A group of Ontario developers have signed a pledge to cut the prices of the homes they build, putting their money where their mouth is in an attempt to make a real impact on housing affordability.

The catch: they are asking municipal, provincial governments, and the federal government to reduce or eliminate the various development charges that essentially serve as a tax on housing, adding to the costs of building that developers pass on to buyers.

"For every dollar of tax eliminated by any level of government from the cost of delivering new housing, we will immediately reduce the price of all homes we sell by the amount saved, dollar for dollar," the coalition says.

The group is calling itself the Coalition Against New-Home Taxes (CANT) and includes Republic Developments, Alterra, Altree Developments, Devron, and Forum Asset Management, among many others.

The Coalition

The birth of the coalition can be traced back to January and Republic Developments President & CEO Matt Young.

"It kind of started with myself and a consultant that I work with having a chat early in January," Young tells STOREYS. "We were just kind of talking about the market and what we were seeing and how unaffordable pricing has gotten. We had started doing a bunch of research on why it got so expensive, and I told him that 'You know, taxes have gone up more than any other cost in the proforma of a project.' So, we thought trying to do something to target governments [and get them] to pay attention to those taxes, look at reforms around those taxes, would be an interesting idea."

Young then started reaching out to various homebuilder colleagues, many of them liked the idea, and the ball got rolling from there. Although he declined to identify them, Young says that some developers would not commit to joining the coalition and signing the pledge.

"I think we have an incredible group and since the story has come out, more developers have reached out to me saying they'd love to be a part of the pledge, so we're going to have more and more homebuilders signing on to the pledge, and it sends a message. These are people who are leading the charge. These are people who care about housing affordability. The ones who don't sign the pledge maybe are the ones that care less about that."

As for the idea of the pledge, Young says it was a direct response to the current market environment, where numerous condo projects across the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area are not selling or being put on hold.

"The concept of the pledge came up because we were talking about the fact that I don't think any developer or homebuilder wants to make more money right now," says Young. "I think what they all want to do is build housing and get shovels in the ground. So, we thought this idea of doing a pledge, kind of like the giving pledge, would sort of send the message to the public that we are on their side and we actually do want to build housing that is affordable. But we can only build housing at a price relative to the cost to build, and right now taxes account for 30% of a home, so if you want lower pricing, taxes was the lowest hanging fruit to do that."

The Costs

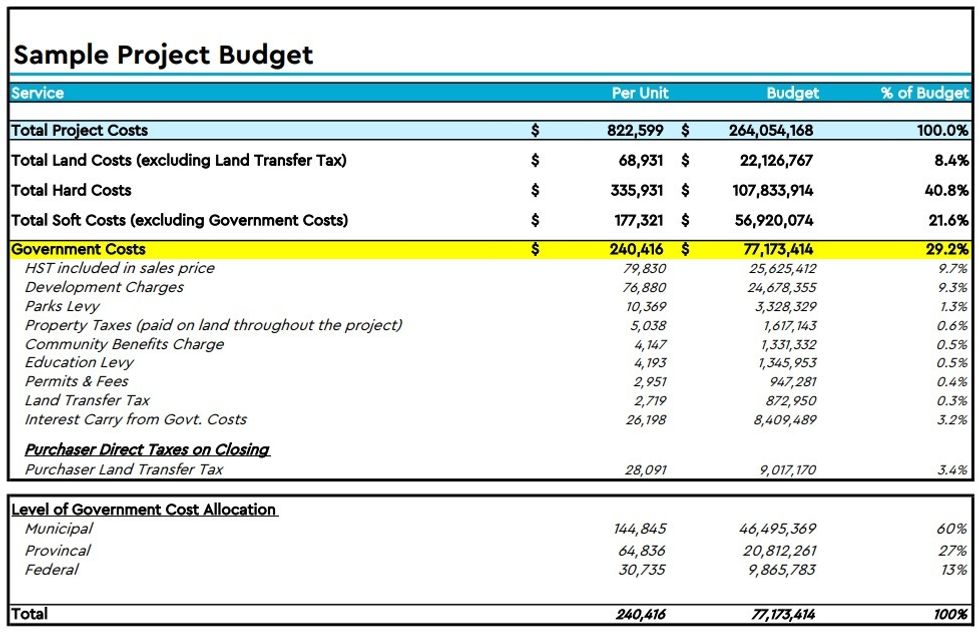

In their pledge letter, dated July 31 and addressed to the heads of three levels of government and others, the coalition included a sample proforma for a hypothetical 321-unit high-rise condo project in a mid-market location in Toronto. According to their provided proforma, this project would have a total cost of $264,054,168.

