An old landmark Kitsilano heritage house has been put on the market, triggering anxiety among heritage advocates who fear that it will go the way of thousands of other character houses in Vancouver, tossed into the landfill -- or renovated to the point of newness, with every trace of original patina lost, a replica of its former self.

The house at 2704 W. 12th Avenue has been in the same family since 1959, and is classified as heritage B, says listing agent Lorne Goldman. However, a heritage designation does not protect a house from demolition. The asking price is $4.999M, a reduction from $5.5M in the four months it’s been on the market. It sits on two 33’ wide city lots, which wasn’t unusual for a big house when it was built in 1914.

Goldman says it’s not known what the City would allow for the property until the new owner applies for redevelopment. In Vancouver, property is typically valuable because of the land, not the building on it. The assessed value of the 4,107 square-foot house is $10,000, while the land is assessed at $4.359M, based on data from last July.

“Most likely they would allow you to take the main house and put two units in there, and then in the back, you might get another detached little house back there. But you will never find out what you get until you make a proper application with the City.”

Although the house has been deemed an important heritage building, it’s not safe from demolition, says Goldman.

“Without question, Heritage B houses have been taken down,” he said. “[The City] can make life difficult for you when you apply to demolish, but ultimately they can’t stop you. They can promote the conservation of the house and engage in negotiation to create more density. They will do that for a period of time before they give you a demo permit.”

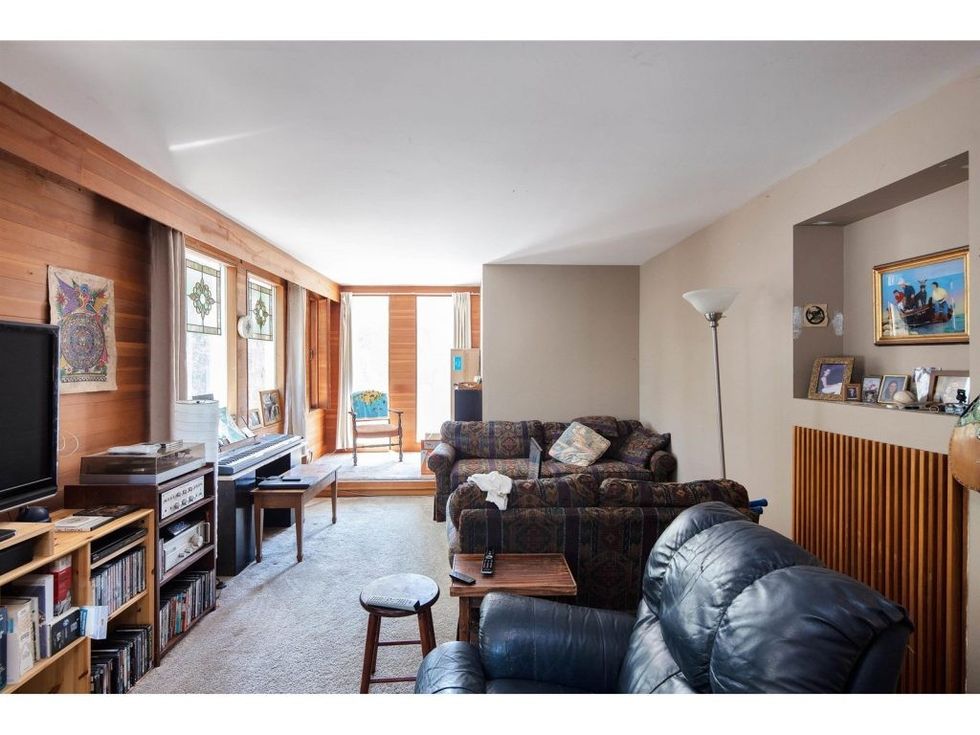

So far the people who’ve viewed the house haven’t talked about outright demolition, he said. Most have talked about redeveloping it in some way. Renovation is less likely, he says, because much of the interior has been extensively altered over the years, although there’s a wraparound front porch, stonework, stained glass windows, and original stained in the foyer. It’s not a grand example of pristine heritage, but it’s one of the largest remaining old houses in Kitsilano, says Goldman.

