Eviction is a "widespread" risk for any British Columbian who rents, regardless of where you live and how much money you make, a recent report from the BC Eviction Mapping Project found.

The project is being undertaken by First United Church — founded in 1885 and now provides essential services in the Downtown Eastside — with funding from the City of Vancouver and Government of Canada. It seeks to gather information regarding evictions with the goal of improving tenant protections across BC.

This week, First United published BC's Eviction Crisis: Evidence, Impacts and Solutions for Justice, a report detailing the findings of the British Columbia Eviction Survey conducted between June 2022 and September 2023.

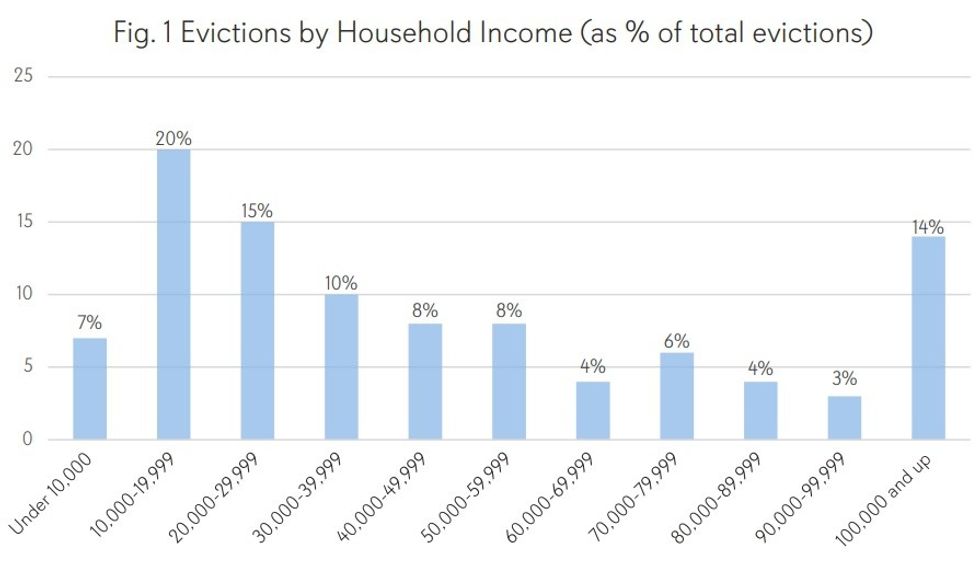

"Eviction is a risk for people across the income spectrum in British Columbia," said First United in the report. "When we designed this study, we asked respondents for their household income and used $100,000+ as the highest specified category because we did not expect to see evictions for households above this income."

Out of 698 respondents, all of whom have experienced eviction, 14% reported a household income of over $100,000, which was the third-highest demographic after those with a household income between $10,000 and $19,999 (20%) and those with a household income between $20,000 and $29,999 (15%).

The report does not suggest that households with an income of over $100,000 face a higher risk of eviction, only that evictions are a problem that can affect anyone regardless of income level.

