On a pre-pandemic summer day, the Jack Layton Ferry Terminal is buzzing with people wearing swimsuits, carrying coolers, large umbrellas, towels and bags filled with snacks and sunscreen.

Loading onto the Ongiara Ferry, patrons journey across Lake Ontario to the Toronto Islands western ferry terminal. Once docked, they are welcomed by a very handsome bronze statue sculpted by Emanuel Otto Hahn.

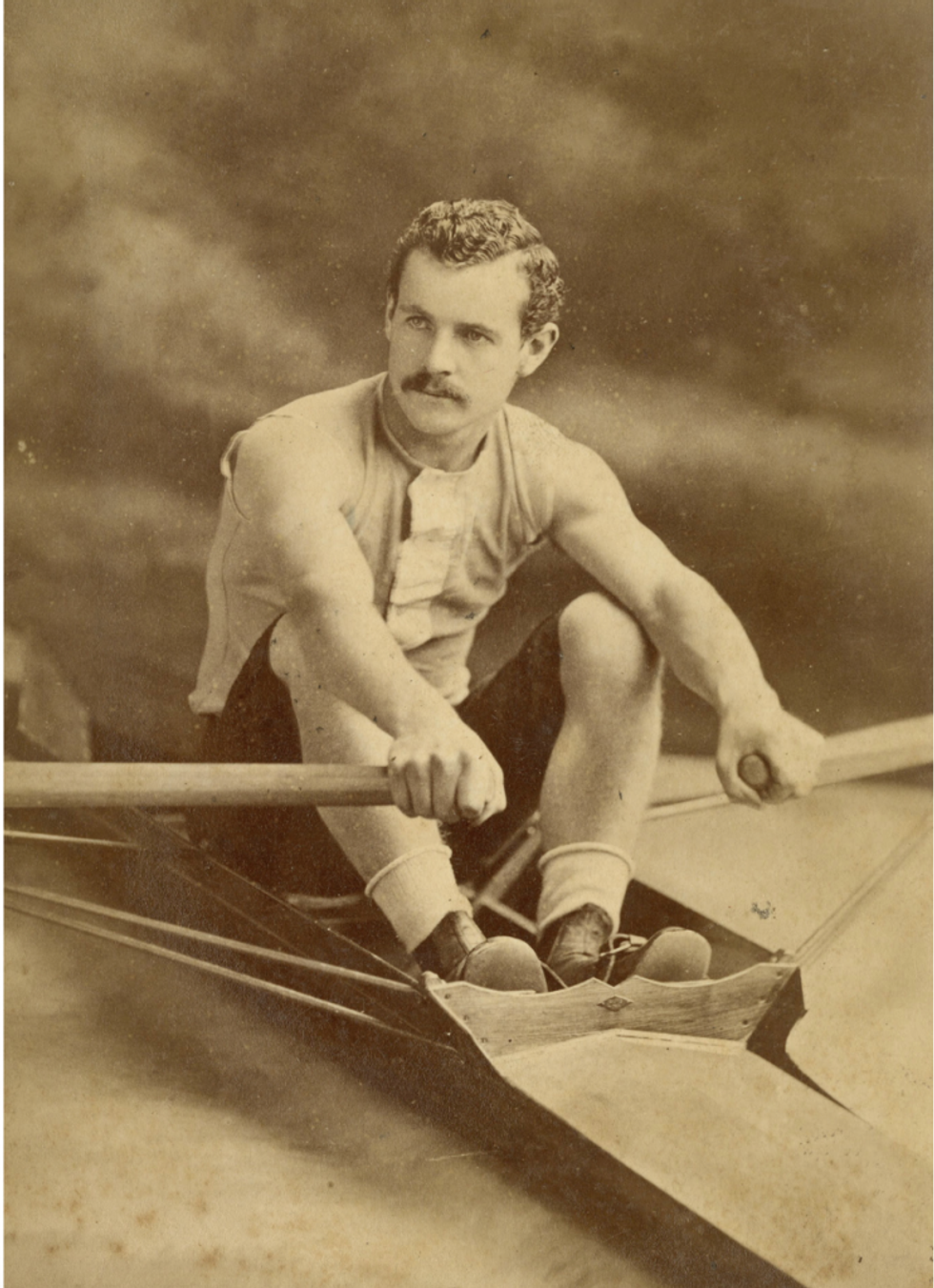

The male figure kneeling on a pedestal has perfect posture, a muscular build, slicked back hair, moustache, trunks and seagull flying behind him. He holds two oars while looking towards mainland Toronto.

