, such as duplexes, which start with a 0.70 FSR. For a multi-storey building, such as a three-storey walk-up, if the maximum FSR is 1.0, then the maximum floor space of each floor can only be 33% of the size of the site.

This is to say that if more units are allowed on a given site, but the FSR is not high enough, the size of the units will have to be smaller. It's about finding the right balance, and there's good reason to believe that what the City is currently proposing -- the aforementioned FSR of 1.0 -- is not the right balance.

Owen Brady, one of the directors of Abundant Housing Vancouver, a non-profit dedicated to pro-housing education, says the City's proposed plan "misses the mark."

Russil Wvong, who ran for Vancouver City Council with Forward Together in last fall's municipal election, said the 1.0 FSR was "surprising."

Tom Davidoff, Director of the UBC Centre for Urban Economics and Real Estate, called the 1.0 FSR "absurdly low."

Khelsilem, Council Chairperson for the Squamish Nation, described the presented plan as an "unserious proposal for addressing our city's housing needs and creating a better city."

Most of them, and many others, focused on the 1.0 FSR, with many voicing support for an FSR anywhere from 1.2 to 1.5. Even that is modest compared to the 1.5 to 2.0 discussed in a February 2022 paper on upzoning in Metro Vancouver authored by Marc Lee, a Senior Economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives' office in British Columbia.

"Upzoning to missing middle ranges means an increase in the maximum floor space ratio to between 1.5 and 2.0," Lee wrote. Even under that increased FSR, Lee said the site could need to be more efficiently used in order to accommodate more density, such as loosening the building's setbacks from the street or a loosening of building height requirements.

The Right Balance

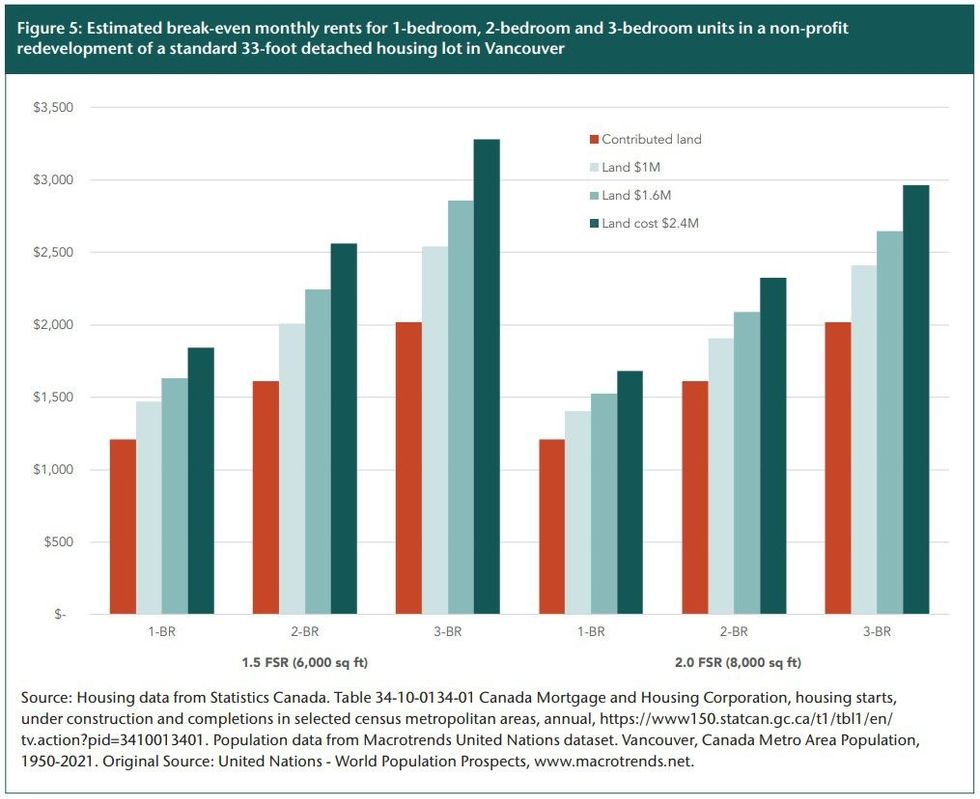

This is all before touching on the financial component, which is again about finding the right balance, this time between land prices, construction costs, and the various fees associated with building housing. The viability of building such housing could also be made more difficult depending on whether it's being provided by a non-profit that just needs to break even, or by for-profit developers.

"At 1.5 FSR, the break-even rent for a one-bedroom unit is $1,209 per month for contributed land, rising to $1,473 per month for property costing $1M, and $1,631 and $1,842 per month for parcels costing $1.6M and $2.4M respectively," Lee says.

However, Lee adds, "at 2.0 FSR, lower break-even rents are possible by spreading the land cost over more units: $1,407 per month for a one-bedroom with land costing $1 million, $1,525 and $1,684 for land costing $1.6 million and $2.4 million respectively."

In short, this is to say that with all things being equal, a higher FSR would do well towards making the housing units more affordable. This isn't to say that FSRs should always be as high as possible, however, as Lee points out that projects with too high of an FSR could risk the building becoming less ground-oriented and require elevators as well as other common building spaces. Again, it's all about finding an ideal balance.

Although many are unsatisfied with the FSR component, others are happier with the second element of the missing middle housing plan, which is focused on simplifying regulations that have held -- and continue to hold -- Vancouver back from more missing middle housing.

RELATED: Lost No More: Victoria Passes Divisive Missing Middle Housing Initiative

The City has said it is exploring changes such as creating consistent building height and setback regulations, eliminating complicated and restrictive design guidelines, and consolidating the City's excessive amount of different zoning districts. (There are currently nine different zoning districts just for single-detached homes and duplexes, as an example.)

From now until the end of the month, the City of Vancouver is hosting a series of information sessions on missing middle housing and the outlined proposal. Information sessions are as follows:

- Saturday, February 11, 2:30-5:30pm, St. James Square Community Centre, Room 120

- Monday, February 13, 5:00-8:00pm, Killarney Seniors Centre, Grand Hall

- Wednesday, February 15, 5:00-7:30pm, Roundhouse Community Centre, Exhibition Hall

- Saturday, February 18, 1:00-3:30 pm, Dunbar Community Centre, Room 208

- Wednesday, February 23, 5:00-8:00pm, Marpole Neighbourhood House, Gathering Hall

- Saturday, February 25, 2:00-4:00pm, Hastings Community Centre, Community Hall

- Monday, February 27, 6:00-7:00pm, Online

In addition, from now until Sunday, March 5, those interested can complete an online survey about the City's proposal.

Following this public engagement period, the proposal will be refined before a second public engagement period in Spring 2023. A final report with the proposed changes will then be presented to council in Fall 2023, followed immediately by a public hearing and final decision, before the changes come into affect, if approved, by the beginning of 2024.