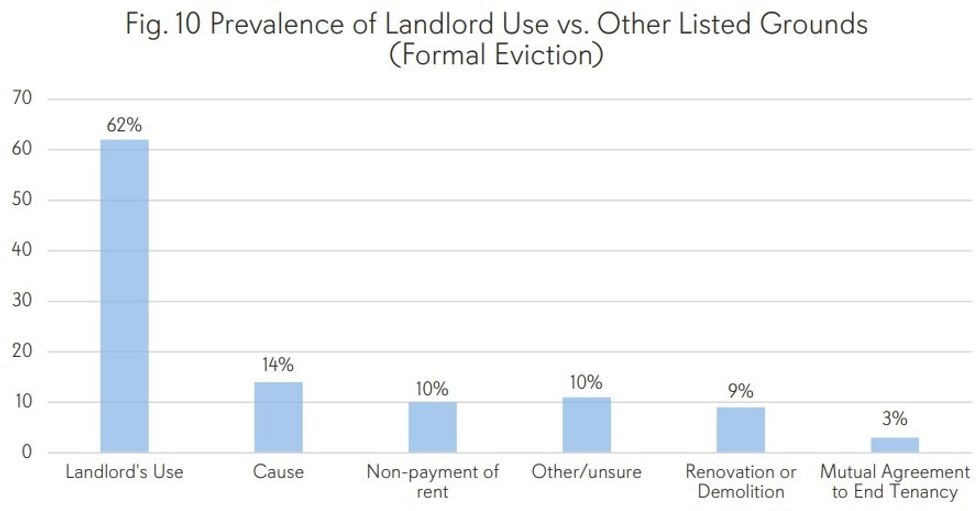

Survey responses also indicate that non-payment of rent is not the main reason for evictions. Of the 698 respondents, just 10% of those who have been evicted say they were evicted due to non-payment of rent. The most common grounds for eviction, accounting for 62% of the 698 evictions, was by far "landlord's use."

This finding aligns with research conducted by the University of British Columbia, who concluded earlier this year that BC remains the "eviction capital of Canada" as a result of a high number of no-fault evictions, which includes personal use by the landlord.

The problem with "landlord's use" evictions, First United says, is that landlords do not need to provide any proof to evict tenants on these grounds. Tenants who are evicted this way only have 15 days to make a dispute claim with the Residential Tenancy Branch, or else their eviction is treated as accepted in the eyes of the law.

First United points to the surge of "renovictions" — evictions on the grounds that the landlord wanted to renovate the unit — that BC saw over half a decade ago, which was largely curtailed after the Province changed the laws to require landlords to provide evidence — a change First United believes can also quell the "landlord's use" problem.

Regardless of how tenants were evicted, displacement — defined as being forced to leave the neighbourhood they were living in — was about equally as likely for tenants of all income levels, with rates ranging from 73% to 86% for those with household incomes between $10,000 and $99,999.

Those with incomes over $100,000 saw the least amount of displacement (62%) while those with incomes under $10,000 saw the highest amount of displacement (92%) and also faced the highest risk of homelessness (46%). For Indigenous tenants, the risk of displacement and homelessness were then even higher, First United found.

Many of these no-fault evictions are occuring because of a lack of vacancy controls that would prevent landlords from greatly increasing rent between tenancies, First United's report suggests.

Of the 698 survey respondents, 30% of those who were evicted due to "landlord's use" faced a rent increase at their next tenancy of between $500 and $1,000, and 17.5% faced a rent increase of over $1,000.

"The higher rent increases we see in those evicted for 'landlord's use' may represent a trend of tenants being forced to move from rent-controlled existing tenancies to much higher market rent in situations where landlords were strongly motivated to evict, due to the lower rents of those tenants and the rapidly escalating rental market, which provides an obvious opportunity for increased profit," First United says.

The other way of looking at this, First United says, is that long-term tenants are essentially being punished because they pay lower rents as a result of restrictions on annual rent increases, which increases the likelihood that landlords will seek to hike rents and resort to evictions to do so.

"On top of the obvious financial consequences, long-term tenants are also especially vulnerable to the harms of displacement from their communities because they are likely to have deep relationships to their communities through social ties, services, work, school, and other critical links," says First United.

To fix the aforementioned issues, and many others, First United is recommending a suite of changes to the Residential Tenancy Act, the first of which is to require that landlords provide evidence before being able to evict a tenant on the grounds of "landlord's use."

Other recommendations include improving procedural fairness and appeal rights regarding Residential Tenancy Branch hearings, increasing penalties for landlords who resort to illegal conduct such as a harassment or coercion, implementing vacancy control, and banning pet restrictions and cooling equipment restrictions.

First United says it Eviction Mapping project remains ongoing, with data and its interactive map updated monthly.