Housing affordability is one of the biggest crises of our time and not everybody agrees on the solutions. Some argue that developers who are granted permission to build high-density projects should in turn provide a portion of that new housing at rates most people can afford. Developers often respond saying those requirements hold back the construction of new housing and that ensuring affordability is a responsibility that lies more so with government.

The reality is this: approximately 95% of all new housing in Canada is constructed by the private sector and about 95% of the new housing they construct is provided at market rates, according to recent data published by the CMHC.

Market rates reflect the going rates that can be achieved at the given time. Times change, however, and while that usually means market rates will go up, it also means some homes will gradually become more affordable, through what's known as "filtering."

In a research report published in June 2024 that examined the topic, the CMHC defined "filtering" as "the gradual transition of housing units from higher-income households to lower-income households over time."

Vacancy Chains

Filtering generally occurs in two ways, with the first being through vacancy chains, which occurs when a household moves up to more expensive housing, freeing up their less expensive home. This then starts a chain reaction, as a household that moves into that freed up home is likely also freeing up an even less expensive home.

Specifically as it impacts filtering through vacancy chains, the CMHC concluded that exclusively building low-cost housing "isn't optimal."

"Doing so primarily benefits low-income households, but decreases the welfare of high-income households as local wages can decline and lower property-tax revenue leads to less amenities," they said. "That results in many families with post-secondary education leaving the area, which leads to a further decline in amenities. In this case, only few low-income households move to better homes."

Building only high-cost housing also isn't optimal, as it "improves amenities but doesn't improve affordability or the welfare of low-income households very much."

"The study finds that building mid-cost or a balanced mix of low-, mid- and high- cost housing is the best strategy," CMHC concluded. "This is because it makes homes more affordable and benefits most household types. Moreover, building these unit types reduces the likelihood of low-income families leaving their city."

Depreciation

Having the value of something decline is usually not desired, but it can be a positive if you're a renter looking for a home you can afford, as rents start declining shortly after construction is completed, as a building gets older and older.

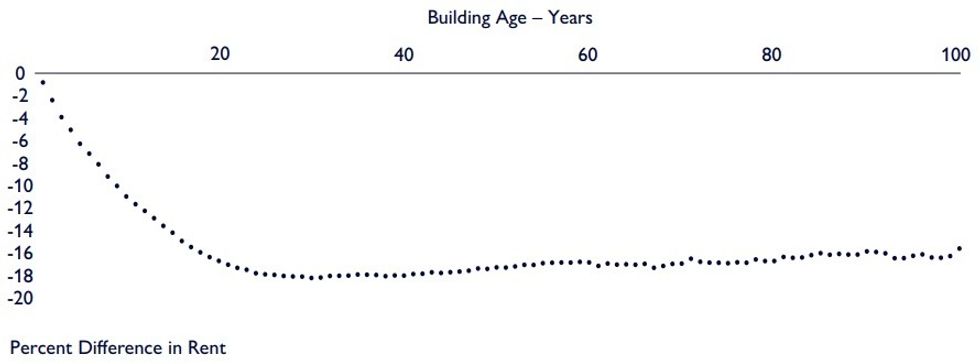

According to their research, rents fall by 5% within four years and steadily decline by up to 20% after approximately 20 years, before then flattening out.

"While it is true that rent levels have increased over time in Canada, this model accounts for both the overall inflation rate, and neighbourhood market trends," the report notes. "Therefore, these findings can be thought of as profiling rents of existing buildings relative to a new building, all while holding fixed the natural upward trend in rent across time."

The research also found a distinction between buildings / jurisdictions with rent control and those without.

"Regions with rent control saw a faster and deeper decline in average real rents; rents fell to almost 25% below the rent level in a new building after 30 years. In comparison, regions without rent control tend to see their rents decline more slowly and bottom out at close to 20% below those of a new building after around 40 years. In provinces with rent control, the relative depreciation of real rents through the lifecycle of a building may be more pronounced because of limitations on a property owner's ability to increase rents on incumbent tenants, an effect that doesn't operate when a building is initially leased. This may reduce, for example, the property owner's incentive to invest in the property and therefore lead to lower rents."

Filtering

In late-February, the CMHC published an article looking at construction timelines and concluded that multi-family projects initially take about three to five years to design and get approved. They then take around one to two years to construct, meaning multi-family projects take a total of seven to eight years to move from conception through to reality.

Add in the time it takes for filtering to reach its endpoint and you get the answer to the question of how long it takes a newly-proposed market-rate housing unit to become affordable.

"All-in-all, from design of a project to filtering that makes housing attainable, it takes 25 to 30 years before new housing supply is delivered and its full impact on lower rents or prices is felt," the CMHC said.

This largely explains why little to no effect on affordability is immediately seen when new housing enters the market — a stance sometimes taken by those who argue that supply is not the problem or solution.

As to what can be done to facilitate filtering, the CMHC concludes that building housing across the spectrum of affordability is the best strategy. Furthermore, the "continuous construction of new housing" is also crucial, as more new units create more opportunities for filtering to occur and a steady flow of new units allow for a steady amount of filtering.

The CMHC notes that it is reasonable to ask why building more affordable or social housing to begin with isn't the best solution, as that would in theory cut out the 20 to 25 years it takes for housing to naturally filter.

In response, they point out that the average amount of social housing as a proportion of all housing stock among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries is 7%. To meet this benchmark, Canada would need an additional 575,000 units, which is still only a fraction of the oft-cited 3.5 million new homes that we need. In other words, it would help, but it shouldn't be the solution that we rely on, particularly since these projects often also face financial barriers.

In short, the CMHC believes that facilitating filtering by creating new supply of all affordability levels is a better strategy (but not the only one). As the headline of their article notes, "Solving the housing crisis is a marathon not a sprint."