If the turn of the year has inspired you to begin saving for a down payment on a Toronto home, we hope you're cool with waiting 24 years to complete the transaction... because according to recent data, that's how long it will take the "representative" household to save for the "representative" down payment in the city right now.

According to a new report from the National Bank of Canada (NBC), someone saving for a non-condo (semi-detached, freehold, etc.) in Toronto, at a rate of 10%, would need to save for 289 months before they were able to afford a down payment.

This calculation stems from a representative home price of $1,039,438, which is hypothetically being worked towards via an annual household income of $178,499.

Meanwhile, someone with an annual household income of $124,335, who is seeking to buy a condo priced at $615,805, would need to save for 51 months at a rate of 10%.

READ: Trend of Trading City Living for Suburban Space Unlikely to Last: CIBC

At four years and three months, the condo timeframe is much quicker than the 20+ years of a ground-level home, but still -- we'd argue -- they both sting.

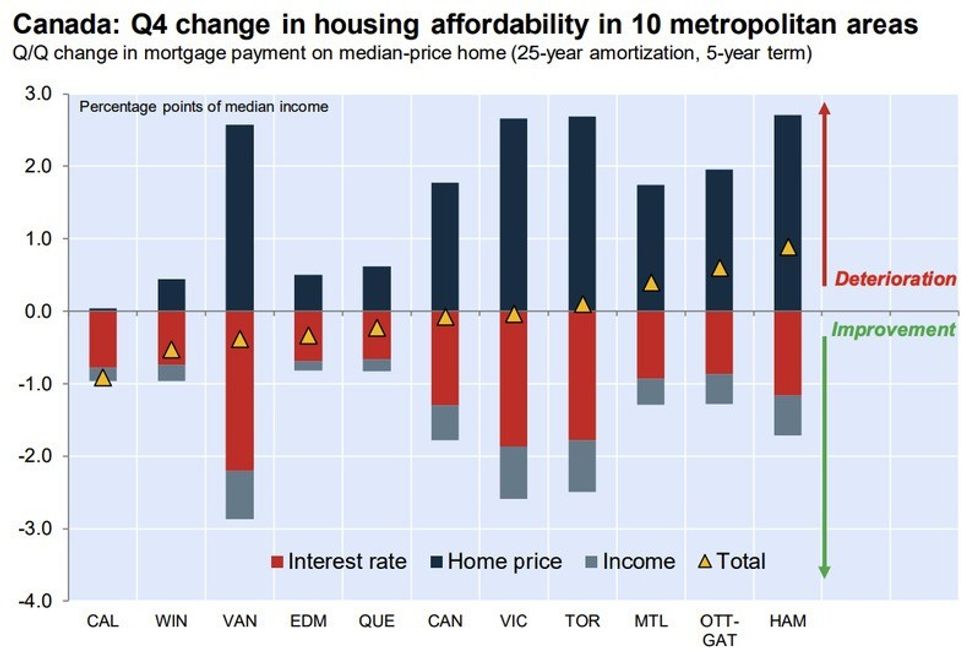

" Housing affordability in Canada improved in the fourth quarter of 2020, marking a third amelioration in a row," says NBC's report. "That said, the improvement this quarter was much less impressive. Higher incomes and record low interest rates were almost completely offset by a substantial rise in home prices."

In Toronto specifically, condos and non-condo dwellings saw their affordability move in opposite directions through Q4 2020. Non-condo homes saw deterioration (the MPPI -- the mortgage payment on a representative home as a percentage of income -- was up 0.4 pp), while condos saw improvement (with MPPI down 1.2 pp).

"This was in line with the urban composite index. The median home price for condos and for non-condo dwellings increased 1.2% and 5.5%, respectively, lifting the median home price for all dwellings combined to nearly one million dollars," the report explains.

"The median annual income increased 1.3% and interest rates declined, but this was not enough to fully offset higher home prices. The median home price for all dwellings combined increased 4.9% over the quarter, outrunning the urban composite index in this regard. Overall, the MPPI* deteriorated 0.1 pp on a quarterly basis, which was worse than the urban composite index, but improved 3.0 pp on an annual basis, which was slightly better."

Country-wide, prices for the national composite saw their highest quarterly gain in 11 years through Q4, elevating 4.5%. Meanwhile, a 29 basis points decline in the 5-year benchmark mortgage rates has helped keep housing affordable, but -- surely -- it's the nearly 100 basis points decline those rates have seen since the start of the pandemic that have most impacted the current appreciation of home prices.