The statue was originally located at the Canadian National Exhibition, but was moved to the Toronto Islands in 2004. The relocation was fitting as that portion of the island bears the sculpted figures family name. This is where the story of Canada’s first world champion and greatest oarsmen, Edward “Ned” Hanlan would begin his rise to fame.

From Lake Ontario to the Thames River

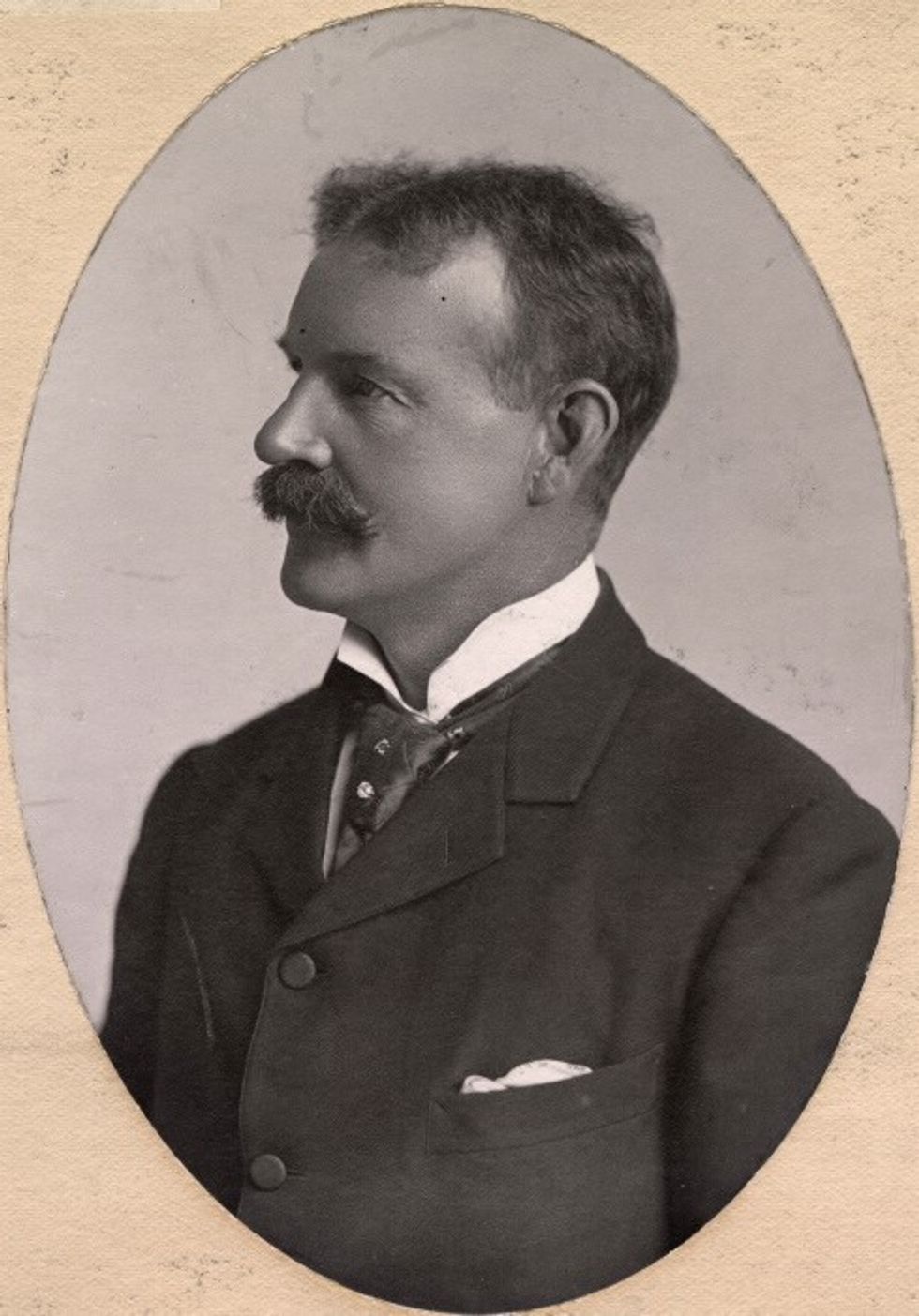

Born in 1855 in Toronto, Edward Hanlan grew up on the Toronto Islands at what is now named Hanlan’s Point (after his family). He was the son of John Hanlan and Mary Gibbs, the first leaseholders on the western part of the islands as well as hotel owners.

