A Toronto-based architectural firm has big ideas for the future of the Prince Edward Viaduct, better known as the Bloor Viaduct.

Drawing inspiration from New York’s High Line and London’s Camden Highline, Farrow Architects’ vision for a reimagined bridge involves extending the current sidewalk into the existing roadway to create a vibrant pedestrian-centric space.

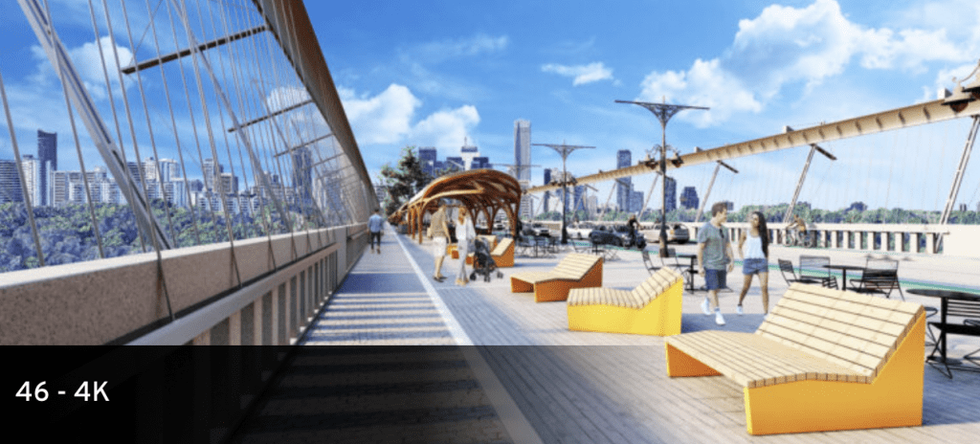

‘Market Bridge’ would include market stalls, public art, seating, bicycle racks, and flora. According to Farrow Architects, the vision involves “a generous new pedestrian realm for the city, that could mix public space, plazas with public art, and socially driven market stalls housed in mixed use market-like pavilions.”

The space would become an elevated home to events, community gathering pavilions, musical performances, and arts interventions -- complete with the backdrop of the Don Valley, Lake Ontario, the city skyline, and beyond.

Farrow Architects paints a colourful picture of a one-of-a-kind retail incubator, filled with a variety of multicultural themed gourmet food stalls, high quality local produce and foods, handmade chocolates, artisan bakers, sustainably and ethically sourced coffee, locally grown flower stalls, and Ontario-produced fruit and vegetables.

In other words, it’s your perfect Sunday morning all in one spot. Further helping the weekend-in-the-city cause, the reimagined space would connect to the network of Don Valley trails below thanks to new stairs and an elevator system.

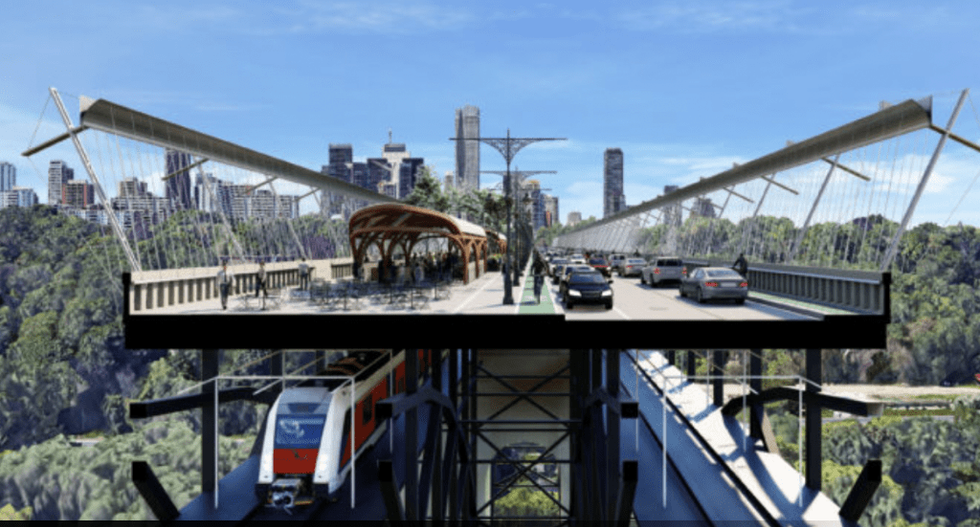

The road section of the viaduct would be reconfigured to a profile that contains three lanes of traffic -- one of which will be for parking during off peak-traffic times -- two bike lanes, and a pedestrian precinct that is close to half the width of the viaduct. Currently, the bridge houses five lanes of traffic, flanked by bike lanes and a sidewalk.