“It’s of note. Certainly there are not many left in Kits.”

Heritage consultant Don Luxton said the house was built at a time when the economy had just collapsed. It was common to buy two lots and use one for a garden, he says. The first owner, perhaps a speculator, only lived in it for a couple of years.

“This is the last gasp of prosperity at the time,” says Luxton. “The economy completely collapsed. As we know, Kitsilano, after the war, you couldn’t give these big houses away, so they got broken up into rooming houses, and three or four families would live in them. You could buy one of these big houses on a big lot for really cheap. The neighbourhood shifted away from single family.

“It’s clearly an important house, on the B list. A great house and it’s readily recognizable.

“It’s in a prime location, ripe for redevelopment, and it needs investment obviously. Should it be preserved? I would say yes, and this is an example of how we want to keep our neighbourhood character. So, what is the city going to offer?”

Planner and vice chair of the Vancouver Heritage Foundation, Stephen Mikicich, said a sensitive makeover that includes infill housing could easily be done without destroying the house’s character. It could become a model of “missing middle” density, which is what the neighbourhood is already known for. Much of Kitsilano’s detached housing stock had been carved up into suites over the decades, making it one of the more affordable neighbourhoods in the city, even though it’s on the pricey west side. Mikicich said he was not speaking on behalf of the heritage foundation, but rather expressing his own views.

His concern is that instead of protecting the house, the City might allow much higher density that would see the house demolished, or, at the other extreme, expensive duplex units built. Instead, he’d like to see it preserved as missing middle housing.

“Up until a few years ago there were efforts to incentivize the retention of heritage and character to allow densification and infill as an economic incentive to retain the history of these communities. That all went out with bathwater with the last council and the Broadway Plan and Vancouver Plan,” he says, referencing two major planning documents that will transform the city with significant density.

“There is no longer any incentive to do that [retention],” he says. “The Vancouver Plan is really a plan for displacement and clear-cutting the entire city. Here’s this lovely home, the neighbourhood landmark, stood there proudly for 110 years. It has never really been an exclusive single family home. For years it operated as a rooming house for elderly women.

“I look at all the great examples in Kits, where they stratified, in-filled, and created wonderful housing without destroying everything.

“I think with the floor area and modifications to the existing house, you could easily do three, if not four units in the main house and replicate something like that in the backyard.”

City staff recently announced a proposal to allow up to six units on any residential lot, as an effort to increase “missing middle” density, which is part of the Vancouver Plan. Missing middle is townhouses, rowhouses, and duplexes, of which the city is in short supply. The proposal includes allowing more height and much more floor space in order to incentivize the building of multi-unit homes. The City is also looking at downsizing the allowable square footage for a detached house, in order to disincentivize the building of that housing type. The property is 66’ wide, which could easily accommodate six units of housing, possibly more. The viability of preserving the house would be up in the air.

“One of the things that’s clear is that the plan does not place any value on established neighbourhoods or communities, nor built heritage,” says Mikicich. “It completely disincentivizes retention of these buildings because people will think, ‘why bother saving it because I can get the same [result] for tearing it down?’ That’s really the conundrum.”

Luxton said the city incentivizes the preservation of heritage by offering extra square footage in exchange. And Kitsilano zoning already encourages retention of character homes. The neighbourhood is filled with big houses that have been converted to multi-unit homes.

“The problem is, there is so much pressure for density and it’s on an arterial and other policies apply, so someone could scoop it up for upzoning. It’s ripe for redevelopment, is the problem.

“There are lots of opportunities to save the building,” he adds.

The house is solidly built out of quality materials, so it doesn’t make sense to throw it into the landfill, he says.

“I would argue this is an excellent example of where a heritage revitalization agreement could be used to creatively infill on the double lots and find some way to conserve the house. And it’s already on the register, so that opens up something of a pathway.”