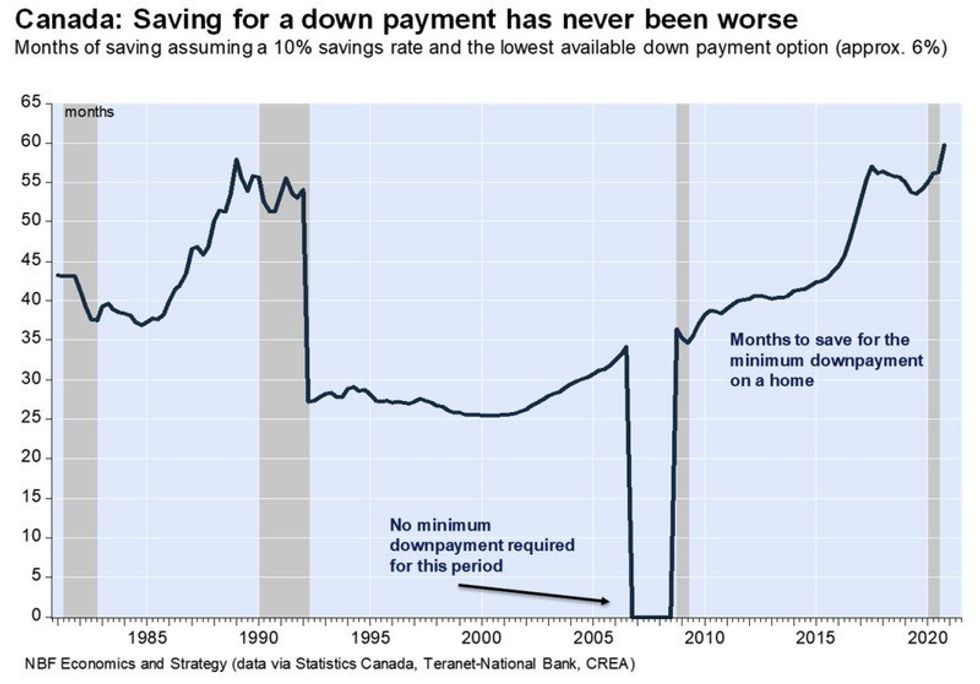

"Although the confluence of all these factors has resulted in home affordability having never been better since 2015, there is another hurdle for potential homebuyers. The rise in home prices has translated into a higher down payment," NBC says. "At a national level, there has never been a worse time to accumulate the minimum down payment."

Assuming the same savings rate of 10% mentioned for Toronto specifically, on a national scale, it would take 60 months -- or five years -- to save for the minimum down payment on the representative home. What's more, as interest rates are unlikely to rise soon, and as vaccine rollout leads a return to more typical market conditions, home prices are expected to keep growing through the coming year.

"As a result, affordability is likely to deteriorate on both a mortgage payment as a percentage of income and down payment basis going forward," NBC says.

As home ownership climbs the unaffordability ladder, it's common for many to turn toward the rental sphere in hopes of some economic relief without the requirement of leaving the city entirely. But this sector faces issues too. Despite rents reaching low lows through 2020 -- a result of folks fleeing Toronto in search of larger pastures -- many of the individuals who, in essence, keep the municipality running aren't actually able to afford living here... even through renting.

In fact, Housing a Generation of Essential Workers 2: Modelling Solutions states that essential workers, who typically earn between $40,000 and $60,000 annually, have been pressured to leave the region since well before COVID-19 showed up. According to the Board of Trade’s Economic Blueprint Institute, there are approximately 330,000 workers in Toronto earning within the range mentioned above; approximately 90,000 of those individuals would be classified as “essential workers.”

While issues of housing have existed for individuals in this earnings range for years, the pandemic has served to highlight the impact these workers have on Toronto’s functioning (and, by association, what it would mean if they weren't in the city at all). The report describes the roles of health-care workers, cooks, custodians and social workers, to name just a few.

Amid concerns about housing affordability in the city -- ownership or otherwise -- solutions continue to be posed. "Missing middle" housing needs begin to be addressed, city staff challenge controversial provincial orders, and, in the midst of crisis, purpose is found for spaces otherwise unused. These answers -- while often imperfect -- speak to a broader awareness of the need for accessibility, and the strength of community support, alive in the city's fabric. It's the details such as these that, while costs climb, serve to remind why any of us wanted to be here in the first place.

But, tender sentiments aside, there's no denying: 24 years to make a down payment in Toronto is a tough pill to swallow.

(And it's one that probably won't go down easy anytime soon, whether you quit your avocado toast habit or not).