With the plan, the automobile clearly takes a backseat, with car traffic reduced significantly in each direction. In a city plagued by traffic and congestion in non-pandemic times, this idea will undoubtedly meet pushback from drivers who use the busy bridge to travel between the city’s east end and the downtown core. Passionate city residents have already taken to social media to share their distaste for the project.

But proponents of the idea say it's time to start to finally put people before cars in Toronto the way they do in many other cities around the world. “Creating more places for people with a people-first and not car-first design is exactly what Toronto desperately needs,” says Naama Blonder, an architect and urban planner at Smart Density. "It’s exactly these types of initiatives that may seem ridiculous to some -- like CafeTO may have pre-pandemic -- that we need more of."

Blonder praises Toronto's pandemic-inspired CafeTO program, which permits restaurants to expand their patios onto the street, as an example of the city finally beginning to reach its potential. "I pray it's here to stay," she says. Other recent examples of a shift away from the car include initiatives to turn city parking lots into parks and vibrant public spaces.

City columnist Matt Elliott says that the state of the Bloor Viaduct represents a disconnect from progressive planning initiatives on surrounding city streets.

"Right now, the Viaduct is kind of the forgotten middle child. Bloor Street to the west has gotten bike lanes -- among the most-used in the city -- and Danforth to the east has received a hell of a makeover with the Destination Danforth patios and bike lanes," says Elliott. "In between, the roadway suddenly gets hostile and unpleasant to all non-car road users. Closing the gap so Bloor-Danforth can be a more consistent pedestrian-friendly corridor seems like an no-brainer to me."

In a tweet in response to one Elliott posted sharing of Farrow Architects' plan, Counsellor Mike Layton addressed the state of the Bloor Viaduct. "Transportation wrote staff are actively working on a plan to make it safer for cyclists and pedestrians. There is significant construction happening on the bridge in coming years to barrier then to surface. A chance for something safer and more fun."

But, in terms of Farrow Architects' ambitious vision, are there better spots to put a pedestrian-focused public space initiative than on the bridge, given the high volume of cars that cross it each day? “It’s not like taking the Gardiner and transforming that,” says Blonder. "The bridge isn't even that high-traffic." Driving her point home (no pun intended), she points to the fact that the project isn't proposing to do away with the car completely.

Transit advocate Steve Munro – who has lived beside the Bloor Viaduct for 40 years – says the plan’s claim is that one lane each way would match the capacity of Bloor and Danforth is not quite true.

“Traffic funnels from the east onto the bridge from Broadview, not just from Danforth. Similarly, from the west, traffic comes north on various streets east of the narrower section to the west and accumulates from Church to Parliament,” says Munro. “In other words, at neither end is it a case of a single lane inbound feeding onto the bridge, but of multiple approaches contributing to the demand. This is particularly an issue given that the next bridge to the south is at Gerrard and to the north at Eglinton, with some capacity provided by the Mortimer/Pottery/Moore link.”

Munro also points to the fact that traffic backs up well across the bridge when the DVP is closed. “It becomes the favoured route out to Broadview and thence (via O’Connor) to the further north reaches of the DVP,” he says. He adds that the bridge should not be congested any time the subway closes, as it becomes a major transit link.

"Congestion is always a concern and I’ve got no doubt the transportation division would track travel times closely after any change, but the city has found time and time again that these kinds of street makeovers can happen with travel time delays for cars that amount to, at most, a few minutes on average, and the trade-offs are often worth it," says Elliott.

For Monroe, his concerns span further than traffic considerations. “I cannot help wondering if the proponents have ever walked across the bridge either in the depth of winter or high summer. There is no escape from the elements there,” he says. "I can assure you that in a storm, or even the occasional high wind (and we get them here), anything that is not nailed down will not stay put and the idea that the space could be used for cafes or shops is rather comical.”

On the design front, Munro questions the need for a parking lane, the plan’s “cavalier dismissal of the luminous veil as if somehow it would be ok for it not to be there” (referring to the bridge’s barriers to prevent suicides), and the concept of an elevator, which he calls “not thought through.”

As for Farrow Architects, the company points to the environmental, social, cultural, and economic gains offered by infrastructure reuse projects. At very least, the proposed plan -- or any revamp, really -- would be a lot easier on the eyes than the current five lanes of boring traffic.