The Bank of Canada continued its policy of quantitative tightening last month, bringing the benchmark rate to a 22-year high of 5%. In part, the bank attributed the move to “surprisingly strong” consumption growth, which came in at 5.8% in the first quarter of the year.

In investigating the drivers of consumption -- both actual and desired -- a new report from Scotiabank Economics cautions that it will still be some time before the BoC can begin to consider rate cuts. More specifically, it says, it’s unlikely that the bank will be in the position to cut until well into 2024.

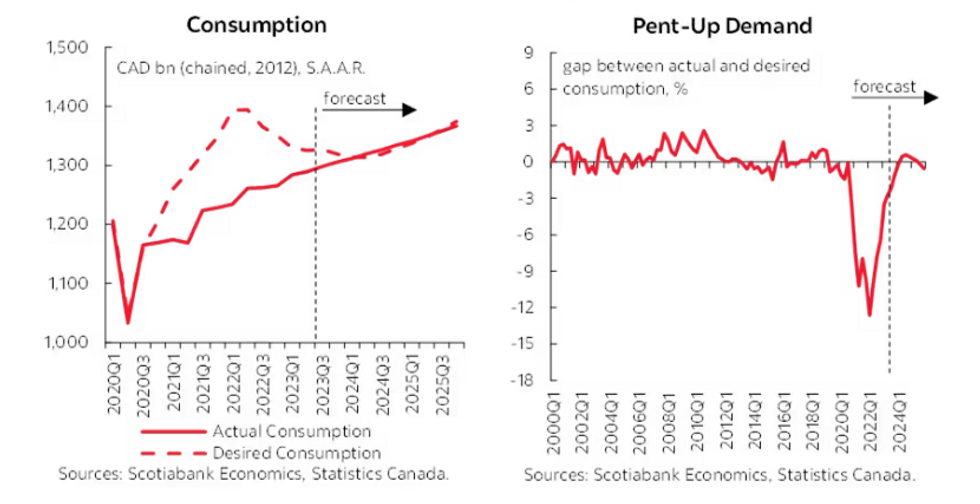

“The Canadian economy has been incredibly resilient in the face of rapidly rising interest rates,” writes René Lalonde, Director, Modelling and Forecasting for Scotiabank. “Much of this surprising strength can be ascribed to pent-up demand -- a measure of the gap between actual and desired consumption -- amongst a broad range of things, including increased wealth and population growth. While all three factors are linked, this note focuses on pent-up demand as a source of economic resilience.”

Lalonde -- who was previously the research director for the BoC, and has also spent some time working on modelling at the International Monetary Fund -- points to the pandemic for some context, saying that it was during that time that the gap between actual and desired consumption widened, leading to a greater degree of demand.

“Low and accommodative interest rates, easy access to credit, strong labour market recovery, and record low unemployment, combined with increased net wealth through rising home equity and excess savings and high oil prices, drove a substantial increase in Canadians’ desired level of consumption,” he says. “On the other hand, supply constraints and public health rules hampered their ability to increase their actual consumption to fulfill the desired level.”

While the BoC’s hike cycle was intended to help to close the gap between actual and desired consumption -- in turn, quelling excess demand -- the gap remains in the negative.

“A more negative gap means more pent-up demand,” explains Lalonde. “This persistence of pent-up demand explains in large part why the economy has been incredibly resilient in the face of many headwinds including tighter monetary policy. As a result, the real policy rate must remain in restrictive territory until pent-up demand and the upward pressure it creates on the output gap and inflation is alleviated.

“We forecast pent-up demand to be eliminated by the second quarter of 2024, largely driven by higher real rates and lower desired consumption as a result. Only then will the BoC be able to start gradually reducing its policy rate without undermining its efforts to tame inflation.”