On a project level, government costs account for $77,173,414 of that total, which represents 29.2% of the total budget. On a per unit basis, government costs account for $240,416 in the price of each home, with the biggest line items coming from the HST and development charges.

"It's actually not just the taxes," adds Young. "We also include in that the interest saved on those taxes, because for a number of these taxes, we actually pay upfront, before the home is completed and closed. And when we pay them upfront, we have to finance those costs, which means we're paying interest on those costs. We're actually including that interest as part of the price that we would reduce."

On the other side of these development charges, however, are the governments, which typically use these charges to fund things like infrastructure. The coalition's letter does not provide a solution to address how governments would be able to make up for this funding gap, saying only that "there are better tools to fund these infrastructure costs which are more sustainable." Young recognizes this, but also points out that not all infrastructure is paid for by governments.

"We, as a builder, if we're building a project in an area that doesn't have sufficient capacity or requires a new road or sewers, we actually have to build those," he points out. "We build them and we pay for them. The development charge is a double dip — it's tax on top of the cost we already have to build. We can't actually use our development charges on the projects [and the new infrastructure that's required]."

Young also points to the concept that's behind this — the concept of "growth paying for growth," a topic that was at the centre of a debate in British Columbia last year after the Metro Vancouver Regional District proposed to raise its development cost charges, which was later pushed through despite a warning from Sean Fraser.

"Everybody always talks about development charges funding infrastructure," he says. "A lot of that infrastructure that gets funded are used by everybody in the city. In Toronto, the number one line item is for transit. That infrastructure benefits everybody in the city, not just the 20,000 to 30,000 new homeowners that buy every year. I think we need to look at how that's funded and everybody needs to pay their fair share, so we're not burdening first-time homebuyers, young people, and new immigrants."

The Ask

In their letter to the various levels of government, CANT is asking for three things. The first is that the government eliminate the HST on all new housing, similar to last year's move to eliminate the GST on new rental construction. "Reforms have been implemented with rental housing and should now be extended to all new ownership housing as well," the coalition says.

The second ask is for governments to eliminate the land transfer taxes on new construction, which buyers pay upon closing. In Toronto, Young points out, there is both a municipal and provincial land transfer tax, and the coalition is asking for the introduction of a one-time credit on these taxes, which would be direct savings for buyers.

Last, but not least, is municipal development charges, which the coalition points out have gone up over 600% since 2009, rising from $36,000 per unit to $240,000 per unit. The coalition is asking the City of Toronto to "reduce development charges on new housing to the inflation adjusted rate based on the starting value of 2009 development charge rates," adding that this would amount to $6,857 for a one-bedroom apartment and $11,033 for a two-bedroom apartment.

Young says that the research they conducted found that eliminating these tax incomes for the various level governments amount to approximately 5% of Toronto's budget, a little over 2% of Ontario's budget, and about 1% of the federal budget.

It's not the first time these issues have been raised, but Young says the coalition is hoping this time will be different and believes the clear-cut pledge can make that difference. Timing is also everything, he says.

"When you're in a really good market, where interest rates are low and demand is really high, then it's really easy for the public or the government to say 'Well, if we cut taxes, you're just going to make more profit.' That's totally valid. But we're in a totally different time right now where nothing is selling and nothing new is being built, so it's the perfect time to do something like this. We're willing to have any accountability measure governments want to implement to ensure savings get passed on, but further than that, there's a financial incentive to ensure savings get passed on, because people can't afford the homes that are available today and if we can lower the prices to the point where they could afford those homes, we would start to see shovels get back in the ground again, we would start to see building happening again, we would start to curb the job losses that are happening in the construction industry, and we can start to increase the supply of housing."

In other words, what the coalition is saving to governments is that the ball is now in their court.

- Bosa Properties Says Burnaby Policies Make Purpose-Built Rental Projects "Unbuildable" ›

- Anthem, Polygon, And Canderel Voice "Deep Concern" Over Burnaby's New ACCs ›

- How BC's New Four-Month Eviction Notice Rule May Affect First-Time Buyers ›

- Forum At Odds With Guelph Over $15.5M Development Charges Bill ›