Surrounded by water and watching fisherman and rowers, it’s not surprising Hanlan would be inspired to spend most of his time on the lake. He’d row three quarters of a mile daily on a skiff -- a shallow, flat bottomed open boat -- to the mainland to attend school, run errands and meet friends.

In his teens, Hanlan started rowing competitively, entering his first race at 16 years old in a team competition that they would go on to lose. But losing would not go on to be a common thread in Hanlan's life, he reportedly only fewer than a dozen times in his more than two-decade career.

He won the amateur sculling championship of Toronto Bay, his first win in a singles event at 18 years old. He’d continue to win at the local, national and international level. At every race, Hanlan wore a blue shirt and red headband, leading to the nickname “The Boy in Blue.”

READ: Legendary Houses: The City (and Home) that E.J. Lennox Built

With every win his fan base grew. People waited to welcome him home after races, the City of Toronto threw him receptions and marches, fans showered him with gifts, and a poem called Edward Hanlan: An Ode was even written by W.H.C. Kerr.

In 1880, he raced on the Thames River in London, England and with more than 100,000 spectators in attendance, he beat Australian Edward Trickett to become Canada’s first world champion in an individual or singles event. He held that titled until 1884 before losing to William Beach in Sydney.

After racking up 300 wins over his career, Hanlan retired in 1897 and cemented himself as one of Canada’s greatest oarsmen. In his retirement, he became the first head coach of the University of Toronto Rowing Club and eventually an alderman for Toronto from 1898 to 1899. As alderman, he raised issues regarding the waterfront and advocated for bike paths on the islands, bike lanes in the city, and public swimming pools.

The Move to Mainland

Like his father before him, Hanlan became a hotelier. The same year he became a world champion, he got a lease from the City of Toronto for three-acres of land where he erected a Second-Empire style hotel by the architectural firm of William Frederick McCaw and E.J. Lennox. Hanlan sold the hotel in 1892, while some 17 years later in 1909 it would burn down.

When Hanlan, his wife, and their kids moved to the mainland in 1892, a house was waiting for him. The home at 189 Beverley Street had been built as part of the celebrations after his victory in the English Championships.

The semi-detached structure is interesting as similar dwellings have symmetrical facades, but 189 Beverley Street has added decorative elements. While 187 Beverley Street has a flat stone facade with equally stacked windows, Hanlan’s side has a bay window and balcony with decorative trim. Both homes do have similar entranceways with a second-floor balcony covering the porch.

A Stroll Down Beverley Street

Beverley Street runs for about one kilometre from College Street to Queen Street West. Its origin has been debated as some think it was named after Solicitor General Sir John Beverley Robinson, while others believe it was dedicated to former Lieutenant Governor of Ontario the Honourable John Beverley Robinson. The most popular theory is it was named after the grand house the Beverley Robinson family lived in on the southeast corner of Queen Street West and John Street, known as Beverley House.

When Hanlan moved to the street it was lined with stunning mansions, most built in Second-Empire style. Diagonal from him was the George Brown House, originally built for the father of Confederation. Though in 1892, Duncan Coulson, president of the Bank of Toronto, would be Hanlan’s neighbour after taking residence in Brown’s former home.

Other notable residents on the street included wealthy tanner George Lissant Beardmore, whose home is now the Italian Consulate at 136 Beverley Street, and Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King who resided at 147 Beverley Street with his parents while studying at the University of Toronto.

Today, most of the homes are apartments including Hanlan’s. According to a neighbour, the main floor has been vacant for quite some time, which a peek in the main window will confirm, but the second-floor tenants are still around. The street is also now lined with bike lanes, schools, condos, churches, Grange Park and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

An International Legacy

Hanlan died in 1908 at the age of 52 from pneumonia. An estimated 10,000 people paid their respects at St. Andrew’s Church before he was buried at Toronto Necropolis Cemetery.

His impact on Canadian sports was not forgotten. In 1926, the City of Toronto dedicated that statue now on Hanlan’s Point to him and a provincial plaque was placed next to it. There is a tugboat named after him at the Hanlan’s Point Ferry Terminal, as well as pumping stations, roads and the Hanlan Boat Club, which houses the rowing clubs of Upper Canada College, Havergal College, and the University of Toronto.

About 15,000 kilometres away from Hanlan’s Point, is a small town of approximately 5,000 people in New South Wales, Australia called Toronto, named in honour of Hanlan’s birthplace. His legacy is global, which is all the more impressive given his fame took place in a time before social media, the internet, television and even air travel.

He earned his renown the old fashion way: one (world-beating) stroke at a time.

(Lead Image: Edward Hanlan statue at the Canadian National Exhibition, courtesy of Toronto Public Library)